Beyond the well-deserved praise heaped on Lee Teng-hui (李登輝) as Taiwan’s father of democracy lies another tale, of the dedicated men and women without whom democratization could never have occurred. This is the story of one of them, Jay Loo (盧主義), also known as Li Thian-hok. The book is both a personal memoir and a history of the democratization process with whom Loo’s life has been so closely intertwined.

Born in Tainan in 1932 as one of six children to the poor and devoutly Presbyterian parents to whom he dedicates the book, Loo went to school during the Japanese occupation and delighted in reading Japanese novels, though realizing that Taiwanese were not regarded as equals by their colonial masters.

Loo entered the Presbyterian Missionary High School in 1945, the year the defeated Japanese left. He was astonished to find that lectures were given in Hoklo (more commonly known as Taiwanese). Later, however, Mandarin was imposed and Loo discovered that another group of overlords, Chiang Kai-shek’s (蔣介石) Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), had arrived from China to replace the first.

With the help of Presbyterian mentors, he became one of the last of the students able to study abroad without first serving in the military, and received a scholarship to Macalester College in Minnesota. Later transferring to the University of Minnesota, Loo proved to be a polymath, mastering calculus, pre-med studies and English literature while washing dishes and, during the summer, working as a field hand to make ends meet.

Meeting for political discussions with other young Taiwanese, Loo became convinced that, in order to evolve into a free and democratic nation, Taiwan must become independent of Chinese rule, whether the KMT or People’s Republic of China (PRC). The students formed the 3F — Formosans’ Free Formosa — in 1956, with Loo somehow finding the time to draft a petition to the UN. Not surprisingly, it was rebuffed by UN General Secretary Dag Hammarskjold. Loo gave up his medical studies in favor of political science and economics, taking six to seven courses each semester to meet the requirements and again washing dishes.

Not only did Loo graduate summa cum laude, but his senior thesis was chosen best in the university — an incredible honor at an institution that graduates 10,000 students a year. It’s all the more remarkable considering his native language was not English. Loo also won a fellowship to study at Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School.

Encouraged to submit his senior thesis to the prestigious journal Foreign Affairs, where it appeared in April 1958 under the title “The China Impasse: A Formosan View.” This is an honor that most political science professors can only dream of. Others who appeared in the same issue included former US secretaries of state Dean Acheson and Henry Kissinger, and several international luminaries. Loo was only 25.

Turning his attention to job hunting, Loo found a position as an actuarial clerk where his ability to master complex mathematical tables turned into a lifetime profession. Later, he would begin his own highly successful actuarial practice. He continued his political writing, liaising with prominent figures in the nascent Taiwanese liberation movement such as Thomas Liao (廖文毅), and meeting and courting his wife, Helen, also from Tainan.

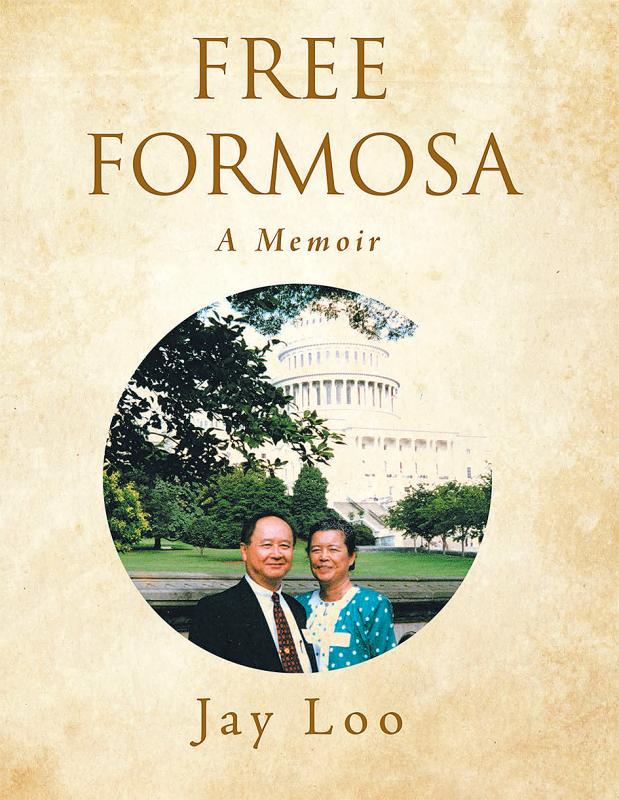

Together the couple became active participants in organizations such as the Formosan Association for Public Affairs (FAPA) and WUFI-USA (the American branch of the World United Formosans for Independence). As such, they lobbied congress to promote passage of resolutions and bills to support Taiwan while cultivating friendships with prominent congressional aides with ties to influential administration figures. These aides can then serve as conduits for messages to high officials.

