Kunihiko Tanaka was peddling vinegar to sushi restaurants in western Japan when he spotted the opportunity that would change his life.

It was the 1970s, and the sushi industry was set to boom. But Tanaka thought it was seriously flawed in how it operated. Artisan chefs presided over restaurants with poor quality control. They charged different prices to different people for the same meal, and bills weren’t affordable to the average person, except for special occasions.

Tanaka decided to establish his own sushi restaurant. But he would do it differently. And so, with about US$26,000 that he’d borrowed, he opened his first restaurant in 1977, setting out on a path that would eventually lead to the founding of Kura Corp in 1995. The firm embraced a range of modern technologies, aiming to bring sushi to the masses. Kura is now Japan’s second-largest chain of kaiten sushi restaurants, where the food is delivered on revolving conveyor belts. It has a market value of US$1.2 billion and hundreds of outlets nationwide.

Photo: Bloomberg

“I believed kaiten sushi would keep the sushi legacy going,” Tanaka said in an interview at the company’s headquarters in rural Osaka, about three hours west of Tokyo by train. “And I was right.”

Kura’s restaurants are about as far away as it’s possible to get from the notion of sushi-making as a lifelong artisan craft. The chain uses robots in the kitchen for some tasks instead of expensive and sometimes erratic sushi chefs handling the food with their bare hands, and an express delivery order lane above the revolving conveyor belt that speeds dishes to customers’ tables.

Kura is also different from other firms in that it refuses to use additives or preservatives in its food. In a typical sushi restaurant, those would be in the vinegar for the sushi rice and the soy sauce and wasabi mustard used to flavor the sushi, but in Kura’s restaurants, they’re all custom-made to avoid this, according to Tanaka. He says he eats many meals at his company’s restaurants.

Photo: Bloomberg

And the sushi dishes are cheap, mostly at 108 yen (95 cents), a price that has barely changed for three decades, even as many of its rivals gradually raise prices.

Tanaka says he keeps the prices low through tight cost control, which goes as far as automating the cleanup process. Finished plates are dropped by customers into a slot at their table, from which they’re transported automatically to the dishwasher and counted to calculate a customer’s bill. This means the company doesn’t need to hire as many waiters or waitresses.

Kura owns 31 patents for inventions it made in developing the restaurants’ unique system. The most-prized one is called Sendo-kun, or Mr Fresh, which is a transparent dome-shaped cover placed on top of each plate of sushi. It flips open when you slightly lift the plate. That way, customers or chefs never need to touch the cap, reducing the risk of germ transmission. Not only that, it contains an embedded chip that lets Kura’s monitoring center keep track of how long a plate has been doing the rounds.

Photo: Bloomberg

US LISTING

Kura currently has more than 420 outlets across Japan, with 19 restaurants in the US and 15 in Taiwan. The stock has risen more than fourfold since the start of 2014, hitting a record in May before tailing off with the broader market.

Tanaka said he wanted to “dream big” when he was growing up in western Japan. With the country reeling from postwar damages, his parents sold goods in the markets to support the family. Tanaka had no interest in pursuing academic goals, so he joined a vinegar company after college. Vinegar is a key ingredient in the rice used as the bed for sushi.

Photo: Bloomberg

He remembers nervously borrowing about three million yen to start the business after his rounds of sushi restaurants convinced him that the model had to change. He recalls being served raw squid in one restaurant and breaking out in a severe rash, finding out later that the squid had been meant for fried dishes, not for serving raw. He couldn’t believe how careless the restaurant had been.

SUPPLY CONTROL

Today, Kura employs 25 people at a monitoring center who work solely on regulating the flow of sushi across its restaurants, using a points system where customers who’ve just arrived get the highest points while those who have been there an hour get zero. “If it’s 100 points in total, we’d offer a certain amount,” Tanaka said. “This is how we control it.”

