Early humans were present in Europe at least 46,000 years ago, according to new research on remains found in Bulgaria, meaning that they overlapped with Neanderthals for far longer than previously thought.

Researchers say jewelery and tools found at a cave in Bulgaria called Bacho Kiro reveal that early humans and Neanderthals were present at the same time in Europe for several thousand years, giving them ample time for biological and cultural interaction.

“Our work in Bacho Kiro shows there is a time overlap of maybe 8,000 years between the arrival of the first wave of modern humans in eastern Europe and the final extinction of Neanderthals in the far west of Europe,” said Prof Jean-Jacques Hublin, from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, co-author of the research, adding that that is far longer than previously thought. Neanderthals were roaming Europe until about 40,000 years ago.

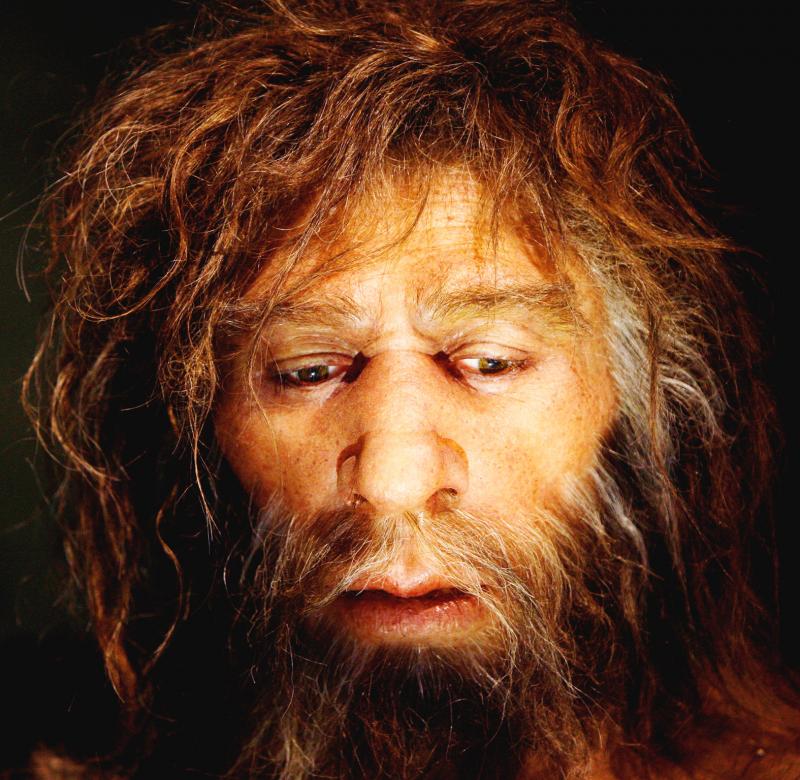

Photo: REUTERS

“It gives a lot of time for these groups to interact biologically and also culturally and behaviorally,” Hublin added.

Writing in studies published in the journals Nature and Nature Ecology & Evolution, Hublin and colleagues report how they excavated Bacho Kira — a site that has been studied several times over the past decades.

Previous excavations revealed human remains and tools of a very specific type called “Initial Upper Palaeolithic.”

Such stone and bone tools, said Hublin, show features both of tools known to have been used by Neanderthals and toolkits used by later modern humans, with much debate over which hominin was making them.

However previous dating of the site ran into a number of difficulties, including from contamination.

Now Hublin and colleagues have carried out new excavations, and unearthed more tools and remains, including bone fragments and a tooth revealed, by methods including ancient DNA analysis, to be from early modern humans.

The team report that radiocarbon dating of modern human remains found in the same layer as the tools, suggested the remains dated to between 46,790 and 42,810 years ago, while a dating technique based on the rate of changes in DNA from mitochondria, the “powerhouses” of cells, suggested a date of between 44,830 and 42,616 years ago.

The team add the same sort of tools were found in the layer beneath, alongside animal remains dating to almost 47,000 years ago.

“We are talking about the oldest modern humans in Europe,” said Hublin adding that their archeological context is “crystal clear.”

In other words, this group was making Initial Upper Palaeolithic tools.

Among further discoveries the researchers found jewelery fashioned from cave bear teeth that they say is strikingly similar to that produced by the very last Neanderthals. That, they say, adds weight to the idea the latter may have adopted innovations as a result of contact with early modern humans.

“Some people would say that is a coincidence, I don’t believe it,” said Hublin, noting there is already genetic evidence that the groups interbred. “I don’t see how you can have biological interaction between groups without any sign of behavioral influence of one on the other.”

Prof Chris Stringer, an expert in human origins from London’s Natural History Museum, said while his own team previously discovered what is possibly an incomplete modern human skull in Greece from more than 200,000 years ago, the new research is important.

“In my view this is the oldest and strongest published evidence for a very early Upper Palaeolithic presence of Homo sapiens in Europe, several millennia before the Neanderthals disappeared,” he said, although he said doubt remained about whether Neanderthals were influenced in their jewelery making by early modern humans.

But Stringer added the new study highlights several mysteries including why the appearance of such early modern humans in Europe 46,000 years ago didn’t lead to their earlier establishment and an earlier disappearance of Neanderthals.

“One possibility is that the dispersals into Europe [of modern humans of the Initial Upper Palaeolithic] were by pioneering, small bands, who could not sustain their occupations in the face of a (then) larger Neanderthal presence, or the unstable climates of the time,” he said.

Words of the Year are not just interesting, they are telling. They are language and attitude barometers that measure what a country sees as important. The trending vocabulary around AI last year reveals a stark divergence in what each society notices and responds to the technological shift. For the Anglosphere it’s fatigue. For China it’s ambition. For Taiwan, it’s pragmatic vigilance. In Taiwan’s annual “representative character” vote, “recall” (罷) took the top spot with over 15,000 votes, followed closely by “scam” (詐). While “recall” speaks to the island’s partisan deadlock — a year defined by legislative recall campaigns and a public exhausted

In the 2010s, the Communist Party of China (CCP) began cracking down on Christian churches. Media reports said at the time that various versions of Protestant Christianity were likely the fastest growing religions in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The crackdown was part of a campaign that in turn was part of a larger movement to bring religion under party control. For the Protestant churches, “the government’s aim has been to force all churches into the state-controlled organization,” according to a 2023 article in Christianity Today. That piece was centered on Wang Yi (王怡), the fiery, charismatic pastor of the

Hsu Pu-liao (許不了) never lived to see the premiere of his most successful film, The Clown and the Swan (小丑與天鵝, 1985). The movie, which starred Hsu, the “Taiwanese Charlie Chaplin,” outgrossed Jackie Chan’s Heart of Dragon (龍的心), earning NT$9.2 million at the local box office. Forty years after its premiere, the film has become the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute’s (TFAI) 100th restoration. “It is the only one of Hsu’s films whose original negative survived,” says director Kevin Chu (朱延平), one of Taiwan’s most commercially successful

The primaries for this year’s nine-in-one local elections in November began early in this election cycle, starting last autumn. The local press has been full of tales of intrigue, betrayal, infighting and drama going back to the summer of 2024. This is not widely covered in the English-language press, and the nine-in-one elections are not well understood. The nine-in-one elections refer to the nine levels of local governments that go to the ballot, from the neighborhood and village borough chief level on up to the city mayor and county commissioner level. The main focus is on the 22 special municipality