Even before the Nazis seized power in Germany in 1933, they had placed their tanks on the battlefield of the imagination. “Event culture” with darker undertones was in full swing. A heady mixture of pagan-inspired rituals, firework displays launched on river boats and rallies with folk music was the nationalist answer to the freewheeling modernism of the Weimar Republic.

Moritz Follmer is a heterodox scholar, who applies a sharp cultural lens to metropolitan life, politics and individual strivings and pastimes as the backdrop to disaster falling on Germany. The cultural offerings of national socialism, he believes, held such mesmerizing appeal for so many Germans precisely because it commanded a range of tastes from middle-class conservatism to emerging mass culture — a combination that “mobilized vast energies” across the population by appealing to fustian sorts and neophytes alike.

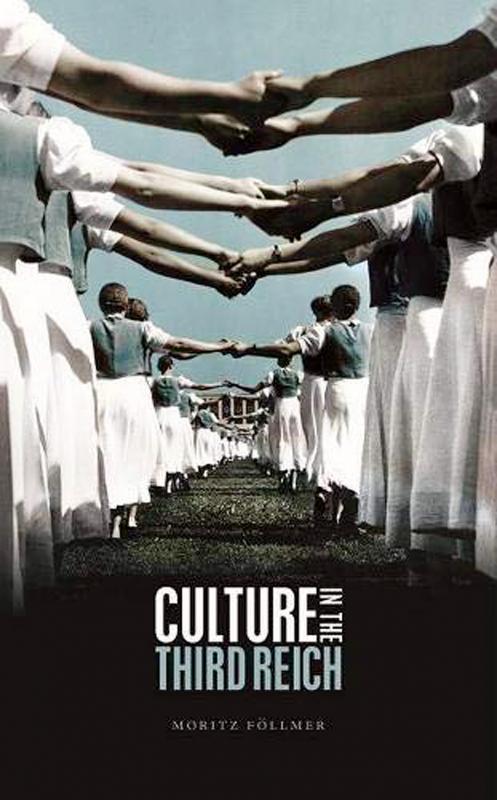

Culture in the Third Reich explores the multiple ways in which popular diversions — from magazines to concerts and cinema to beauty parades — helped power German fascism. Diaries and letters bring texture to a chronological narrative.

We meet Elisabeth Gersleben von Alten in the dying days of the Weimar. In her reflections on attending Brecht and Weill’s collaboration The Threepenny Opera, summing up its cast of misfits and waspish socialist message as a “glorification of criminality,” she exemplifies the fruitful cultural soil among an educated but parochial bourgeoisie into which the rising National Socialist party could plant its seed. By contrast, Gersleben writes to her daughter in praise of Wagner.

“Can anything so beautiful really exist? How stupid not to enjoy it more often and let everyday concerns make us forget the intellectual riches of our German nation,” she says

By 1932, though, the “event culture” of the movement was about more than paeans to dead composers. It was, Follmer reminds us, a vast outpouring of innovation and energy: thoroughly modern Nazis.

Leaps in cinematic technology exploited emerging trends and the thrills of mass culture while claiming to represent the eternal flame of Germanic endeavor. It was a fine time to be a moderately prosperous, culturally active German — as long as you didn’t fall on the wrong side of the political divide, increasingly tightly drawn as the Fuhrer solidified his power. Goebbels, as minister of propaganda, oversaw a vast expansion in subsidy for films and theater, often appointing himself as de facto director to productions on a whim, evoking the spirit of Mel Brooks’s The Producers: “Film meeting. Cromwell material ready in outline,” Goebbels wrote. “Will be really good. My idea.”

Images of healthy holidaymakers in relaxed garb graced the pages of magazines.

“Dictatorial interventions,” the author observes, “existed alongside bourgeois institutions and modern rends.”

Goebbels’s desire to increase respect for German culture abroad brought him into conflict with the foot soldiers of cultural slog at home and a tetchy standoff with the Gauleiter (regional party leader) of Saxony.

“If he had his way there,” the minister observed tartly, “there would be no more German theater, only volkisch pageants, open-air performances, myth and all that nonsense.”

By the mid-1930s, a “utopian dimension” was consciously added to the mix, along with the punitive force of repression. Follmer sees All Quiet on the Western Front, Erich Maria Remarque’s pacifist saga, as the moment culture becomes an outright weapon. At the premiere, stink bombs and mice were let loose by Nazi supporters to drive out the audience. Not long after, intimidation, arrest and violence were meted out to dissenters. The anarchist and writer Erich Muhsam was forced to act as a dog in politically targeted vaudeville and drink dirty water in front of mocking audiences.

