June 1 to June 7

In February 1988, Robert Wu (吳清友) set aside NT$17.5 million to purchase two Henry Moore sculptures from London’s Marlborough Gallery. He never bought the pieces. Feeling slighted that the gallery manager initially looked down on him as a Taiwanese, he decided that night to use the money to open his own art space back home.

“Without selling any art, that money could support the gallery for four years. If I feature one artist per month, that provides a stage for at least 100 artists,” Wu said in the book Eslite Time (誠品時光) by Lin Ching-yi (林靜宜). The businessman had many friends in Taiwan’s art scene, and knew how hard it was for them to shine internationally.

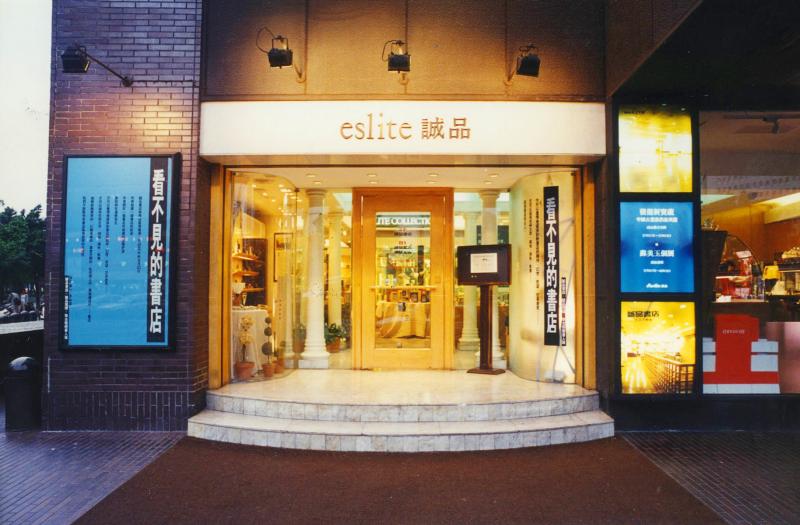

Photo courtesy of Eslite

“I felt that Taiwan was lacking in the arts and humanities,” Wu continued. “Businessmen always meet at hostess clubs or hotels, while ordinary citizens have few places to visit besides movie theaters or parks.”

Despite unexpectedly striking gold in Taiwan’s surging real estate market and becoming a billionaire by the age of 35, Wu remained unfulfilled. Several months after returning home from London, Wu was diagnosed with Marfan’s syndrome and almost died during surgery. After recovery, he knew what he needed to do. On March 12, 1989, Eslite’s Dunnan store opened its doors with a concert by the Taipei String Quartet.

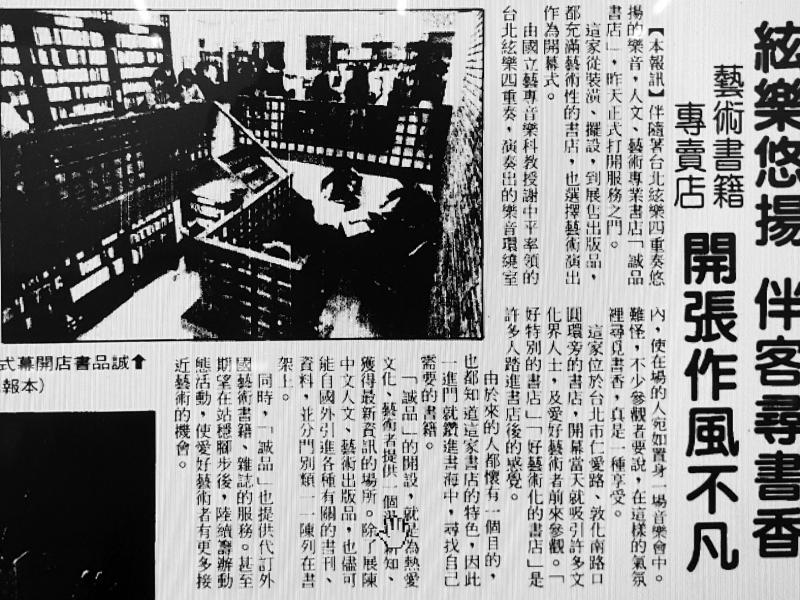

“The store’s decor, displays and products are all highly artistic, and naturally, it chose an artistic performance for its opening,” reported the Minsheng Daily (民生報), one of the few media outlets to cover the event.

Photo courtesy of Eslite

Eslite Dunnan moved to its current location in 1995 and became the world’s first 24-hour-bookstore in 1999. It closes its doors for good today, with the Xinyi location carrying on the mantle of Taiwan’s “sleepless bookstore.”

FIRST INCARNATION

It was a good time for Taiwanese to make money back in the 1980s as the nation’s economic miracle continued to surge.

