Nov. 12 to Nov. 18

The town of Budai (布袋) in Chiayi County was under lockdown in April 1946. Residents had to bribe the quarantine officials to exit the town to buy goods, but when those without money tried to rush the blockade, the police mowed them down with light machine guns.

Chiayi journalist Chung Yi-jen (鍾逸人) retells the scene in his memoir: “Facing starvation, these people risked everything to break through the defenses. Next, the air was filled with gunshot sounds and anguished screams.”

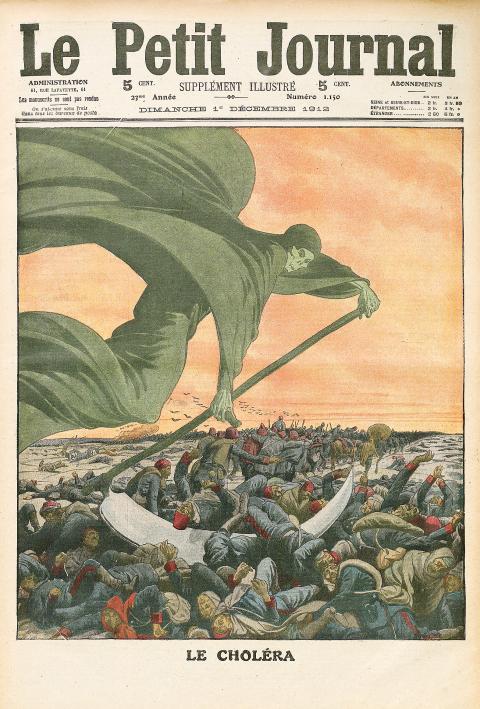

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Chung launched an investigation and published several exposes, but nothing happened to the perpetrators. The blockade was lifted, but it took three months to bring the cholera epidemic under control, with 86 residents dead.

It had been 27 years since the previous cholera outbreak, but the disease made a comeback due to destruction of hospitals during World War II, disintegration of public health infrastructure after the Japanese departed and increased interaction with China after the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) took over Taiwan at the end of World War II. Budai was the earliest to be hit as one of the main ports used by Chinese ships to transport goods to the Chinese Civil War frontlines.

Newspaper reports show that the disease entered Taiwan via a ship from Wenzhou, ravaging southern Taiwan and killing hundreds, including 64 in an Aboriginal village in Taitung County. The outbreak spread north, infecting Yilan by July and emerging in Taipei on Nov. 13, 1946. A total of 2,210 people died nationwide.

Photo: Chang Chung-yi, Taipei TImes

Four other epidemics took place in the 20th century — 1902, 1912, 1919 and 1962. The death rate was extremely high at 82.2 percent for the 1902 bout, surpassing the plague and dysentery, two common diseases. This number dropped to about 61.8 percent over the next three outbreaks, and was down to 6 percent by 1962 due to medical advances. There have only been a handful of cases in recent years — mostly due to consuming tainted foods — with zero deaths.

PESTILENCE ISLAND

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Cholera is believed to have originated in the Indian subcontinent, with the first mass pandemic taking place in 1817 when it spread as far as China and the Mediterranean Sea. Taiwan was highly susceptible to the disease due to its importance in maritime trade, but records are unclear because Qing Dynasty annals often fail to specify the disease that caused an epidemic, according to A Study of Asiatic Cholera in Taiwan During the Japanese Colonial Period by Wei Chia-hung (魏嘉弘).

However, one can deduce that the 1820 “epidemic” in Taiwan was cholera due to the disease ravaging Xiamen, just across the Taiwan Strait, at the exact same time. Using this method, scholars estimate that nine major epidemics took place in Taiwan up to Japanese rule in 1895. Other sources include missionary George Leslie Mackay, who wrote about local treatment of cholera in 1872.

When Japan launched an expedition to Taiwan in 1874 to punish Aborigines, who had killed 54 shipwrecked Japanese sailors, only 12 people died in battle while 550 died due to “disease.” The Qing troops sent from China to deal with the situation didn’t fare any better, with eight or nine people dying per day at the peak of the epidemic. The same thing happened with the French invaders in 1884 — with 34.1 percent of the soldiers succumbing to cholera. Qing reports during this time describe Taiwan as a “land of pestilence.”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Tainan’s iconic Yanshui Beehive Fireworks Festival (鹽水蜂炮) also originated around this time, reportedly in 1885 as residents hoped to chase away cholera through the ritual. However, the disease lingered, with outbreaks in 1888 and 1890 in northern Taiwan.

