As with most of northern Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) settlements, the village of Arunothai was only given a Thai name once the Thai government began in the 1970s to assert control over the border region and initiate a decades-long process of political integration. The village’s original name, bestowed by its Yunnanese founders when they first settled the valley in the late 1960s, was a Chinese name, Dagudi (大谷地), which literally translates as “a place for threshing rice.”

At that time, these village founders did not know how permanent their settlement would be. Most of Arunothai’s first generation were soldiers in the KMT’s rearguard units in China’s Yunnan province, who at the end of the Chinese Civil War were unable to retreat with the main body of Chiang Kai-shek’s (蔣介石) forces to Taiwan.

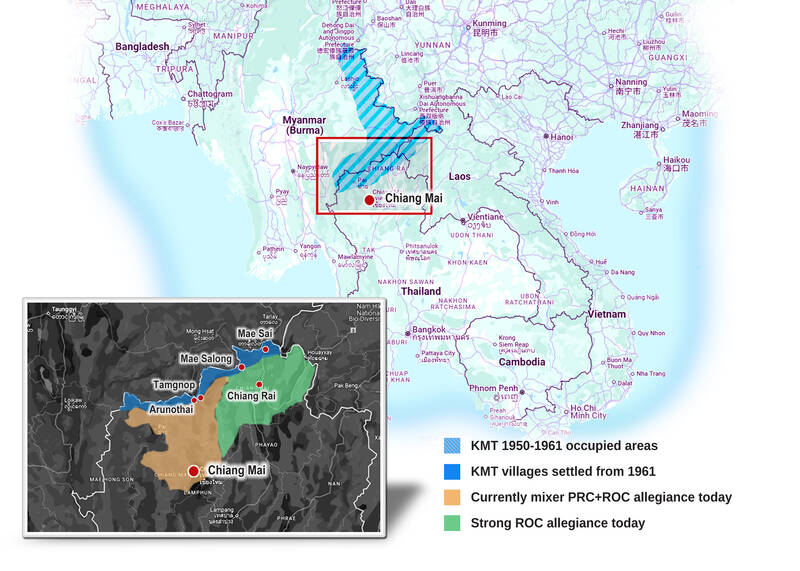

Instead, they fled across China’s southern border, where through the 1950s and 1960s they eked out a precarious existence in the foreboding terrain of the mountains straddling Burma’s Shan State and northern Thailand. There, the KMT’s 3rd and 5th armies regrouped as the “Yunnan Province Anti-Communist National Salvation Army.”

GRAPHIC: Angela Chen

Between 1950 and 1952, they launched at least seven incursions into Yunnan province but in every instance were repelled by communist units. Officially, they served under the Taipei command of Chiang Kai-shek, who believed he would one day retake the Chinese mainland and insisted on keeping the KMT units as a spearhead on Mao Zedong’s (毛澤東) southern flank. With the help of the CIA, Chiang continued to resupply the troops with arms into at least the early 1960s.

OPIUM TO FIGHT THE COMMUNISTS

But airlifts alone could not finance this guerrilla army. During the 1950s, the KMT units turned for survival to the drug trade, transporting opium from the Burmese highlands to the plains of northern Thailand in mule caravans often a mile long. They also taxed other opium traders moving through their lands and, from the 1960s, operated their own heroin refineries. By 1973, according to American historian Alfred McCoy, it was estimated that KMT units controlled about 90 percent of the opium coming out of Burma and almost one third of the world’s total illegal opium supply.

Photo: David Frazier

“We have to continue to fight the evil of Communism, and to fight you must have an army, and an army must have guns and to buy guns you must have money. In these mountains the only money is opium,” General Tuan Hsi-wen (段希文), leader of the KMT’s 5th army, famously told a British journalist in 1967.

Though KMT armies chiefly saw opium as a means of survival, their heroin fueled the epidemic of addiction that plagued US troops then fighting in nearby Vietnam and propelled to infamy the opium-growing highlands they controlled. Dubbed the “Golden Triangle” in a 1971 report by the US Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), the three-way border region between Thailand, Myanmar and Laos has carried this dark legacy to the present day.

Though the KMT armies in Thailand exited the drug trade in the 1980s, Burmese soldiers they trained like Kun Sha and Lo Hsing-han (羅星漢) took over as next generation drug warlords. Even now, rebel militias in Myanmar — which once again last year ranked as the world’s largest illegal producer of opium — continue to fund themselves through the drug trade.

Photo: David Frazier

The KMT troops began settling in Thailand in the early 1960s. As the Communist bloc vied with the West to carve up Southeast Asia during the Cold War, Soviet-led protests in the UN charged that the KMT troops were an illegal invading force. Negotiations involving Burma, Thailand, the US and Taiwan resulted in two waves of withdrawals. Any refugees who elected to remain were told to vacate Burma — which was officially neutral though supported by the Soviet Union — and resettle in Thailand, a US ally.

Chiang repatriated 5,000 soldiers to Taiwan in 1953 and then 7,000 more in 1961 — though it was later shown that some of these evacuees were refugees rather than soldiers. This may have been an intentional subterfuge. With each airlift, Chiang sent secret orders for key generals to stay behind with a few thousand crack troops to remain as a vanguard force on China’s underbelly.

Another condition of the withdrawals was that Taiwan terminate its military support — even Thailand did not want foreign armies on its soil. The second repatriation thus included removal of the army’s commanding general, Li Mi (李彌).

Photo: David Frazier

At this time, the vestiges of the KMT Yunnan armies consisted of roughly 3,500 troops, who were now officially stateless. It was at this moment that the Taiwanese press gave this KMT force the name by which they are still remembered today — “the Lost Army.”