Together, Jay and Helen attended briefings and conferences relevant to Taiwan at major think tanks such as the American Enterprise Institute, Heritage Foundation and Hudson Institute in Washington and the Foreign Policy Research Institute in Philadelphia. Jay also continues to advocate Taiwan’s cause in magazines, journals and books, of which this book is number two in a trilogy.

With their two sons successfully launched on careers of their own and now retired from their respective professions, the couple continue to participate actively in lobbying for Taiwan and have taken up a variety of hobbies ranging from gardening and water aerobics to target shooting.

As he looks back on the more than half a century of his life in the US, Loo is gratified that there is now a consensus among concerned Taiwanese Americans that Taiwan needs to preserve its democracy and independence from China. Within Taiwan, there has also been a remarkable rise in the perception of Taiwanese identity. Yet Taiwan’s status as a de facto independent nation is increasingly at risk.

Whether military threats and psychological warfare from China, domestic subversion from the KMT and People’s First Party, the pro-PRC media and business interests or, most perilous of all, the Democratic Progressive Party’s lack of a clear vision for Taiwan’s future and consequent inability to implement policy measures that will safeguard Taiwan’s freedom over the long term.

In concluding, Loo vows that, whatever the future holds, he and his wife will continue the work of grassroots diplomacy in trying to help Taiwan preserve its freedom. Though never becoming household names or attaining the status of a Lee Teng-hui, it is through the efforts of Loo and others like him that Taiwan has been able to democratize and to maintain its separate existence. This beautifully written memoir will give readers a sense of what this process was like, and the importance of continuing Loo’s work.

June Teufel Dreyer is a political science professor at the University of Miami, senior fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute and a former commissioner of the United States Economic and Security Review Commission.

This is the year that the demographic crisis will begin to impact people’s lives. This will create pressures on treatment and hiring of foreigners. Regardless of whatever technological breakthroughs happen, the real value will come from digesting and productively applying existing technologies in new and creative ways. INTRODUCING BASIC SERVICES BREAKDOWNS At some point soon, we will begin to witness a breakdown in basic services. Initially, it will be limited and sporadic, but the frequency and newsworthiness of the incidents will only continue to accelerate dramatically in the coming years. Here in central Taiwan, many basic services are severely understaffed, and

Jan. 5 to Jan. 11 Of the more than 3,000km of sugar railway that once criss-crossed central and southern Taiwan, just 16.1km remain in operation today. By the time Dafydd Fell began photographing the network in earnest in 1994, it was already well past its heyday. The system had been significantly cut back, leaving behind abandoned stations, rusting rolling stock and crumbling facilities. This reduction continued during the five years of his documentation, adding urgency to his task. As passenger services had already ceased by then, Fell had to wait for the sugarcane harvest season each year, which typically ran from

It is a soulful folk song, filled with feeling and history: A love-stricken young man tells God about his hopes and dreams of happiness. Generations of Uighurs, the Turkic ethnic minority in China’s Xinjiang region, have played it at parties and weddings. But today, if they download it, play it or share it online, they risk ending up in prison. Besh pede, a popular Uighur folk ballad, is among dozens of Uighur-language songs that have been deemed “problematic” by Xinjiang authorities, according to a recording of a meeting held by police and other local officials in the historic city of Kashgar in

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) was out in force in the Taiwan Strait this week, threatening Taiwan with live-fire exercises, aircraft incursions and tedious claims to ownership. The reaction to the PRC’s blockade and decapitation strike exercises offer numerous lessons, if only we are willing to be taught. Reading the commentary on PRC behavior is like reading Bible interpretation across a range of Christian denominations: the text is recast to mean what the interpreter wants it to mean. Many PRC believers contended that the drills, obviously scheduled in advance, were aimed at the recent arms offer to Taiwan by the