Chen Kao-teng (陳高登) communicates with the objects he repairs — whether bowls, plates or teapots, he doesn’t discriminate. Chen does so, he says, because it’s the best way to channel his creativity, a lesson he learned from his mentor Lai Chih-hsien (賴志賢).

He would later discover that the process made him reapproach his attitude towards the polio he has had since he was a child.

“Lai taught me how to talk to the objects,” he says. “We think that as craftsmen we can do whatever we please with an object, but objects have souls.”

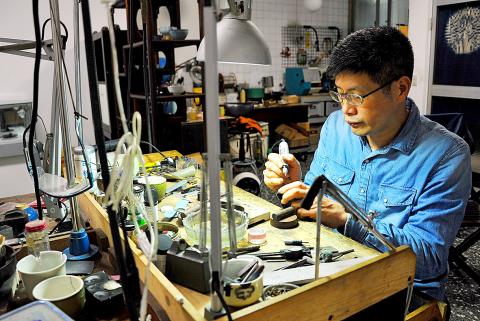

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei TImes

Chen, 52, is among a handful of craftspeople in Taiwan who earns a living repairing and repurposing broken, discarded and imperfect objects using the traditional craft of ceramic repair called juci (焗瓷).

The trade thrived during the Japanese colonial period when even the ritzy hotel Kangsanlau (江山樓) used plates during banquets that had been stapled together. It declined in the 1960s as the nation’s economy took off, while restaurants started using disposable plates and stores began selling NT$200 shoes. He also learned the Japanese art of kintsugu, which uses resin and gold or silver dust to fill cracks.

It wasn’t until 2013 that Chen and Lai received formal training from Chinese master Wang Laoxie (王老邪). Wang began his apprenticeship at the age of four as the grandson of a court repair craftsman for the Qing Empire.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei TImes

Since juci was dormant for decades, even “specialists” like Chen are relative newcomers. Originally a metalsmith, Chen accidentally discovered the craft while researching ways to fix a friend’s teapot. While Chen sought out Lai as the authority on juci for his Master’s thesis, Lai insists that he was no expert and only gleaned what he could by taking apart repaired antiques.

POLIO AND PERFECTION

In his studio, Chen motions towards the metal staples in a teapot. He tells me how they remind him of the numerous surgeries to correct the imperfections polio wrought on his childhood body.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei TImes

“Life isn’t perfect... But we can still find a way to repair things,” Chen says.

He came to this realization six years ago when he started to practice juci.

“I initially thought I was just making the damaged part look prettier,” he says. “But I realized I was also channeling my thoughts and feelings into the process. I started being less conscious about my disability, which I used to hide from everyone.”

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei TImes

In other words, perfection isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. Sometimes just because something is broken doesn’t mean it doesn’t have value.

“A person’s sentimental attachment to an object isn’t going to disappear just because they can afford something new,” Chen says. “[Some objects are] irreplaceable not only because of the customer’s emotional attachment to it, but also because another might not exist.”

Chen says most of his customers today bring him objects that have sentimental value — a family heirloom, for example, or a favorite pipe. At the prohibitive price of NT$2,000 to NT$3,000, fixing any old teapot wouldn’t make financial sense.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei TImes

Chen says there’s been a surge of interest in his skill due to an increased awareness of sustainability, reducing waste and green living, but there’s only a handful of artisans doing it for a living.

“I want people to think before they discard,” Lai says.

KEEPING AN OLD TRADE RELEVANT

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei TImes

Since traditional repairs are no longer a necessity, Chen and Lai say creativity keeps the trade relevant, from stapling a split tabletop in a way that resembles a flower to repurposing a broken teapot into an oil lamp and incense burner. Instead of restoring something to its original form, they breath new life and value into formerly defective objects, Lai says.

Lai takes his creativity a step further, often whimsically repurposing broken objects rather than mending them. There’s a clock in his shop adorned with pieces from a bowl too broken to mend, and a cup with a smashed bottom, turned candle holder.

