On Nov. 25, 1948 Life magazine telegrammed photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson with an assignment: spend two weeks in China documenting the dying days of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) rule. He stayed 10 months, photographing the impact the civil war had on its populace.

Much is already known about the events leading up to and including Cartier-Bresson’s journey to China: that 18 months earlier he had co-founded photography cooperative Magnum; that he was developing an aesthetic that blends high art and reportage; that the photos he took in the cities he visited — Beijing, Shanghai, Nanjing and Hangzhou — and published in Paris Match and Life, among other magazines, heralded this new visual style — one later dubbed “the decisive moment.”

The decisive moment refers to spontaneously capturing an ephemeral event, with the resulting image representing the essence of the event in question. Placed in the context of the Chinese Civil War, it takes on added resonance: being in the right place at the right time when world historical events are unfolding.

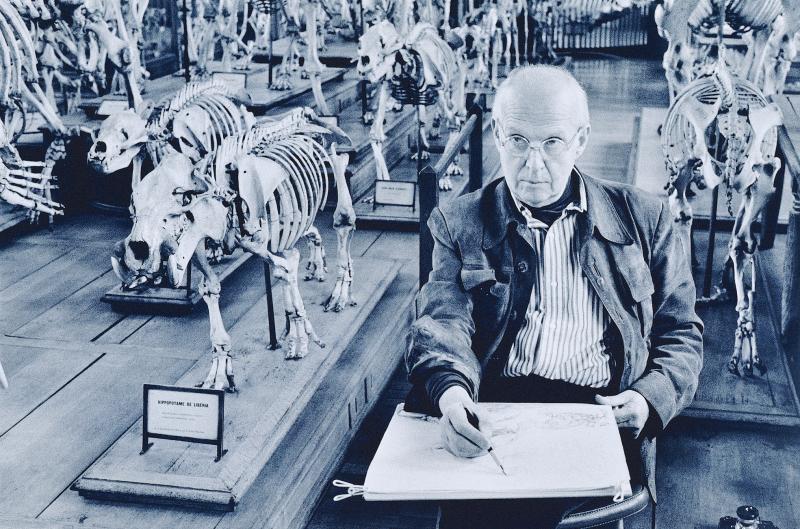

Photo Courtesy of Martine Franck

The Taipei Fine Arts Museum is currently holding an outstanding exhibition of Cartier-Bresson’s photographs from two China trips. The show takes up the museum’s entire third floor and includes 170 images, the majority from his first sortie into the dying days of the Chinese Civil War, and a number from a return visit he made in 1958 as the Great Leap Forward was getting into full swing.

The exhibition, as well as the massive two-kilogram book that accompanies it, is clearly a labor of love for Michel Frizof and Su Ying-lung (蘇盈龍), the two curators who put it together. In addition to the framed photos, the exhibition also displays many of the original magazine stories, in vitrines and hung on the walls, where the original stories appeared, giving the attentive visitor an idea of the ways in which the KMT and communists were portrayed by the Western publications that commissioned the photos and stories they were printed with.

