Jan. 6 to Jan. 11

Protesters from the Presbyterian Church in Taiwan surrounded a police car in the afternoon of Jan. 8, 1988, after discovering a cache of wooden clubs, spears and swords inside. They demanded to know if the weapons were to be used against them, and the situation escalated as the two sides clashed.

The churchgoers had gathered in support of Tsai Yu-chuan (蔡有全) and Hsu Tsao-te (許曹德), who were being tried for advocating Taiwanese independence at an event to celebrate the establishment of the Taiwan Political Victims Association (台灣政治受難者聯誼總會).

Photo courtesy of Tsai Yu-chuan

Tsai was a graduate of the church’s Tainan Theological College and Seminary. But the church’s involvement with Taiwanese independence dated back to August 1977, when it publicly declared that “Taiwan’s future should be decided by the 17 million residents of Taiwan.”

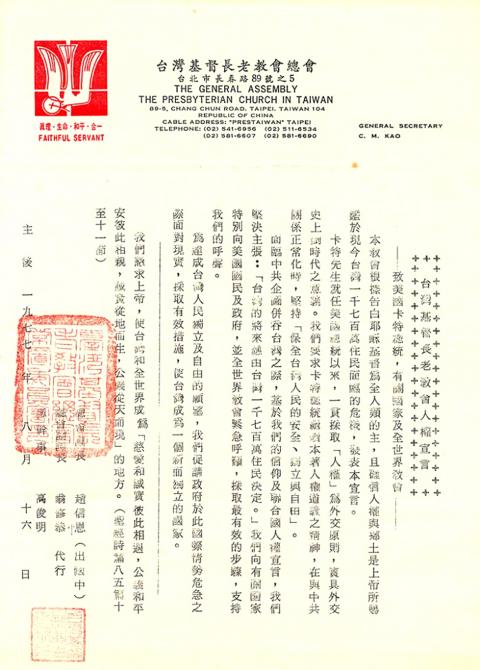

“To realize the wishes of Taiwanese to be independent and free, we urge the government to face the reality in this precarious international situation and take effective measures to make Taiwan a new and independent country,” the church said.

The church retains its stance to this day, continuing to urge the government through public statements.

Photo courtesy of Presbyterian Church of Taiwan

THE PIOUS GET POLITICAL

In his memoirs, the late Reverend Kao Chun-ming (高俊明) writes that bad blood between the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Presbyterian Church in Taiwan began in the late 1960s, when the World Council of Churches (WCC) started supporting China’s entry to the UN and allowed several Chinese churches to join their organization.

The KMT was not happy, and essentially forced the Presbyterian Church in Taiwan to leave the WCC in 1970, presaging how Taiwan walked out of the UN when China was admitted a year later.

Photo: Fang Pin-chao, Taipei Times

Kao, who took leadership of the church in July 1970, released the first of three public declarations in December 1971.

He criticized the US for “selling out Taiwan” to repressive communist powers and urged the KMT to embrace democracy, so that Taiwan could still be respected by the world despite no longer being a UN member. Taiwanese independence was not yet mentioned; the church merely did not want Taiwan to be swallowed by China after losing its international clout.

“Nobody had spoken out despite our precarious situation, so the church decided that we needed to risk our lives and risk being shut down by the government to express the desires of most Taiwanese,” Kao recalls in his memoirs.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Despite government interference, the church managed to get the message out.

Afterward, Reverend Daniel Beeby of the Tainan Theological College and Seminary was expelled from Taiwan in 1972 for urging his students to embrace independence or risk being conquered by China. To him, the KMT’s insistence on the “one China” policy would only further marginalize Taiwan and lead to its eventual demise. Tsai, a fellow graduate of the seminary, would echo these sentiments in his struggles later on.

In 1975, the KMT confiscated the church’s Hoklo (also known as Taiwanese) Bibles and banned worshipers from singing Hoklo hymns. Coupled with then US President Gerald Ford’s upcoming visit to China, the church decided it was time for a second statement despite grave warnings from the KMT.

Photo courtesy of Tsai Yu-chuan

This statement was mostly focused on religious freedom, and advised the government to stop banning civic groups from joining international organizations just because they also allowed Chinese membership.

SENT TO JAIL

But Taiwan’s international situation only continued to worsen. By 1977, rumors were swirling that the US was about to break ties with Taiwan for China. Church leaders knew that they would get in trouble for their third statement openly advocating Taiwanese independence, and Kao writes that he and many pastors prepared their wills.

Kao narrowly avoided arrest, despite attempts by the government, probably due to the international clout of the church. But he became a marked man.

During this time, Tsai and other Tainan Theological College and Seminary students grew closer to dangwai (黨外) opposition politicians, with several joining the staff of the anti-KMT Formosa magazine (美麗島).

Tsai was one of several people with ties to the church who were arrested in the aftermath of the Kaohsiung Incident, in which protestors clashed with police at a pro-democracy rally organized by Formosa magazine. He was sentenced to five years in jail.

While Kao was not directly involved, he and several others were arrested a few months later for helping opposition politician Shih Ming-te (施明德) hide from the authorities. Kao served four years in prison.

After martial law was lifted in 1987, Tsai and Hsu immediately helped form the Taiwan Political Victims Association.

Hsu, who was also jailed for several years due to his activism, included the clause “Taiwan should be independent” in the association’s by-laws. And in a speech that same night, Tsai called for Taiwanese independence.

Both were arrested shortly after and sentenced to 10 and 11 years in prison respectively. The church strongly protested, calling for freedom of speech and taking to the streets several times during their trial.

Cheng Mu-chun (鄭睦群) writes in Taiwan Nation: The Presbyterian Church’s National Identity (從大中華到台灣國: 台灣基督教長老會的國家認同及其論述轉換) that despite its 1977 statement, the church tried to distance itself from the independence movement, declaring several times that their words were misinterpreted.

But after Tsai’s arrest and the April 1989 self-immolation of democracy activist Deng Nan-jung (鄭南榕), the church’s official Taiwan Church News (台灣教會公報) newsletter started openly publishing articles supporting independence, confirming the stance that it maintains to this day, Cheng writes.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

Lines between cop and criminal get murky in Joe Carnahan’s The Rip, a crime thriller set across one foggy Miami night, starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Damon and Affleck, of course, are so closely associated with Boston — most recently they produced the 2024 heist movie The Instigators there — that a detour to South Florida puts them, a little awkwardly, in an entirely different movie landscape. This is Miami Vice territory or Elmore Leonard Land, not Southie or The Town. In The Rip, they play Miami narcotics officers who come upon a cartel stash house that Lt. Dane Dumars (Damon)