“Having come all this way, I’d rather pay to get in, and really learn something about the way people lived back then.”

So said Vincent Mattsson, a Swedish tourist I met outside the Lu Jing-tang Residence (盧經堂厝) in Tainan City’s Anping District (安平). Of the 10 days he was staying in Taiwan, he planned to devote two to places of historic and cultural importance in Tainan.

There is no admission charge at the Lu Jing-tang Residence, and after twice looking around this single-story building — completed circa 1902 and opened to the public in 2014 — I could see what Mattson was driving at.

Photo: Steven Crook

A trilingual information panel out front informs visitors that Lu Jing-tang (盧經堂) dealt in sugar and kerosene, owned warehouses nearby and that this residence-cum-office faced the harbor. (Due to land reclamation, the nearest wharf is now 300m away.)

“Which room was his office?” Mattson asked me. “It would be nice to know the function of each part of the building, but half of it’s a shop.”

He was referring to an outlet of Dagang Herb Dream House (大港香草夢工坊), which sells handmade lotions and insect repellents. The business is being incubated by Dagang Community Development Association in Dagang Li (大港里), a mere 3km inland from Anping. When I told him later via e-mail that it was an ultra-local social enterprise, he responded: “Better than renting the space to a multinational corporation, of course.”

Photo: Steven Crook

The next line of Mattson’s e-mail caught me by surprise. “Since getting home, I’ve been thinking about the toilet there.”

There was nothing wrong with the purpose-built toilet block next to the residence, he wrote. Instead, he was wondering where the building’s inhabitants had washed themselves, there being no obvious bathroom in the original structure. “Did they go down to the harbor… That’s what I mean about understanding lifestyles long ago. Is no one else curious?”

People who do not live in Tainan have to pay NT$50 to enter Fort Zeelandia (安平古堡), the main Dutch base in the mid-17th century. For their money, tourists do get a pretty good museum. It covers, among other things, aspects of the fort’s construction, items of pottery uncovered by archaeologists and the fate of Frederick Coyett, the governor who surrendered the fort to Koxinga in 1662.

Photo: Steven Crook

Nonetheless, some foreign visitors have come away feeling a little disappointed by the lack of information available at the fort. Michael Booth, author of The Meaning of Rice, went there earlier this year for a book about East Asia he is writing.

“As I’ve been researching the history of Taiwan, it occurs to me that places like the fort are of incredible historic value, not just for Taiwan, but for the world’s heritage,” the British travel/food writer told me via e-mail. “Their history is the history of colonialism and global trade in East Asia which is the history of China, of Korea, of Japan and directly connects with what is happening in the region today. I really enjoyed the festive atmosphere at Anping when I visited, but was a little in the dark regarding the site’s history. I think the two can live together, it’s just a question of good curating and management.”

Hoping to get an official perspective on the issue of “free entry to a commercialized space” versus “historical authenticity at a price” I contacted Tainan City Government Cultural Affairs Bureau. The bureau not only manages the Lu Jing-tang Residence and more than a dozen other relics around the city, but also funded the renovation effort earlier this decade that transformed the residence from a near-ruin to a highly photogenic landmark.

Photo: Steven Crook

I wanted to know if budgetary pressure is a decisive factor. Having learned from Chinese-language blogs that there used to be a NT$50 admission fee for the Lu Jing-tang Residence, I wondered if the bureau had found that people are unwilling to pay to see such places. Without rental income from souvenir stores and coffee-shops, perhaps some of these buildings cannot be maintained and kept open.

The bureau never responded, but I made return visits to other Anping attractions that now cost nothing to enter.

Taiwan’s defunct salt industry intrigues quite a few Western visitors, but they will not learn much about it at Sio House (夕遊出張所), 500m west of Fort Zeelandia.

Photo: Steven Crook

The 96-year-old single-story timber building was originally a workplace for clerks assigned to the Monopoly Bureau of the Governor-General of Taiwan, a branch of the Japanese colonial authorities that controlled trade in alcohol, tobacco, camphor, matches, opium and petroleum, as well as salt. After World War II, it became a staff dormitory for salt-industry administrators — and that is about all that can be learned on-site.

The interior is organized with one end in mind: The sale of salt and salt-themed gifts. Dishes of colored salt, one for each day of the year, catch the visitor’s eye, and staff explain how the color reflects the personality of those born on that day. It would be quite easy to come here and never notice the replica-in-salt of the National Palace Museum’s Jadeite Cabbage. Massively larger than the original, it is remarkable in its own way, and deserves a much more obvious location.

Haishan Hall (海山館) is far older, dating from just after Taiwan’s annexation into the Qing Empire, and has not been commercialized in the same way as Sio House. It is more of an art gallery than anything else, yet some inexpensive and unrelated gewgaws are offered for sale.

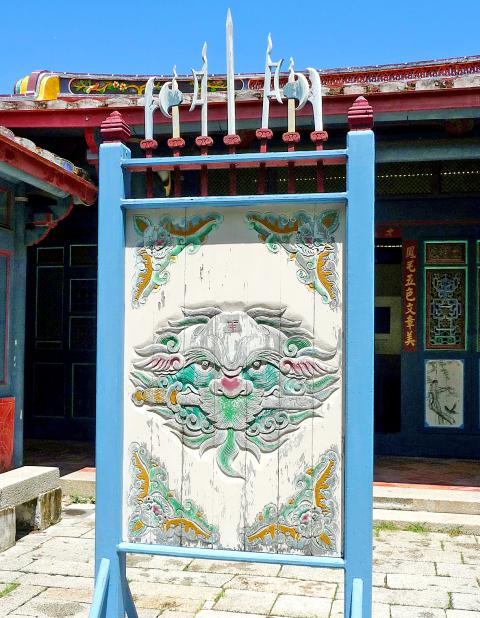

Photo: Steven Crook

My half-empty glass view is that Taiwan does not lack for places to shop or drink coffee, and that historic sites which have survived into the 21st century should be, above all, places of enlightenment and beauty.

At the same time, I acknowledge that the desire to preserve tangible antiquity in Taiwan is stronger than ever before. In the early 1990s, I noticed several derelict yet impressive buildings, and assumed they would eventually be replaced with something more useful but less alluring. I am glad my pessimism was proved wrong in the cases of Tainan’s Hayashi Department Store (林百貨) and Xinhua Butokuden (新化武德殿). Filling the former with shops is in keeping with its history, obviously. The latter is once again a place where youngsters practice martial arts — which just goes to show that rescuing an old building need not involve selling its soul.

Steven Crook has been writing about travel, culture, and business in Taiwan since 1996. Having recently co-authored A Culinary History of Taipei: Beyond Pork and Ponlai, he is now updating Taiwan: The Bradt Travel Guide.

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,