PICTURES OF PEOPLE

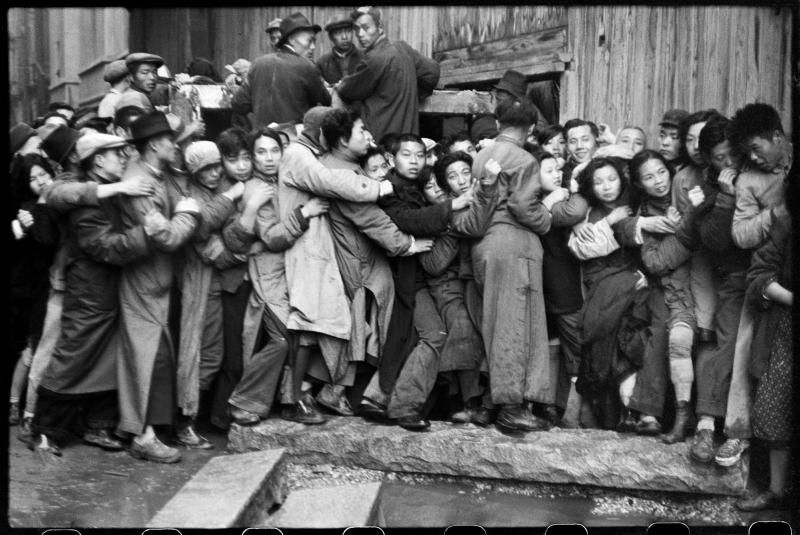

Photo Courtesy of Henri Cartier-Bresson

Upon entering the first section on Beijing, what strikes the viewer immediately is Cartier-Bresson’s humanity — a humanity displayed in the subjects he chose to shoot. He didn’t document the wealthy and powerful, the warlords or the fleeing foreigners, but those most impacted by the civil war: the beggars and street vendors, pilgrims and children — lots of children.

Poverty is omnipresent. In Beijing, we see a beggar with child sitting outside a Muslim restaurant bearing a sign that says her husband is dead; a blind man in Hangzhou begs Buddhist pilgrims for alms as he holds a leash that is affixed to the child that serves as his guide; a small boy in Shanghai pulls a legless man on a cart with tiny wheels.

There is a powerful pathos to these images. The beggar in Hangzhou sitting in front of a window display for wedding dresses his face cast downward, the artificial expression of the mannikin looking off in the distance poignantly underscores the social disparities; a mother anxiously searching for her son while dozens of sitting KMT soldiers look on, their mothers undoubtedly anxiously waiting for news of them.

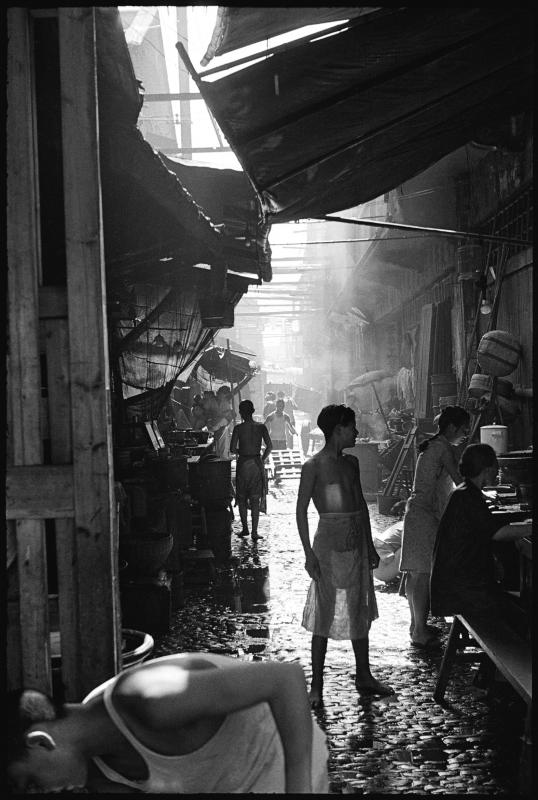

Photo Courtesy of Henri Cartier-Bresson

Although he largely avoided the famous and powerful here, Cartier-Bresson was clearly fascinated by the geometry of Beijing’s monumental architecture and used it to good effect when framing his subjects. In one, a blind fortune teller walks toward the camera and our eyes are drawn to his thin figure framed by two equilateral triangles of shadow cast off a high brick wall. In another, we see a man walking through the Forbidden City dressed in a long dark cape and wearing a white face mask, the pagodas in the background shrouded in fog.

THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC

It’s difficult not to walk away from the civil war pictures and not lament the ineptitude of the KMT government, which Cartier-Bresson considered a “gangster” regime. And although there are plenty of exuberant images — the father in Hangzhou who helps his excited son climb onto a massive statue of Budai (布袋), the fat laughing Buddha — his sympathies are clearly with the communists.

