April 22 to April 28

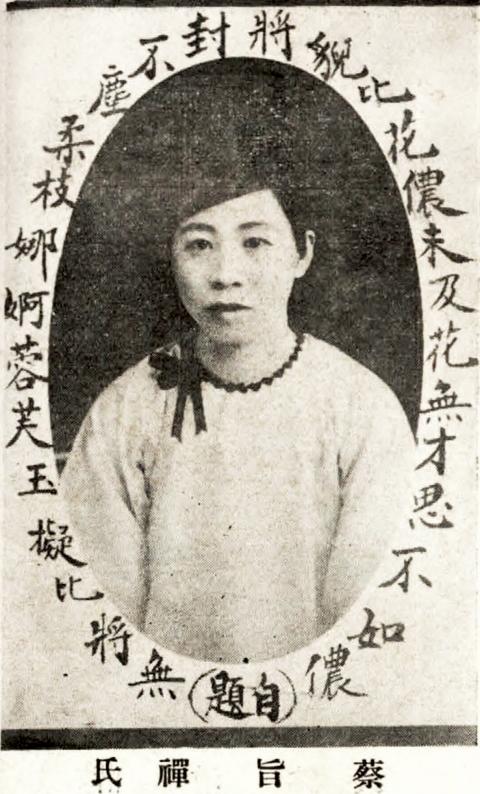

According to Penghu County records (澎湖縣志), Tsai Chih-chan (蔡旨禪) was born after her childless parents prayed to the Buddhist goddess of compassion, Guanyin (觀音).

“She was a virtuous and gifted child with great intelligence, distinguishing herself from her peers at a young age. She enjoyed embroidery and drawing instead of playing, and by the age of nine, she had become a vegetarian and devout Buddhist,” the records state about Tsai.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Whether true or not, embellished biographies involving deities are reserved for extraordinary people. Tsai was born in on April 28, 1900 in the Japanese-ruled backwaters of Penghu to parents of modest means — not exactly the right elements for a woman to make something of her life.

Tsai grew up to be a well-respected poet, her work appearing in numerous publications between 1923 and 1937. At the age of 24, she became Penghu’s first ever female Chinese-language teacher. When she accepted a teaching position in Changhua the following year, she named her school “Pingquanxuan” (平權軒), literally the “Equal Rights Pavillion.” Before Tsai left Penghu, she wrote a poem to her classmates, one verse expressing her desire to “make my name known as a woman.”

Tsai wasn’t the only prominent female poet in those days. In a 1933 island-wide poetry anthology from which Tsai’s only known photo was procured, there were several other women featured in the author introduction pages. Notable names include Huang Chin-chuan (黃金川), who authored Taiwan’s earliest known anthology of classical poems by a woman, and Chang Lee Te-ho (張李德和), another accomplished poet and painter who later served in the Taiwan Provincial Assembly.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Historian Lee Yu-lan (李毓嵐) writes in the study that the 1920s saw the awakening of Taiwanese women as they started participating in public affairs; the local newspapers ran many columns discussing new attitudes toward females regarding marriage, education, work and even entering politics.

The same period, for example, produced Taiwan’s first female physician Tsai A-hsin (蔡阿信, born 1899) as well as Hsu Shih-hsien (許世賢, born 1908), Taiwan’s first woman to earn a doctorate degree. Both have been featured in previous Taiwan in Time columns on June 5, 2016 and June 24 last year, respectively.

A CELEBRATED DEBUT

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Although women’s roles were still fairly restricted at the turn of the 20th century, change was brewing. The year Tsai was born, a group of intellectuals and businessmen formed the “Taipei Natural Feet Association” (台北天然足會), which aimed to stop the crippling practice of foot binding for women, which was more prevalent among the upper class. The group also encouraged women to go to school and handed out badges to women who unbound or never bound their feet.

Other groups worked with the government to set up vocational training centers for women, encouraging them to step beyond home labor. The government’s aim was not so much to promote gender equality, but to increase Taiwan’s labor force to speed up the colony’s industrial development.

Tsai reveals in a poem that she decided by the age of nine to never marry and devote herself to Buddhism so she could support and take care of her parents. It may seem odd today, but Tsai was proud of her decision, which was widely praised by her contemporaries as virtuous.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Wei Hsiu-ling (魏秀玲) writes in Study of Tsai Chih-chan and her Poetry and Painting Collection (旨禪詩畫集) that Tsai likely never received a formal Japanese education, instead acquiring her literary skills from private tutors who taught Chinese classics. One of her teachers was Chen Hsi-ju (陳錫如), who hailed from the same township in Penghu. Before returning home in 1923, Chen was known for training 12 talented female writers in what is today’s Kaohsiung area, and Tsai commends Chen in a 1927 anthology for his efforts in preserving Chinese education under colonial rule and encouraging female education.

After just a year under Chen, Tsai submitted her first poem to Penghu’s Xiying Poetry Society (西瀛吟社), surprising her peers by winning one of the top prizes. Her male peers praised her accomplishment — Yen Chi-shuo (顏其碩) wrote three verses celebrating the feat, and the national Taiwan Daily News (台灣日日新報) also reported her win, calling it a “rare occurrence.”

In April 1924, Tsai took on her first batch of students. The Tainan New Post (台南新報) noted on April 23 that she was the first female to teach Chinese in hundreds of years of Penghu history.

TUTORING TAIWAN’S ELITE

By the end of 1924, Tsai packed her bags and took her parents with her to Taiwan, where she was hired as a teacher in Changhua. This was again reported in the Tainan New Post, which marked it as a milestone for female accomplishment.

She was later employed by the prominent Wufeng Lin family (霧峰林家) to educate the female members of the household, becoming close with family head Lin Hsien-tang (林獻堂) and his wife, Yang Shuei-hsin (楊水心). Through them she gained access to many high society functions, including Lin’s cultural organization Yixinhui (一新會), which boasted 65 females out of about 300 members — an impressive gender ratio for those days. The women were not only encouraged to attend public functions and speak up, they actively participated as decision makers.

Lin was the head of the Taiwan Cultural Association (台灣文化協會), which added “respecting the character of women” to its annual objectives in 1923. While there was much discussion on the role of women domestically in the 1920s, many upper class Taiwanese also had the chance to travel abroad and see how differently women were treated. Lin, in particular, took note of the respect and opportunities given to Western women when he spent over a year traveling the world in 1927 and 1928. As always, this attitude wasn’t across the board as members protested Lin giving equal rights to women in the Taiwan Cultural Association. Lin responded that women should be treated as human beings and that their inferiority was due to lack of education.

When Tsai headed to Hsinchu for another teaching post in 1932, the Shi Bao (詩報) poetry publication noted that she “had deep beliefs in emancipation.” In a footnote, the author explained that “emancipation” referred to Tsai’s “determination to seek equal rights and freedom for women” and “to remain free of the shackles of men and superstitions.”

In addition to poetry, Tsai also developed an interest in painting, and Lin sponsored her in 1934 to travel to Xiamen to take classes. Studying abroad was something reserved for the elite, but Tsai was determined enough to find a way. Tsai remained active until about 1937 — around the time the colonial government started banning all things Chinese through the Kominka Movement (皇民化運動).

She returned to Penghu in 1955, only to find that part of Chengyuan Temple (澄源堂), where she taught her first students, was occupied by Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) troops and their families. She and her brother sued and obtained the rights to it in 1957, and Tsai ran the temple for a year until she died.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an