As a university student, Luna Atmowijoyo prayed five times a day, refused to shake hands with men who weren’t relatives and was “more fundamentalist” than her pious Muslim parents.

But a decade later, Atmowijoyo has turned her back on Islam and is among a small number of atheists in Indonesia who live in fear of jail or violent reprisals from religious hardliners.

Leading a double life — devout Muslim on the outside, non-believer on the inside — is often the only choice for atheists in the world’s biggest Muslim majority country.

Photo: AFP

Atmowijoyo, who lives with her parents, still wears an Islamic headscarf to escape the wrath of an abusive father who knows nothing of his daughter’s change of heart, which started when she was told to avoid friendships with non-Muslims.

“A lot of simple things started to bother me,” said the 30-year-old, who asked AFP not to use her real name.

“Like I couldn’t say Merry Christmas or Happy Waisak to people of other religions,” she added, referring to a Buddhist holiday also known as Vesak or Buddha’s Birthday in other parts of Asia.

Photo: Reuters

Treating gay people as abnormal was another problem and it soon became impossible for Atmowijoyo — once a conservative Islamic party member — to square the Quran’s teachings with science.

Then the unthinkable crept into her mind: God does not exist.

BLASPHEMY

Photo: EPA

The sprawling Southeast Asian archipelago is officially pluralist with six major religions recognized, including Hinduism, Christianity and Buddhism, while freedom of expression is supposed to be guaranteed by law.

But criticizing religion — particularly Islam, which is followed by nearly 90 percent of Indonesia’s 260 million citizens — can land you in jail.

This year, a university student was charged for a Facebook post that compared Allah to the Greek gods and said the Quran was no more scientific than the Lord of the Rings. He faces up to five years in prison.

Alexander Aan was jailed for 30 months in 2012 for posting explicit material about the Prophet Mohammed online and declaring himself an atheist.

The prosecutions fit a wider trend of discrimination against the archipelago’s sizable population of minorities, observers said.

Authorities, however, insist atheist beliefs are not illegal — as long as they’re not aired in public.

“Once somebody disseminates that idea, or the concept of atheism, that will be problematic,” said Abdurrahman Mas’ud, head of the research and development agency at the Ministry of Religion.

‘FEAR FOR MY LIFE’

Two decades after the fall of dictator Suharto — who kept the country running along secular lines — conservative Islam has exploded into Indonesia’s public life in lockstep with the rise of hardliners and religiously motivated violence.

The country has grappled with Islamist militancy for years, including the 2002 Bali bombing that killed more than 200 in Indonesia’s worst-ever terror attack.

More attacks followed and this year, 13 people were killed in a wave of suicide bombings claimed by the Islamic State group that targeted Christian congregations.

Buddhist temples have also been attacked, while this year an angry mob rampaged through a small community of the Ahmadiyya Islamic minority on the island of Lombok, destroying homes and forcing dozens of members to flee.

Atheists interviewed said they worried that hardliners, encouraged by populist politicians, could turn their attention to them next.

“The worst thing that can happen in Indonesia is we can be killed,” said one 35-year-old graphic designer who was raised as a Catholic. “I genuinely fear for my life.”

Many apostates — particularly those from conservative Muslim backgrounds — assume two identities, like Atmowijoyo.

“As long as they keep quiet there is not much risk,” said Timo Duile, a researcher at the University of Bonn who has studied atheism in Indonesia. “That is the reason that most atheists I talked to prefer to stay incognito.”

INCLUSIVE ISLAM?

No one knows how many atheists there are in Indonesia.

While small groups hold regular meetings in large cities, most have sought out like-minded individuals online.

The “You Ask, Atheists Answer” open forum on Facebook has nearly 60,000 members, and there are more like it online.

Karina, based in Singapore, said when she found a private Facebook page for fellow atheists in her native Indonesia she finally felt she was “not alone.”

Atheists interviewed said they worried about doxxing — publishing private information to identify users — by radical Islamist cyber groups, which regularly make death threats.

Indonesia is not the only Muslim-majority nation where non-believers face danger.

Secular and atheist bloggers have been killed in Bangladesh, atheists have been threatened by government officials in Malaysia and jailed in Egypt.

Indonesia, by contrast, is often praised for its moderate, inclusive brand of Islam — but that is something many atheists say is no longer a reality.

Karina said she was concerned about friends back home. “I’m quite worried about them.”

And even in Singapore, she felt she needed to watch her back.

“I’m becoming more careful. I still post some critiques about Islam, but now it is more subtle.”

The Taipei Times last week reported that the rising share of seniors in the population is reshaping the nation’s housing markets. According to data from the Ministry of the Interior, about 850,000 residences were occupied by elderly people in the first quarter, including 655,000 that housed only one resident. H&B Realty chief researcher Jessica Hsu (徐佳馨), quoted in the article, said that there is rising demand for elderly-friendly housing, including units with elevators, barrier-free layouts and proximity to healthcare services. Hsu and others cited in the article highlighted the changing family residential dynamics, as children no longer live with parents,

It is jarring how differently Taiwan’s politics is portrayed in the international press compared to the local Chinese-language press. Viewed from abroad, Taiwan is seen as a geopolitical hotspot, or “The Most Dangerous Place on Earth,” as the Economist once blazoned across their cover. Meanwhile, tasked with facing down those existential threats, Taiwan’s leaders are dying their hair pink. These include former president Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文), Vice President Hsiao Bi-khim (蕭美琴) and Kaohsiung Mayor Chen Chi-mai (陳其邁), among others. They are demonstrating what big fans they are of South Korean K-pop sensations Blackpink ahead of their concerts this weekend in Kaohsiung.

Taiwan is one of the world’s greatest per-capita consumers of seafood. Whereas the average human is thought to eat around 20kg of seafood per year, each Taiwanese gets through 27kg to 35kg of ocean delicacies annually, depending on which source you find most credible. Given the ubiquity of dishes like oyster omelet (蚵仔煎) and milkfish soup (虱目魚湯), the higher estimate may well be correct. By global standards, let alone local consumption patterns, I’m not much of a seafood fan. It’s not just a matter of taste, although that’s part of it. What I’ve read about the environmental impact of the

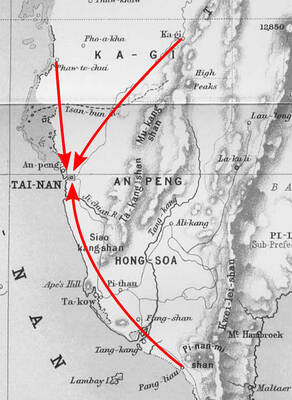

Oct 20 to Oct 26 After a day of fighting, the Japanese Army’s Second Division was resting when a curious delegation of two Scotsmen and 19 Taiwanese approached their camp. It was Oct. 20, 1895, and the troops had reached Taiye Village (太爺庄) in today’s Hunei District (湖內), Kaohsiung, just 10km away from their final target of Tainan. Led by Presbyterian missionaries Thomas Barclay and Duncan Ferguson, the group informed the Japanese that resistance leader Liu Yung-fu (劉永福) had fled to China the previous night, leaving his Black Flag Army fighters behind and the city in chaos. On behalf of the