March 25 to March 31

“Chinese Communist major-general killed by Lee Teng-hui’s (李登輝) words,” screamed the headlines in most major newspapers that were covering the reopening of the Dai Li Memorial Hall (戴雨農先生紀念館) in March last year.

The officer in question was Liu Liankun (劉連昆), who was revealed to be honored in the hall among 75 intelligence officers killed in the line of duty. Liu was the highest-ranking People’s Liberation Army (PLA) officer known to have spied for Taiwan. He was arrested by Chinese authorities on March 29, 1999 and subsequently executed.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Lee’s “words” were spoken on March 7, 1996 at the height of the Third Taiwan Strait Crisis. Beijing was determined to prevent then-president Lee from being reelected, and word was that it would soon conduct missile tests aimed at Taiwan.

In a speech, Lee claimed that the missiles were blanks, and assured the public that he had already prepared several scenarios to deal with the situation. China fired three missiles the next day into waters alarmingly close to Taiwan; as Lee predicted, they didn’t have a payload.

The story broadcast in the media was that Lee had learned of the missiles from Liu’s intelligence reports, and by leaking the information in his speech, he had alerted Beijing to a major rat in their ranks. After conducting a thorough investigation, the Chinese homed in on Liu.

Photo courtesy of Military Intelligence Bureau

However, Lee has repeatedly denied that his remarks had anything to do with Liu’s intelligence. Then-minister of defense Chiang Chung-ling (蔣仲苓) stated in the immediate aftermath that Lee had made the correct guess due to his “extensive knowledge of missiles,” with the ministry further noting that it is common knowledge that most countries don’t arm their missiles in long-range tests.

“The aim is to test the accuracy of the missile, so why waste a warhead?” concurred a Taipei Times editorial on June 30, 2001 titled “The unmaking of a spy.”

IMPLICATIONS OF LEE’S SPEECH

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Looking back on old news reports, it seems that the earliest claim that Lee’s remarks caused Liu’s death came from a Washington Post article from Feb. 20, 2000 titled “Taiwanese mistake led to 3 spies’ executions.”

In that article, an unnamed “senior Taiwanese government official” stated that the government had indeed received intelligence from Liu and that Lee should not have revealed it.

“We should have used other methods to calm our population.”

Furthermore, the official said that the government had tried to get Liu out of China right after the presidential elections, but bureaucratic foul-ups delayed the process, leading to his arrest.

Just two weeks later, disgruntled intelligence officer Chang Chih-peng (張志鵬) held a press conference claiming that Lee’s “careless remarks” had seriously compromised Taiwan’s intelligence network in China, leading to the death of Liu and many others. Chang was allegedly the one who brought to Taiwan the intelligence Liu had provided on China’s plans for the missile crisis.

The story blew up after Chang later threatened to turn himself in to Chinese authorities if the government didn’t pay him NT$100 million. In response, Lee reiterated his claim that he had only guessed that the missiles were unarmed. The Ministry of National Defense refused to comment, stating that “no nation would discuss in public its intelligence network.”

Eighteen years later, Taiwan’s increasingly sensationalist media jumped on the salacious story again, citing few to no sources and quoting clueless netizens, with only a few reporters bothering to look into the details behind Liu’s career and eventual capture.

‘SHAOKANG 2’

Ostensibly due to his position as a spy, few reputable sources provide details about Liu’s life. The Washington Post article provides some details, as well as a 50-minute special produced by the US government-funded Voice of America in 2014. An out-of-print book, The 70-year Espionage War between the Nationalists and Communists (國共間諜戰七十年), is only available at the National Central Library, and unfortunately the section on Liu has been ripped out.

Born in 1933, Liu had attained his rank of major-general by the late 1980s and reportedly served as deputy director of the PLA’s General Logistics Department. The Washington Post says that Liu was an easy target for Taiwanese agents because “he felt he had been wrongly implicated in an army corruption scandal and denied a promotion.”

The Voice of America, however, claims that Liu’s distaste toward the PLA began with the Tiananmen Square Massacre, and after being warned by his superiors for speaking out against the violence, he noticed that his phones were being tapped.

Taiwan’s Military Intelligence Bureau (MIB) recruited Liu in what it called the Shaokang Program (少康專案), with Liu’s codename as “Shaokang 2.” “Shaokang 1” was Shao Zhengzong (邵正宗), a PLA colonel who was in charge of convincing Liu to turn.