Kura commands a 20 percent share of Japan’s kaiten sushi market, according to CLSA Ltd. That puts it second after Sushiro Global Holdings Ltd, which has a share of 26 percent, the brokerage says. But while the domestic industry has grown rapidly, commentators say that it’s becoming increasingly mature, creating challenges for firms such as Kura.

“You’re reaching a point where it’s not a saturated market but it may get that way in a couple of years,” said Robert Purcell, an analyst at CLSA in Japan, who rates Kura a buy. “So, will they acquire someone else? You need other growth opportunities.”

Tanaka has said that Kura isn’t looking at domestic M&A. Instead, he’s focusing on overseas growth, betting that Kura’s additive-free food will take off globally amid an increasing consumer trend toward healthy food. The company hopes to add at least 10 restaurants each in the US and Taiwan every year, and to go public in the US as early as 2020. He anticipates bringing Kura to Europe one day, and to also listing shares in Taiwan.

Time will tell whether he succeeds in these plans, but whatever happens, Tanaka has come a long way since his days as a traveling vinegar salesman. At current prices, his family’s stake in Kura is worth hundreds of millions of dollars. But he isn’t content with his success to date.

“I’m not there yet, far from it,” he said, when he’s asked if he feels like he’s realized his dream. “The real show starts now.”

Water management is one of the most powerful forces shaping modern Taiwan’s landscapes and politics. Many of Taiwan’s township and county boundaries are defined by watersheds. The current course of the mighty Jhuoshuei River (濁水溪) was largely established by Japanese embankment building during the 1918-1923 period. Taoyuan is dotted with ponds constructed by settlers from China during the Qing period. Countless local civic actions have been driven by opposition to water projects. Last week something like 2,600mm of rain fell on southern Taiwan in seven days, peaking at over 2,800mm in Duona (多納) in Kaohsiung’s Maolin District (茂林), according to

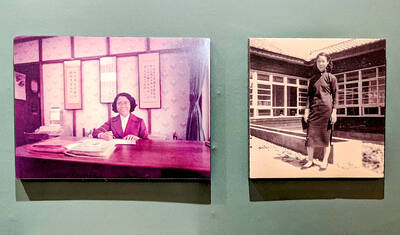

Aug. 11 to Aug. 17 Those who never heard of architect Hsiu Tse-lan (修澤蘭) must have seen her work — on the reverse of the NT$100 bill is the Yangmingshan Zhongshan Hall (陽明山中山樓). Then-president Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) reportedly hand-picked her for the job and gave her just 13 months to complete it in time for the centennial of Republic of China founder Sun Yat-sen’s birth on Nov. 12, 1966. Another landmark project is Garden City (花園新城) in New Taipei City’s Sindian District (新店) — Taiwan’s first mountainside planned community, which Hsiu initiated in 1968. She was involved in every stage, from selecting

The latest edition of the Japan-Taiwan Fruit Festival took place in Kaohsiung on July 26 and 27. During the weekend, the dockside in front of the iconic Music Center was full of food stalls, and a stage welcomed performers. After the French-themed festival earlier in the summer, this is another example of Kaohsiung’s efforts to make the city more international. The event was originally initiated by the Japan-Taiwan Exchange Association in 2022. The goal was “to commemorate [the association’s] 50th anniversary and further strengthen the longstanding friendship between Japan and Taiwan,” says Kaohsiung Director-General of International Affairs Chang Yen-ching (張硯卿). “The first two editions

It was Christmas Eve 2024 and 19-year-old Chloe Cheung was lying in bed at home in Leeds when she found out the Chinese authorities had put a bounty on her head. As she scrolled through Instagram looking at festive songs, a stream of messages from old school friends started coming into her phone. Look at the news, they told her. Media outlets across east Asia were reporting that Cheung, who had just finished her A-levels, had been declared a threat to national security by officials in Hong Kong. There was an offer of HK$1m (NT$3.81 million) to anyone who could assist