Photo Courtesy of Henri Cartier-Bresson

During the 1930s, Cartier-Bresson, even though he came from a wealthy family, was a known communist sympathizer and, Frizot told me, remained so. If the KMT-era photos document poverty and war, the photos from 1958 suggest a country confidently looking towards the future.

These images were commissioned for the 10th anniversary of the People’s Republic of China. Whereas he was largely free to move around KMT-controlled China, Cartier-Bresson’s itinerary was highly restricted when he returned 10 years later — often confined to Potemkin-like construction projects.

Despite these limitations, Cartier-Bresson traveled 12,000km throughout the country with a guide and documented momentous changes — the construction of a university swimming pool by students using rudimentary tools; the construction of a dam by thousands of workers; villagers smelting pig iron in makeshift furnaces — all done without machines.

Unlike the KMT-era photos, where there would commonly be one or two subjects in the frame, these CCP-era photos focus on groups: children walking single file in front of a propaganda poster or dancing in unison in a Beijing square. Harmony and hard work are the order of the day.

Given what we know today of the Great Leap Forward, it is difficult to walk away from this section thinking that, like many others sympathetic to the Mao regime, Cartier-Bresson was duped by his hosts. It’s an issue the curators address in the short exhibition catalog for the Taipei show where they write that the images “were essential in the Cold War era, and in the Communist and anti-colonialist movements, however they posed a number of legitimate, but unresolved questions.”

Those questions, of course, have largely been answered with the passing of time and looking at these pictures today we see an idealized version of a reality that was slowly coming into focus. Still, there is no question that Cartier-Bresson did, as the curators write, capture “the recurrent exploitation of collective, manual labor.”

One walks out of the engrossing Henri Cartier-Bresson: China, 1948-1949 / 1958 entranced by the French master’s ability to poetically capture life of regular people during a massive upheaval and exhausted by the sheer volume of photos on display. Thankfully it runs until November, so there is plenty of time to visit and revisit the works on display.

Following the shock complete failure of all the recall votes against Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers on July 26, pan-blue supporters and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) were giddy with victory. A notable exception was KMT Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫), who knew better. At a press conference on July 29, he bowed deeply in gratitude to the voters and said the recalls were “not about which party won or lost, but were a great victory for the Taiwanese voters.” The entire recall process was a disaster for both the KMT and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). The only bright spot for

As last month dawned, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was in a good position. The recall campaigns had strong momentum, polling showed many Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers at risk of recall and even the KMT was bracing for losing seats while facing a tsunami of voter fraud investigations. Polling pointed to some of the recalls being a lock for victory. Though in most districts the majority was against recalling their lawmaker, among voters “definitely” planning to vote, there were double-digit margins in favor of recall in at least five districts, with three districts near or above 20 percent in

From Godzilla’s fiery atomic breath to post-apocalyptic anime and harrowing depictions of radiation sickness, the influence of the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki runs deep in Japanese popular culture. In the 80 years since the World War II attacks, stories of destruction and mutation have been fused with fears around natural disasters and, more recently, the Fukushima crisis. Classic manga and anime series Astro Boy is called “Mighty Atom” in Japanese, while city-leveling explosions loom large in other titles such as Akira, Neon Genesis Evangelion and Attack on Titan. “Living through tremendous pain” and overcoming trauma is a recurrent theme in Japan’s

The great number of islands that make up the Penghu archipelago make it a fascinating place to come back and explore again and again. On your next trip to Penghu, why not get off the beaten path and explore a lesser-traveled outlying island? Jibei Island (吉貝嶼) in Baisha Township (白沙鄉) is a popular destination for its long white sand beach and water activities. However, three other permanently inhabited islands in the township put a unique spin on the traditional Penghu charm, making them great destinations for the curious tourist: Yuanbeiyu (員貝嶼), Niaoyu (鳥嶼) and Dacangyu (大倉嶼). YUANBEIYU Citou Wharf (岐頭碼頭) connects the mainland