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

Born in a small fishing village in Tainan, Wu headed to Taipei to seek his fortune. He first found work as a teacher, and later became a star salesperson for a kitchen supply company. When his employer relocated to China, a 31-year-old Wu purchased the company at a discounted price. He renamed the firm Chengjian (誠建) — which shares the first character of Eslite’s Chinese name, chengpin (誠品). It means “honesty,” a value Wu’s father often emphasized as the family’s fortunes rose and fell.

The business took off, and Wu suddenly found himself at the forefront of Taiwan’s real estate boom. He was once so poor that his first employer let him sleep in the office until he received his first paycheck; now he owned two apartments and could afford to buy any art he desired.

He began preparing to launch Eslite shortly after he returned home from London, and the concept morphed from a gallery into a multi-purpose bookstore with a coffee shop, shopping area and cultural events. Even though an investor backed out after his surgery, Wu resolved to push through.

He originally planned to call the store “Elite,” but the name was already registered. Lin writes that “Eslite,” the Old French-language version of the same word, was discovered by an employee leafing through a dictionary to find an alternate name.

The very first incarnation of Eslite had its books in the basement, with a tea house, garden and high-end international artisan brands and vendors on the first and second floors. Eslite Gallery opened two months later in what was originally the building’s swimming pool. The shops were later diversified with stationery and other more affordable crafts.

BROWSERS WELCOME

Taiwan had just emerged from 38 years of martial law, when the government exercised strict censorship over the cultural sphere, and the people were hungry for new ideas as political and social movements surged. Meanwhile in June 1989, Taiwan’s stock market surged to 10,000 points for the first time. If Wu was thinking about money, he would have put his cash into stocks rather than a bookstore.

Before the 1980s, the concept of a bookstore as a commercial cultural space was unheard of in Taiwan. Most of them were small, stuffy spaces stacked to the ceiling with tomes that did not welcome people to linger. Pioneering chains such as Kingstone (金石堂) and Senseio (新學友) had transformed the idea of a bookstore by enhancing the space and visiting experience, but Eslite took things a step further.

On June 30, the Minsheng Daily reported on the “novel concept” of setting aside spaces in the store for the customers to read, relax and hang out — even if they didn’t buy anything.

“Eslite doesn’t reject customers who visit just to browse the books and products,” the article stated. “As long as they appreciate art and culture, they’re all welcome to come here and learn more.”

However, Eslite didn’t turn a profit until its 15th year in business. In a speech to National Taiwan University’s College of Management, Wu reportedly joked: “From the angle of business management, I have completely failed. I don’t really deserve to speak here today.”

The store was immensely popular and expanded quickly to 39 locations by 2000, but the biggest change was making the Dunnan location 24 hours. Eslite Dunnan first experimented with the idea in 1995 as a farewell bash to the original location, keeping it open for 18 hours straight starting from the morning of Sept. 23.

Over 30,000 customers flocked to the store to enjoy the non-stop modern and traditional performances as well as the flea market. It was probably the first time in Taiwan’s history that people had to queue up to get into a bookstore at 4am.

During the move to the current location, Eslite asked customers to fill out a “your ideal bookstore” survey, and many respondents reminisced fondly over the 18-hour event.

“Can there be a bookstore that never closes?” read one response. On its 10th anniversary in March 1999, Eslite responded to the customer’s wishes, and the rest is history.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

On a harsh winter afternoon last month, 2,000 protesters marched and chanted slogans such as “CCP out” and “Korea for Koreans” in Seoul’s popular Gangnam District. Participants — mostly students — wore caps printed with the Chinese characters for “exterminate communism” (滅共) and held banners reading “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party” (天滅中共). During the march, Park Jun-young, the leader of the protest organizer “Free University,” a conservative youth movement, who was on a hunger strike, collapsed after delivering a speech in sub-zero temperatures and was later hospitalized. Several protesters shaved their heads at the end of the demonstration. A

Every now and then, even hardcore hikers like to sleep in, leave the heavy gear at home and just enjoy a relaxed half-day stroll in the mountains: no cold, no steep uphills, no pressure to walk a certain distance in a day. In the winter, the mild climate and lower elevations of the forests in Taiwan’s far south offer a number of easy escapes like this. A prime example is the river above Mudan Reservoir (牡丹水庫): with shallow water, gentle current, abundant wildlife and a complete lack of tourists, this walk is accessible to nearly everyone but still feels quite remote.

In August of 1949 American journalist Darrell Berrigan toured occupied Formosa and on Aug. 13 published “Should We Grab Formosa?” in the Saturday Evening Post. Berrigan, cataloguing the numerous horrors of corruption and looting the occupying Republic of China (ROC) was inflicting on the locals, advocated outright annexation of Taiwan by the US. He contended the islanders would welcome that. Berrigan also observed that the islanders were planning another revolt, and wrote of their “island nationalism.” The US position on Taiwan was well known there, and islanders, he said, had told him of US official statements that Taiwan had not