In late 1992, Taiwanese agents led by Pang Ta-wei (龐大為) secretly met Liu, Shao, Chang and others in Guangzhou. Liu took the train from Beijing instead of a plane to avoid detection. This was the only time Pang and Liu met. Pang tells Voice of America that he gave Liu two bottles of top grade wine and US$20,000 as an initial gift, promising to pay Liu according to his military rank in addition to bonuses for providing information — namely advance military information.

From then on, Liu provided information on China’s major military purchases, its strategy on retaking Taiwan by force as well as its plans on the handover of Hong Kong. Three months before the PLA started conducting military exercises to threaten Taiwan’s electorate in the run-up to the nation’s first-ever popular presidential election, Liu had allegedly already leaked the entire plan to Taiwan’s military. Through Liu, they found that the PLA was not only planning to take over a few minor islands, it was willing to turn the exercises into actual military operations if they were not happy with the election results.

Taiwanese authorities alerted the US, whose involvement led the PLA to tone down its actions. Liu then informed Taiwan that China would not actually attack, and its missiles wouldn’t fly over Taiwan nor would they be armed.

AFTERMATH

The Voice of America production maintains that it’s still a mystery as to how exactly Liu was caught. Pang says that while Lee’s speech may have alerted the Chinese authorities to a high-ranking spy in their ranks, there would have to have been other factors in play, including a Chinese spy working against him and possibly tapped phone conversations between Liu and MIB agents.

Even Chang told the Taipei Times in 2001 that the direct reason Liu was caught was due to a careless error by Taiwanese authorities that led Beijing to discover a cassette tape with Liu’s voice on it.

Liu’s case reportedly involved over 200 people, many of whom were imprisoned, including his son. Shao was executed for his role. Chang never got the NT$100 million he asked for, settling for NT$30 million and a monthly retirement fund. Pang served three years in prison for publishing in Hong Kong an account of his espionage days in honor of Liu.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Following the shock complete failure of all the recall votes against Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers on July 26, pan-blue supporters and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) were giddy with victory. A notable exception was KMT Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫), who knew better. At a press conference on July 29, he bowed deeply in gratitude to the voters and said the recalls were “not about which party won or lost, but were a great victory for the Taiwanese voters.” The entire recall process was a disaster for both the KMT and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). The only bright spot for

Water management is one of the most powerful forces shaping modern Taiwan’s landscapes and politics. Many of Taiwan’s township and county boundaries are defined by watersheds. The current course of the mighty Jhuoshuei River (濁水溪) was largely established by Japanese embankment building during the 1918-1923 period. Taoyuan is dotted with ponds constructed by settlers from China during the Qing period. Countless local civic actions have been driven by opposition to water projects. Last week something like 2,600mm of rain fell on southern Taiwan in seven days, peaking at over 2,800mm in Duona (多納) in Kaohsiung’s Maolin District (茂林), according to

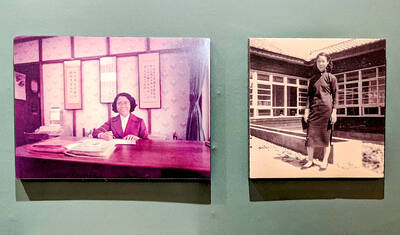

Aug. 11 to Aug. 17 Those who never heard of architect Hsiu Tse-lan (修澤蘭) must have seen her work — on the reverse of the NT$100 bill is the Yangmingshan Zhongshan Hall (陽明山中山樓). Then-president Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) reportedly hand-picked her for the job and gave her just 13 months to complete it in time for the centennial of Republic of China founder Sun Yat-sen’s birth on Nov. 12, 1966. Another landmark project is Garden City (花園新城) in New Taipei City’s Sindian District (新店) — Taiwan’s first mountainside planned community, which Hsiu initiated in 1968. She was involved in every stage, from selecting

As last month dawned, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was in a good position. The recall campaigns had strong momentum, polling showed many Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers at risk of recall and even the KMT was bracing for losing seats while facing a tsunami of voter fraud investigations. Polling pointed to some of the recalls being a lock for victory. Though in most districts the majority was against recalling their lawmaker, among voters “definitely” planning to vote, there were double-digit margins in favor of recall in at least five districts, with three districts near or above 20 percent in