The power of narrative gives rise to toxic fakery — all stories must end the way the authorities deem they should. When Muhsam refused prompts to commit suicide or face reprisals, prison wardens beat him to death and claimed he had taken his own life.

The Reich, Follmer observes, became a Gesamtkunstwerk (cultural synthesis) — a phrase usually used for the full-spectrum dominance of Wagner’s great operas. This brings us to the book’s slight flaws.

Cultural studies is a jargon-prone field and, at times, the translation grinds awkwardly through the gears. “Culture is the beautiful surface appearance of the Third Reich” is one of too many sentences whose meaning we can intuit, but doesn’t move happily across the language divide.

We proceed inexorably from culture as national “show” to its role in purveying the dreary doctrine of racial purity and preparing the road to militarism and conflict. Zarah Leander’s starring role in Die grosse Liebe (The Great Love), a girl meets Luftwaffe love story of heroic sacrifice on the eastern front, was seen by 28 million cinemagoers when it was released in 1942. The war machine demanded a different, more testing propaganda to the days of national spectacles — but the show rolled on.

What happens after the collapse of 1945 is dealt with fleetingly. The great breach in German culture continued in bitter arguments about those who had accommodated or practiced resistance among the scions of rival groups of emigres, conflicts of conscience that persisted well into my time in East and West Germany in the 1990s.

A postwar application of “cancel culture” meant that artistic sympathizers were effectively binned from official public memory on the questionable assumption that bad art equals bad politics. Younger Germans are probably unaware of the vast appeal of Leander, or the sculptor Arno Breker , who crafted monumental public works to please the Fuhrer, but who still enjoys a quiet following among collectors of his private world (and not just of a dodgy ideological drift).

No single account can ever explain entirely why Germany adopted Hitler as fervently and disastrously as it did. But Culture in the Third Reich goes a long way to explaining how the “glittering surface of the Third Reich” played such a heady part in a deadly mix.

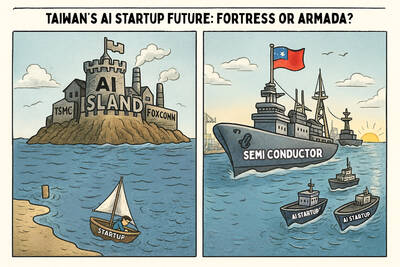

President William Lai (賴清德) has championed Taiwan as an “AI Island” — an artificial intelligence (AI) hub powering the global tech economy. But without major shifts in talent, funding and strategic direction, this vision risks becoming a static fortress: indispensable, yet immobile and vulnerable. It’s time to reframe Taiwan’s ambition. Time to move from a resource-rich AI island to an AI Armada. Why change metaphors? Because choosing the right metaphor shapes both understanding and strategy. The “AI Island” frames our national ambition as a static fortress that, while valuable, is still vulnerable and reactive. Shifting our metaphor to an “AI Armada”

When Taiwan was battered by storms this summer, the only crumb of comfort I could take was knowing that some advice I’d drafted several weeks earlier had been correct. Regarding the Southern Cross-Island Highway (南橫公路), a spectacular high-elevation route connecting Taiwan’s southwest with the country’s southeast, I’d written: “The precarious existence of this road cannot be overstated; those hoping to drive or ride all the way across should have a backup plan.” As this article was going to press, the middle section of the highway, between Meishankou (梅山口) in Kaohsiung and Siangyang (向陽) in Taitung County, was still closed to outsiders

The older you get, and the more obsessed with your health, the more it feels as if life comes down to numbers: how many more years you can expect; your lean body mass; your percentage of visceral fat; how dense your bones are; how many kilos you can squat; how long you can deadhang; how often you still do it; your levels of LDL and HDL cholesterol; your resting heart rate; your overnight blood oxygen level; how quickly you can run; how many steps you do in a day; how many hours you sleep; how fast you are shrinking; how

“‘Medicine and civilization’ were two of the main themes that the Japanese colonial government repeatedly used to persuade Taiwanese to accept colonization,” wrote academic Liu Shi-yung (劉士永) in a chapter on public health under the Japanese. The new government led by Goto Shimpei viewed Taiwan and the Taiwanese as unsanitary, sources of infection and disease, in need of a civilized hand. Taiwan’s location in the tropics was emphasized, making it an exotic site distant from Japan, requiring the introduction of modern ideas of governance and disease control. The Japanese made great progress in battling disease. Malaria was reduced. Dengue was