GENERATING INTEREST

Chen has a small but steady supply of students at his studio or at the Beitou Museum (北投文物館), a restored Japanese residence near the hot springs. Most of the students are retirees or collectors of teapots or antiques, but there’s also a few younger ones. Chen has simplified and modified the procedures so they are more accessible to the average learner.

“If a carpenter comes, I’ll teach him how to fix things with wood so it’s easier for him. The point is the concept. Juci is more than just the staples.”

In Chen’s studio, Yeh Chih-chin (葉志錦) is learning to fix a favorite teapot and a crudely superglued cup his daughter brought back from Yellowstone National Park. Meanwhile, Huang Chen-yu (黃貞毓) is working on her father’s teapot and her father’s friend’s pipe. Both are career artists, Yeh a sculptor and Huang a jewelry maker.

“I like learning different crafts and my dad and his friend happened to have a bunch of stuff they wanted to repair,” Huang says. She doesn’t think the repair trade is dying out, but it’s becoming a niche skill that the average person isn’t likely familiar with.

Chen says the craft needs to be connected to something relevant and commercially viable, such as the tea industry or the trending Japanese wabisabi design aesthetics that focus on the beauty of imperfection.

And people are also looking to commercially bank on the “retro” feel of repaired objects. One of Chen’s students is a sushi chef who once went to a Japanese restaurant that served its food on elegantly repaired kintsugi plates. He wants to learn the skills from Chen to recreate that experience in his future restaurant.

Meanwhile in another part of the workshop, Lai points to a cracked plaque on the wall showing a Hoklo (also known as Taiwanese) idiom in Chinese characters: “Everything is fine.”

“I was going to repair this. But it kept telling me ‘everything is fine.’ So I just left it as it is and framed it,” he laughs.

The primaries for this year’s nine-in-one local elections in November began early in this election cycle, starting last autumn. The local press has been full of tales of intrigue, betrayal, infighting and drama going back to the summer of 2024. This is not widely covered in the English-language press, and the nine-in-one elections are not well understood. The nine-in-one elections refer to the nine levels of local governments that go to the ballot, from the neighborhood and village borough chief level on up to the city mayor and county commissioner level. The main focus is on the 22 special municipality

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) invaded Vietnam in 1979, following a year of increasingly tense relations between the two states. Beijing viewed Vietnam’s close relations with Soviet Russia as a threat. One of the pretexts it used was the alleged mistreatment of the ethnic Chinese in Vietnam. Tension between the ethnic Chinese and governments in Vietnam had been ongoing for decades. The French used to play off the Vietnamese against the Chinese as a divide-and-rule strategy. The Saigon government in 1956 compelled all Vietnam-born Chinese to adopt Vietnamese citizenship. It also banned them from 11 trades they had previously

Jan. 12 to Jan. 18 At the start of an Indigenous heritage tour of Beitou District (北投) in Taipei, I was handed a sheet of paper titled Ritual Song for the Various Peoples of Tamsui (淡水各社祭祀歌). The lyrics were in Chinese with no literal meaning, accompanied by romanized pronunciation that sounded closer to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) than any Indigenous language. The translation explained that the song offered food and drink to one’s ancestors and wished for a bountiful harvest and deer hunting season. The program moved through sites related to the Ketagalan, a collective term for the

As devices from toys to cars get smarter, gadget makers are grappling with a shortage of memory needed for them to work. Dwindling supplies and soaring costs of Dynamic Random Access Memory (DRAM) that provides space for computers, smartphones and game consoles to run applications or multitask was a hot topic behind the scenes at the annual gadget extravaganza in Las Vegas. Once cheap and plentiful, DRAM — along with memory chips to simply store data — are in short supply because of the demand spikes from AI in everything from data centers to wearable devices. Samsung Electronics last week put out word