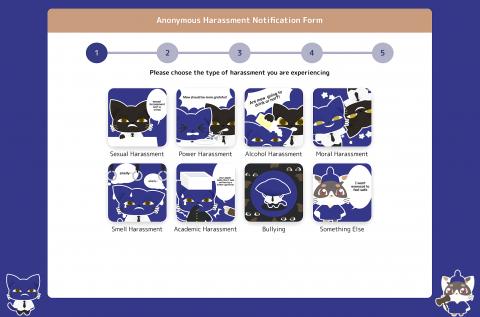

A cartoon cat in a purple robe brandishes a tiny gavel as it comforts another cat yowling from abuse: The images welcoming visitors to Sorehara, a Japanese Web site for anonymous complaints about harassment and other grievances, are deceptively endearing.

“You don’t have to suffer alone. Get help from the cat who seeks justice,” it says.

Sorehara, an abbreviation of the Japanese for “That’s harassment,” was devised by a 21-year-old college student and, like many #MeToo apps and Web sites, is meant to help victims of abuse safely fight back against their tormentors.

Photo: AP

It allows users to send anonymous complaints by e-mail, without registering any personal information and is gaining popularity in Japan, despite some concerns over the potential for its misuse.

On-the-job harassment is gaining attention as the #MeToo movement slowly takes root here. Sexual harassment claims have brought on recent resignations of high-profile officials, pop stars and professors.

JAPANESE EXTREMES

But the Web site doesn’t focus just on sexual misbehavior. Sorehara goes to very Japanese extremes in allowing users to register their disapproval electronically to those who offend them in all sorts of ways, including indulging in garlic, wearing excessive perfume or smelling too strongly of cigarette smoke.

Victim blaming can be severe in highly conformist Japan so anonymity is essential for helping them feel safe, says Tatsuki Yoshida, 21, who developed Sorehara and founded his start-up Quaerere last year.

“In Japan, companies don’t like to deal with harassment issues. People who raise their voices about harassment usually just get moved to a different department or maybe given a raise. Or they get fired,” he said in a recent interview in Fujisawa, southwest of Tokyo.

A college sophomore, he is taking time off from his studies to work on Sorehara.

Inappropriate behavior and unwanted sexual advances, repugnant and dangerous as they can be, are just part of a universe of gripes people might have about their co-workers.

So Sorehara offers users various options, including “power harassment,” bullying, alcohol harassment, sexual harassment and even “smell harassment.”

Next, they choose the level of severity, ranging from mere annoyance to threatening legal action. They fill in the e-mail and a name or nickname of the person accused of the misbehavior, but not their own e-mail or name. The Japanese-language site gives an option to delay sending the message for up to two months, to reduce the possibility of the accuser being recognized.

Recipients get an e-mail politely notifying them of the harassment claim, asking if they recognize it and providing a choice of responses such as: “I will reflect on my behavior,” or “I have done nothing wrong.”

DEALING WITH HARRASSMENT

An English version was released recently, and a Korean-language version is in the works.

The #MeToo era has inspired companies, colleges and support groups to devise all sorts of apps and other online support for victims of sexual harassment and other abuses.

Some, like Protibadi in Bangladesh, HarassMap in Egypt and bSafe use mapping and GPS technology to help protect people by identifying potentially unsafe locations or notifying a user’s friends if the person seems to be in trouble. AI-powered chatbots like Spot, developed in California, automate harassment reporting. Others focus on support and counseling for victims. Few combine anonymity with direct online complaints the way Sorehara does.

Some worry that this anonymity could invite abuse because the claims can’t be verified, and because many Japanese tend to view simple annoyances like body odor as grievous social transgressions.

“There’s a possibility that the person you say is a harasser is not really harassing,” said Yoko Iwasaki of Cuore C Cube Co., a business management consulting company in Tokyo that focuses on harassment and diversity issues.

“That person who receives that email from Sorehara might feel very weird and attacked. Sending that kind of message can also be harassment,” she said.

But Hiroaki Morio, a professor at Kansai University, says he just believes the Web site is meant to be “light-hearted.”

“They’re trying to make harassment easier to deal with,” Morio said.

OPEN COMMUNICATION LINES

Despite the wider recognition of sexual harassment as a problem, Japanese thinking has not changed much and as most people still feel unable to speak up, so anonymous outlets like Sorehara can help, says Mayumi Haruno, who became the first Japanese woman to sue alleging on-the-job sexual harassment after she was forced out of her job in the 1980s. She won 1.65 million yen (US$15,000) in damages in a lawsuit that she filed in 1989.

Social media that allow anonymity, like Line, Twitter and Mixi are popular in Japan and in neighboring South Korea, where Blind, an anonymous message board app for employees, launched a #MeToo message board early this year.

“I think people are still afraid to make things public because they’re afraid of a backlash,” said Kyum Kim, co-founder of TeamBlind, which started the Blind app in 2013 and has offices in San Francisco, Seoul and Tokyo. “I think that’s the culture right now in Japan and Korea.”

Sorehara says it sends about 50 complaints a day. Most people who get them accept or at least acknowledge them, suggesting most claims are genuine, Yoshida said.

He says Sorehara is meant more to open lines of communication and raise awareness than to provide a formal way to report or solve harassment cases. Different people draw social lines in different places, Yoshida says, so he wants Sorehara to help people educate each other.

Several companies, including one with about 200 employees, are working with Sorehara to use the service internally, and Yoshida says he is also collaborating with counseling services.

“I don’t think companies are really changing internally,” Yoshida said. “But they are scared about their image, so at least they are paying more attention.”

June 23 to June 29 After capturing the walled city of Hsinchu on June 22, 1895, the Japanese hoped to quickly push south and seize control of Taiwan’s entire west coast — but their advance was stalled for more than a month. Not only did local Hakka fighters continue to cause them headaches, resistance forces even attempted to retake the city three times. “We had planned to occupy Anping (Tainan) and Takao (Kaohsiung) as soon as possible, but ever since we took Hsinchu, nearby bandits proclaiming to be ‘righteous people’ (義民) have been destroying train tracks and electrical cables, and gathering in villages

Swooping low over the banks of a Nile River tributary, an aid flight run by retired American military officers released a stream of food-stuffed sacks over a town emptied by fighting in South Sudan, a country wracked by conflict. Last week’s air drop was the latest in a controversial development — private contracting firms led by former US intelligence officers and military veterans delivering aid to some of the world’s deadliest conflict zones, in operations organized with governments that are combatants in the conflicts. The moves are roiling the global aid community, which warns of a more militarized, politicized and profit-seeking trend

The wide-screen spectacle of Formula One gets a gleaming, rip-roaring workout in Joseph Kosinski’s F1, a fine-tuned machine of a movie that, in its most riveting racing scenes, approaches a kind of high-speed splendor. Kosinski, who last endeavored to put moviegoers in the seat of a fighter jet in Top Gun: Maverick, has moved to the open cockpits of Formula One with much the same affection, if not outright need, for speed. A lot of the same team is back. Jerry Bruckheimer produces. Ehren Kruger, a co-writer on Maverick, takes sole credit here. Hans Zimmer, a co-composer previously, supplies the thumping

Dr. Y. Tony Yang, Associate Dean of Health Policy and Population Science at George Washington University, argued last week in a piece for the Taipei Times about former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) leading a student delegation to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) that, “The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world” (“Ma’s Visit, DPP’s Blind Spot,” June 18, page 8). Yang contends that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has a blind spot: “By treating any