Without General Li Mi’s unifying force, the army split into two factions, the 3rd army under the command of General Lee Wen-huan (李文煥) and the 5th army under General Tuan. Both generals established camps in remote and easily defensible mountain outposts — Li at Tam Gnop and Tuan at Mae Salong. For the opium mule caravans that continued to flow from Burma, these camps quickly became the respective gateways to Thailand’s Chiang Mai and Chiang Rai provinces.

COLD WAR NETWORKS

At Tam Gnop, General Lee’s residence along with some military base facilities are still preserved today as a private museum. Set behind low brick walls and heavy wooden doors, Li’s courtyard home is a sanctuary of rose bushes and tropical flowers.

Li initially christened this camp, a mountaintop aerie at about 1,300 meters in altitude, with the Chinese name Tang Wo (唐窩), meaning “nest of the Tang” or “nest of the Chinese.”

A small conference room with 1970s upholstered wicker sofas around a leopardskin coffee table displays photos of Li in meetings with Thai generals of the day, who flew by helicopter to negotiate the KMT army’s role as a border guard force. One shot shows Li and other KMT military commanders, all wearing business suits, in Taiwan with Chiang Kai-shek.

There, I met Lee’s eldest daughter, Lee Jianyuan (李健圓), a chirpy, pleasant woman with a graying, windswept perm. Speaking graceful Mandarin, she recounted, “My father was always on the go, always traveling, to Bangkok, Taiwan, Hong Kong, everywhere.”

During the height of the Cold War, as Mao’s cultural revolution of 1966 to 1976 shuttered China’s universities, sent intellectuals to hard labor in the countryside and banned all art save that of the Communist Party, these cosmopolitan cities became the guardians of not only traditional Chinese culture but also the producers of a new Chinese pop culture. KMT generals mixed with the new transnational Chinese elite.

“In Hong Kong, he was friends with the Shaw Brothers, the bosses of the famous movie studio,” Lee continued. “They would give him prints of their new films to bring back here and screen for the troops.”

By the late 1960s, the Thai government began a process by which the KMT’s Lost Army factions would over the following decade abandon the drug trade and disarm, at least outwardly. (General Lee continued to secretly traffic in opium and heroin into the 1980s.)

A deal was struck by which KMT units were deputized as a paramilitary unit of the Thai army and sent to root out a Hmong communist insurgency spilling over from Laos. Upon the successful completion of this mission, the KMT soldiers were rewarded with Thai citizenship. Thai authorities did not however extend citizenship privileges to the entire Yunnan diaspora, and even today, some are unable to apply for national ID cards.

It was also around the end of the 1960s that some of General Lee’s soldiers at Tam Gnop began to descend via steep, winding mountain paths to a fertile valley a few kilometers to the west — Arunothai.

A NEW SCHOOL

Within a year of the town’s founding, the Huaxing School was established in a simple thatched hut lit by kerosene lamps. Soon after, the school began to receive assistance from the Free China Relief Association, a charity founded in Taiwan by Madame Chiang Kai-shek, the wife of the Generalissimo, and others to support refugees fleeing China.

Madame Chiang (宋美齡), who’d been educated in an American finishing school and spoke English with a lilting southern drawl, had played a key role in trying to secure US political support for the Chinese Nationalist war effort in the 1930s and 1940s. After the KMT’s retreat, she took charge of numerous charities.

By 1979, the Huaxing School had more than 600 students and won its first direct grant from the KMT government in Taiwan, which provided it with funds for a new schoolhouse.

The school has since grown to become southeast Asia’s largest school for overseas Chinese. Though it maintains a staunch loyalty to Taiwan, China has over the past two decades aggressively contested that loyalty through enticements of financial assistance and by supporting a former Huaxing principal to establish a competing, China-aligned school in the same village. (See part one on May 15.)

Arunothai and dozens of other Yunnan villages, especially in Thailand’s Chiang Mai and Mae Hong Son provinces, have now become divided in their relations between China and Taiwan, with at least 44 village schools switching over to China’s system.

One Thai province, Chiang Rai, has however remained stalwart in its links to Taiwan. Its key village of Mae Salong will be the subject of part three in this series.

This is part two in a five-part series on Thailand’s Chinese diaspora and its shifting relationships between Taiwan and China.

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

On a harsh winter afternoon last month, 2,000 protesters marched and chanted slogans such as “CCP out” and “Korea for Koreans” in Seoul’s popular Gangnam District. Participants — mostly students — wore caps printed with the Chinese characters for “exterminate communism” (滅共) and held banners reading “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party” (天滅中共). During the march, Park Jun-young, the leader of the protest organizer “Free University,” a conservative youth movement, who was on a hunger strike, collapsed after delivering a speech in sub-zero temperatures and was later hospitalized. Several protesters shaved their heads at the end of the demonstration. A

Every now and then, even hardcore hikers like to sleep in, leave the heavy gear at home and just enjoy a relaxed half-day stroll in the mountains: no cold, no steep uphills, no pressure to walk a certain distance in a day. In the winter, the mild climate and lower elevations of the forests in Taiwan’s far south offer a number of easy escapes like this. A prime example is the river above Mudan Reservoir (牡丹水庫): with shallow water, gentle current, abundant wildlife and a complete lack of tourists, this walk is accessible to nearly everyone but still feels quite remote.

In August of 1949 American journalist Darrell Berrigan toured occupied Formosa and on Aug. 13 published “Should We Grab Formosa?” in the Saturday Evening Post. Berrigan, cataloguing the numerous horrors of corruption and looting the occupying Republic of China (ROC) was inflicting on the locals, advocated outright annexation of Taiwan by the US. He contended the islanders would welcome that. Berrigan also observed that the islanders were planning another revolt, and wrote of their “island nationalism.” The US position on Taiwan was well known there, and islanders, he said, had told him of US official statements that Taiwan had not