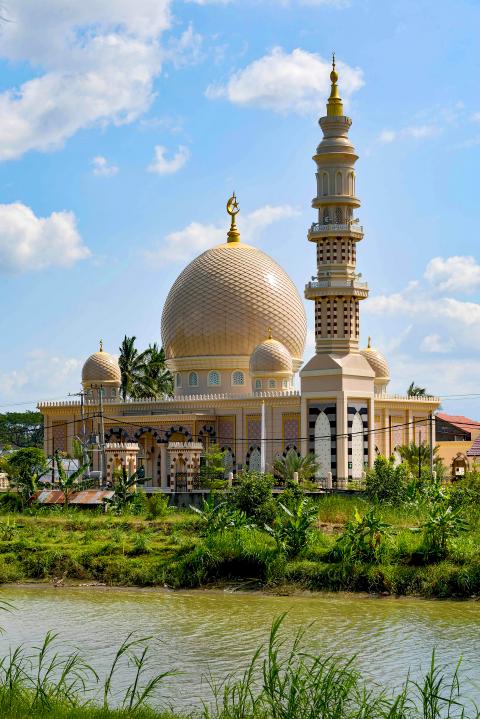

As Friday prayers wrap up at Suada mosque, worshipers turn their attention outside where Fakhry Affan steers a drone high above, snapping pictures of the building tucked in a corner of Indonesia’s Sulawesi island.

Affan leads a government team of some 1,000 mosque hunters who have spent years visiting every corner of the 5,000km long archipelago to answer one question: how many mosques are there in the world’s biggest Muslim majority nation?

“Only God knows exactly how many mosques there are in Indonesia,” former vice president Jusuf Kalla quipped recently. “Some say around one million and people will take it for granted.”

Photo: AFP

So far, Affan’s team has registered 554,152 mosques and the census — which kicked off in 2013 — is only about 75 percent done, Affan says. Earlier government estimates pegged the total at more than 740,000 nationwide.

Nearly 90 percent of Indonesia’s 260 million people are Muslim and it is home to Jakarta’s Istiqlal mosque, Southeast Asia’s biggest with room for 200,000 worshipers. So it’s an Herculean task for Affan and his team at the religious affairs ministry as it scours a country of some 17,000 islands, where new mosques are going up all the time.

After getting key information about Mamuju city’s 3,000 capacity Suada mosque — including building permit and mosque committee details — Affan uploads his drone pictures to a bulging online database.

Photo: AFP

“We did it manually in the past, but now we’re going digital,” he said.

The government is also planning to launch an Android-based app called Info Masjid (Mosque Info) so Muslims can use their smartphone to find the nearest place of worship.

Nur Salim Ismal, who attends the Suada mosque, hopes the move online will bring greater transparency.

Photo: AFP

“Mosques manage huge amounts of money from worshipers and it should be clear how it’s being used,” he said.

But the mosque hunt isn’t just a counting exercise — it’s also a way to keep an eye on radicalism.

“Radical ideology can mushroom anywhere and mosques are one of the easiest places for it to spread,” Affan said. “Why? Because you don’t need to invite people to the mosque, they’ll come anyway.

“We want to ensure that all imams and (mosque) committees are moderate because Islam in Indonesia is moderate,” he added.

Indonesia’s long-held reputation for tolerant pluralism has been tested in recent years.

Muslim hardliners are becoming increasingly vocal in public and the country is home to dozens of extremist groups loyal to Islamic State group’s violent ideology.

In 2018, Indonesia’s intelligence agency said it had found dozens of mosques that catered to government workers spreading radicalism and calling for violence against non-Muslims — in one Jakarta neighborhood alone.

The alarming figures came several months after Indonesia’s second-biggest city Surabaya was rocked by a wave of suicide bombings carried out by families at churches during Sunday services, killing a dozen people. Members of an IS-loyal group tried to assassinate Indonesia’s chief security minister last year, while in November a militant suicide bomber killed himself and injured six others during an attack at a police station.

Indonesia’s new vice-president Ma’ruf Amin, a cleric-turned-politician, has said the government would start certifying preachers and mosque congregations nationwide to stamp out militants in their ranks.

“There is potential for mosques to be prone to radicalism if they’re not monitored,” said Ali Munhanif, an expert on political Islam at Syarif Hidayatullah State Islamic University Jakarta.

“The government has a responsibility to keep its eye on all mosques in Indonesia.”

In the tally so far, the team has counted 258,958 large mosques and another 295,194 smaller ones, which fit 40 people or fewer. Affan and his team hope to finish the initial round of counting this year. “But this is an endless job and it’ll never be finished,” he said.

“It’s pretty rare for a mosque to close down, but one thing is for sure: the number of new ones will keep going up.”

Following the shock complete failure of all the recall votes against Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers on July 26, pan-blue supporters and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) were giddy with victory. A notable exception was KMT Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫), who knew better. At a press conference on July 29, he bowed deeply in gratitude to the voters and said the recalls were “not about which party won or lost, but were a great victory for the Taiwanese voters.” The entire recall process was a disaster for both the KMT and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). The only bright spot for

Water management is one of the most powerful forces shaping modern Taiwan’s landscapes and politics. Many of Taiwan’s township and county boundaries are defined by watersheds. The current course of the mighty Jhuoshuei River (濁水溪) was largely established by Japanese embankment building during the 1918-1923 period. Taoyuan is dotted with ponds constructed by settlers from China during the Qing period. Countless local civic actions have been driven by opposition to water projects. Last week something like 2,600mm of rain fell on southern Taiwan in seven days, peaking at over 2,800mm in Duona (多納) in Kaohsiung’s Maolin District (茂林), according to

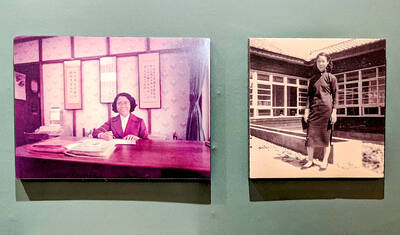

Aug. 11 to Aug. 17 Those who never heard of architect Hsiu Tse-lan (修澤蘭) must have seen her work — on the reverse of the NT$100 bill is the Yangmingshan Zhongshan Hall (陽明山中山樓). Then-president Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) reportedly hand-picked her for the job and gave her just 13 months to complete it in time for the centennial of Republic of China founder Sun Yat-sen’s birth on Nov. 12, 1966. Another landmark project is Garden City (花園新城) in New Taipei City’s Sindian District (新店) — Taiwan’s first mountainside planned community, which Hsiu initiated in 1968. She was involved in every stage, from selecting

As last month dawned, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was in a good position. The recall campaigns had strong momentum, polling showed many Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers at risk of recall and even the KMT was bracing for losing seats while facing a tsunami of voter fraud investigations. Polling pointed to some of the recalls being a lock for victory. Though in most districts the majority was against recalling their lawmaker, among voters “definitely” planning to vote, there were double-digit margins in favor of recall in at least five districts, with three districts near or above 20 percent in