British-Indian artist Anish Kapoor , 66, is mounting his largest-ever UK exhibition of outdoor sculpture at Houghton Hall in Norfolk from late this month, including his famous Sky Mirror, a five-meter stainless steel disc that turns the world around it upside down.

Sarah Crompton: What kind of things did you want to show at Houghton Hall?

Anish Kapoor: It’s one of the great houses of England, with a great history, and extensive grounds. I decided the stone works that I’ve made over the past 25 years, and I’ve never shown in the UK before, would sit quite well there. Then it felt right to put in some mirror works, and put the Sky Mirror in the grounds. It came together as quite a precise project.

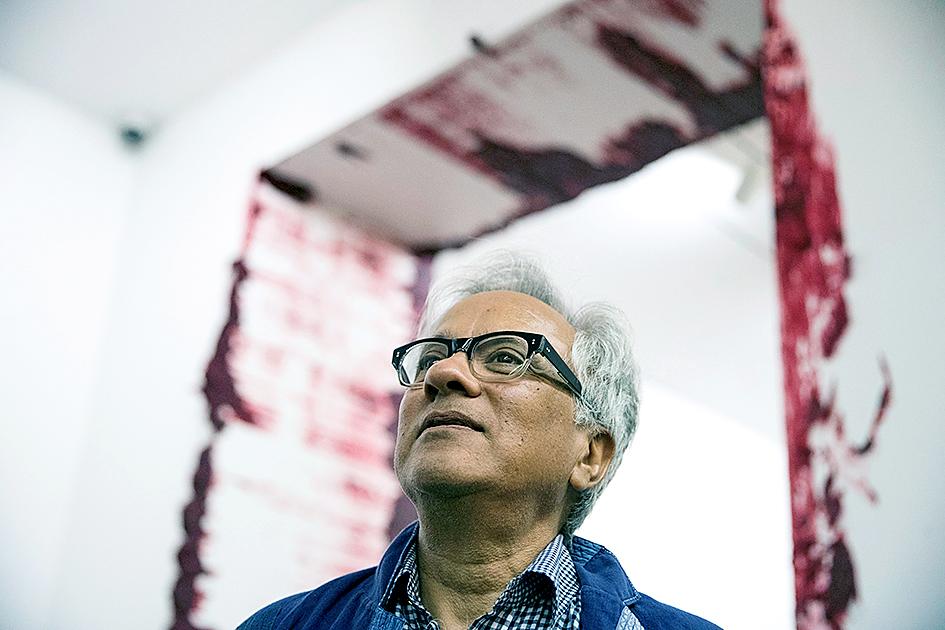

Photo: EPA-EFE

SC: What are you investigating with the stone sculptures?

AK: Most stone carving, over the last centuries, has been to have a block of stone, and then carve, like Michelangelo did, from outside in. What I’ve been doing, perversely, is to carve the interior. The block stays as it was quarried, and then I’ve been working on the inner form.

SC: Do you have a sense of yourself when you mount a retrospective exhibition?

Photo: AFP

AK: Yes, inevitably. I don’t like retrospectives, really. I’m looking to bring to life bodies of work that I hope make sense together. I seem to have a disjointed practice, because on the one hand I’m making these very geometric, very pure objects; and on the other my work is messy and all over the place — whether it’s a great pile of wax or these ritualistic paintings that I am making for an exhibition at the Modern Art Oxford gallery in September. Yet they are one practice — and they are, in a way, very similar to each other.

SC: What’s your overarching description of what you do?

AK: Oh God, I’ve no idea! [Laughs] I really do feel very strongly that I have nothing to say; I have no message to give the world and nor do I want to give the world a message. What I’m looking to do is to make objects that question the nature of objects — stones that are empty; heavy that’s not heavy, black objects that veil themselves?

Photo: EPA-EFE

SC: The black objects you are making with Vantablack, the world’s darkest black substance, will be shown for the first time in the Accademia in Venice next year. They are thrilling.

AK: I’m very excited by them. The material is, in a way, mythological. Imagine being able to describe a material as the blackest in the universe — including black holes. That’s kind of daft, isn’t it?

SC: How do you think it is now for young artists?

Photo: EPA-EFE

AK: Incredibly difficult. I think the art world is in severe difficulty. At one level, it’s booming. But what does that mean for artists? We are not makers of luxury goods.

I am part of that system too, so I’m not speaking as an outsider. But if everything’s for sale, how is it possible to find anything that’s radical? It’s so hard to maintain one’s distance from the commodification of the object.

And for young artists today, it’s impossibly hard to find space in London, it’s so goddamn expensive. When I first had a studio in east London in the early 80s it cost £5 a week...