STRICT COLONIAL MEASURES

The Japanese invaded Penghu in March 1895 to prepare for its takeover of Taiwan. Before they even arrived, 91 soldiers experienced cholera symptoms with 27 dying. This went on for two months before the Japanese were able to control the situation by improving sanitation and sending additional medical help.

During the early days of Japanese rule, their biggest enemy was not the pockets of Taiwanese resistance, but the various diseases that gave rise to the nickname “Island of the Demon Realm” (鬼界之島), according to a Central News Agency report.

The outbreak of 1919 and 1920, which ravaged the entire island except for today’s Nantou and Hualien counties, killed over 5,000 people. Wei writes that while the authorities improved sanitation and put the police in charge of public health, people were mostly uneducated about modern medicine and would often refuse government help.

By 1920, there were four maritime disease inspection centers across Taiwan that meticulously screened each ship coming from epidemic areas, and violators were detained and quarantined. Starting that August, all ships between Japan and Taiwan had doctors on board to conduct inspections before arrival.

On land, the government enforced vaccinations, quarantines, pest control and cleanliness. Public health awareness was heavily promoted through posters, classroom visits and seminars in public places such as temples. Wei’s book contains a popular children’s song from 1920: “People in Taiwan, China and Japan are all afraid of cholera, it enters from the mouth, so don’t drink untreated water and eat raw food, exterminate flies when you see them…”

Wei writes that after people found that the vaccine was effective, distrust toward the government began to dissipate.

GONE FOR GOOD

The KMT was able to bring the 1946 situation under control with the help from the UN Relief and Rehabilitation Administration. The 1962 epidemic originated in Indonesia and spread to Taiwan via the Philippines, which reported over 10,000 infected due to lax disease control measures, according to A Study of the Para-Cholera Outburst in Taiwan in 1962 (1962年台灣副霍亂大流行之研究) by Chen Yu-lun (陳喻倫).

Chen writes that since this was a subtype of cholera, many countries, including Taiwan, did not treat it as cholera proper. Up until the WHO’s emergency meeting in the Philippines in April 1962, Taiwan had not inspected any visitors from infected countries, as it was not required for this type of cholera. This incident greatly affected Taiwan’s economy, especially agricultural exports, and sparked much criticism toward the government’s efforts in public health and disease control. Yen Chun-hui (顏春輝), director of the now-defunct Public Health Department, stepped down.

The government started to take a more proactive approach to disease control, working closely with the US-funded Provincial Institute of Environmental Sanitation, training local personnel and building more infrastructure such as improved wells, running water and modern bathrooms in villages across Taiwan.

Eventually, not only cholera was eradicated. Gastrointestinal diseases were the top causes of death in Taiwan in the 1950s, but by 1965 they had receded to seventh place.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

May 26 to June 1 When the Qing Dynasty first took control over many parts of Taiwan in 1684, it roughly continued the Kingdom of Tungning’s administrative borders (see below), setting up one prefecture and three counties. The actual area of control covered today’s Chiayi, Tainan and Kaohsiung. The administrative center was in Taiwan Prefecture, in today’s Tainan. But as Han settlement expanded and due to rebellions and other international incidents, the administrative units became more complex. By the time Taiwan became a province of the Qing in 1887, there were three prefectures, eleven counties, three subprefectures and one directly-administered prefecture, with

President William Lai (賴清德) yesterday delivered an address marking the first anniversary of his presidency. In the speech, Lai affirmed Taiwan’s global role in technology, trade and security. He announced economic and national security initiatives, and emphasized democratic values and cross-party cooperation. The following is the full text of his speech: Yesterday, outside of Beida Elementary School in New Taipei City’s Sanxia District (三峽), there was a major traffic accident that, sadly, claimed several lives and resulted in multiple injuries. The Executive Yuan immediately formed a task force, and last night I personally visited the victims in hospital. Central government agencies and the

Among Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) villages, a certain rivalry exists between Arunothai, the largest of these villages, and Mae Salong, which is currently the most prosperous. Historically, the rivalry stems from a split in KMT military factions in the early 1960s, which divided command and opium territories after Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) cut off open support in 1961 due to international pressure (see part two, “The KMT opium lords of the Golden Triangle,” on May 20). But today this rivalry manifests as a different kind of split, with Arunothai leading a pro-China faction and Mae Salong staunchly aligned to Taiwan.

As with most of northern Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) settlements, the village of Arunothai was only given a Thai name once the Thai government began in the 1970s to assert control over the border region and initiate a decades-long process of political integration. The village’s original name, bestowed by its Yunnanese founders when they first settled the valley in the late 1960s, was a Chinese name, Dagudi (大谷地), which literally translates as “a place for threshing rice.” At that time, these village founders did not know how permanent their settlement would be. Most of Arunothai’s first generation were soldiers