SC: What advice would you give to someone starting out?

AK: It’s taking your metier as an artist thoroughly, absolutely, totally seriously. It’s not a part-time activity it is what we do all the time. Perseverance and endurance, or something like it, that’s what you need.

SC: Do you still work every day?

AK: Oh yes, I have a practice. I think Mae West once said: “I’m so tired of being admired.” I’m so tired of being inspired. Inspiration is marvellous, but it’s not really about that. I work a very normal day, 8.30am to 7pm, five days a week — I don’t work on a weekend. And it’s through the practice of working that things occur. It doesn’t matter what you do. Just do it.

SC: You were vocally opposed to Brexit. What’s your feeling now?

AK: It continues to be a disaster. Psychically it’s about where we are and how we see ourselves. This idea that Britain can do special deals and play a big nation I think it’s a fantasy. An isolationist, sad fantasy. Yet political discourse has almost ceased on the subject. I hope it will return.

SC: Would it make you think about leaving?

AK: I’ve had serious thoughts about leaving. And sad thoughts, because I’ve been here 40 years.

SC: Why do you feel the need to speak out?

AK: We’re all citizens, and as citizens we have a voice. I feel it’s important to engage, but I do believe that’s different from agitprop.

My art has its political position but it isn’t speaking in a political voice. But as a citizen I do! And so, stupid or otherwise, I’ll continue.

SC: You’ve recently managed to stop the National Rifle Association of America using an image of your Chicago sculpture Cloud Gate in one of their films?

AK: Yes, I did. They put out a vile little film using public objects as images of the so-called liberal invasion of traditional American space. I thought the whole way it was done was revolting, so I decided to fight on the basis of copyright. A group of American lawyers took it on pro bono, and I agreed to pay their expenses. They say it was the first action to cause the NRA to retreat from a position , and they’ve been retreating ever since. Yay!

SC: On the subject of public sculpture, The Orbit, which you designed for the Olympic Park in east London, is apparently losing a lot of money?

AK: It was made as a public sculpture, then Boris Johnson, in his previous incarnation [as mayor of London], turned it into a — what do they call it? — a visitor attraction. Oh, Jesus! I could have had a war with him, but I didn’t want to. But it always was a bad idea, according to me. Either you do something as a public object, or it’s a commercial enterprise. To mix the two up is confusion. It doesn’t work.

SC: Generally, you always seem enthusiastic and curious. Is that true?

AK: I’m an idiot, you know. Just deeply engaged in what I’m doing. I’m not interested in doing what I know how to do. I’ve just had my 66th birthday and I hope I can work with the same kind of idiotic enthusiasm that I had when I was 20.

Behind a car repair business on a nondescript Thai street are the cherished pets of a rising TikTok animal influencer: two lions and a 200-kilogram lion-tiger hybrid called “Big George.” Lion ownership is legal in Thailand, and Tharnuwarht Plengkemratch is an enthusiastic advocate, posting updates on his feline companions to nearly three million followers. “They’re playful and affectionate, just like dogs or cats,” he said from inside their cage complex at his home in the northern city of Chiang Mai. Thailand’s captive lion population has exploded in recent years, with nearly 500 registered in zoos, breeding farms, petting cafes and homes. Experts warn the

The unexpected collapse of the recall campaigns is being viewed through many lenses, most of them skewed and self-absorbed. The international media unsurprisingly focuses on what they perceive as the message that Taiwanese voters were sending in the failure of the mass recall, especially to China, the US and to friendly Western nations. This made some sense prior to early last month. One of the main arguments used by recall campaigners for recalling Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers was that they were too pro-China, and by extension not to be trusted with defending the nation. Also by extension, that argument could be

Aug. 4 to Aug. 10 When Coca-Cola finally pushed its way into Taiwan’s market in 1968, it allegedly vowed to wipe out its major domestic rival Hey Song within five years. But Hey Song, which began as a manual operation in a family cow shed in 1925, had proven its resilience, surviving numerous setbacks — including the loss of autonomy and nearly all its assets due to the Japanese colonial government’s wartime economic policy. By the 1960s, Hey Song had risen to the top of Taiwan’s beverage industry. This success was driven not only by president Chang Wen-chi’s

Last week, on the heels of the recall election that turned out so badly for Taiwan, came the news that US President Donald Trump had blocked the transit of President William Lai (賴清德) through the US on his way to Latin America. A few days later the international media reported that in June a scheduled visit by Minister of National Defense Wellington Koo (顧立雄) for high level meetings was canceled by the US after China’s President Xi Jinping (習近平) asked Trump to curb US engagement with Taiwan during a June phone call. The cancellation of Lai’s transit was a gaudy