May 14 to May 20

The Taiwanese politicians did not know who they were welcoming when they arrived at Songshan Airport on May 14, 1965 under the orders of the Ministry of National Defense and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) headquarters.

When they found out who it was, some were overjoyed, others were stunned into silence: how could they be greeting a “traitor” with such fanfare? But orders were orders.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Nearby, a Government Information Office official gathered the reporters on site, loudly announcing: “Thomas Liao (廖文毅) has abandoned his Taiwanese independence activities in Japan. He has renounced his evil ways and has returned home to swear his allegiance to his nation.”

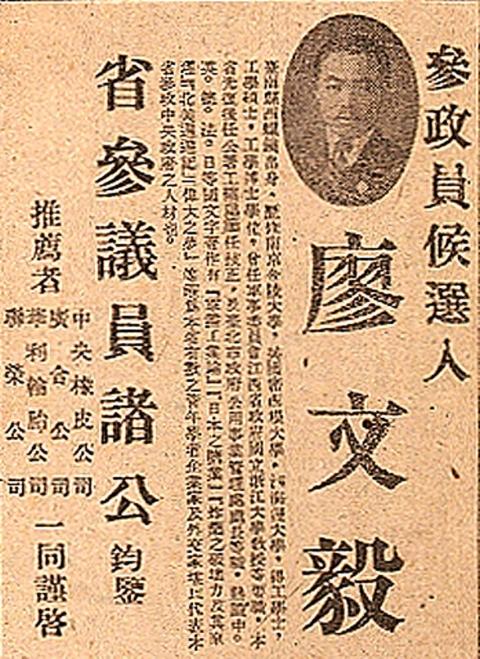

The journalists, many of whom had never heard of Liao, scrambled to dig up information about him. They finally learned from the politicians on site about the Taiwanese government-in-exile in Japan. Liao was its president.

FULL CIRCLE

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“To Taiwanese, Thomas Liao was a hot topic in politics from the mid-1940s to mid-1960s,” writes Lee Shih-chieh (李世傑) in his book, Account of the Surrender of President Thomas Liao (大統領廖文毅投降始末). “But by the late 1960s, he was a tragic character that had faded into obscurity.”

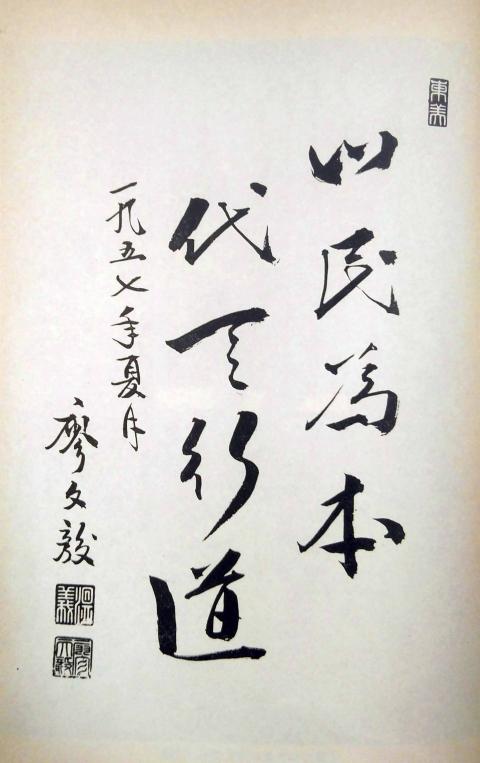

This fall coincided with Liao’s surrender to the KMT, which brought him full circle after serving as a KMT official in 1945 following the surrender of Japan. At first, Liao welcomed the KMT, thinking that good days were ahead now that the colonizers were defeated. But like many Taiwanese, he quickly grew disillusioned with government misrule.

In January 1947, the US-educated Liao published an article in Pioneer (前鋒) magazine, proposing a Federated States of China within which Taiwan could enjoy complete autonomy.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

He did not intend to flee Taiwan, but the 228 Incident, an uprising that began on Feb. 27, 1947, against the then-KMT authoritarian regime, broke out when he was visiting Shanghai, and the local authorities blamed the anti-government uprising on Liao and his brother. His brother was arrested while Liao fled to Hong Kong, becoming a fugitive exiled from his homeland.

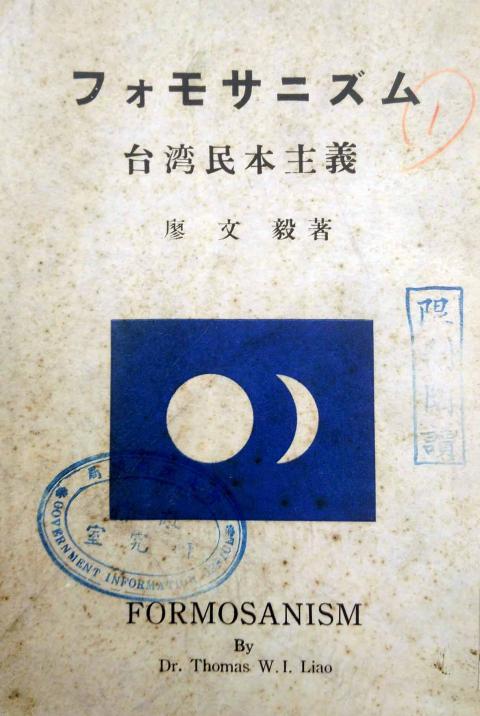

He was still insistent on the Federated States idea when he established the Formosan League for Reemancipation (台灣再解放聯盟) on the anniversary of the 228 Incident, but cofounder Huang Chi-nan (黃紀男) claims to have convinced him that independence was the only road after a series of arguments.

Liao moved to Japan in 1950 to continue his crusade. On the ninth anniversary of the 228 Incident in 1956, he established the Republic of Taiwan Provisional Government (台灣共和國臨時政府) and installed himself president.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Liao’s defiant attitude took a sharp turn in 1965. Before he boarded the flight back to Taiwan, he made the following official statement in Tokyo: “I, Thomas Liao have been working for the interests and happiness of the Taiwanese people overseas for almost 20 years … But now I recognize from the bottom of my heart that the biggest threat is the infiltration and subversion by the Chinese Communists. Thus, I have renounced my Taiwanese independence activities and have decided to answer the call from President Chiang’s (Kai-shek, 蔣介石) Anti-Communist Union, and hereby pledge to do everything within my power to fight for the great cause of defeating the Communists.”

DOWNFALL

Lee writes that the KMT did not see Liao as a big threat until late 1955 when they came across a flyer from Japan pronouncing the establishment of a Taiwan Provisional National Assembly. They scrambled for information, and when Liao pronounced himself president the next year, it was clear that this was high treason. Unable to obtain information from Japan, the KMT sent agents to Liao’s hometown of Siluo (西螺) in Yunlin County to gather data on his relatives.

Even though Liao was president of a provisional republic, Lee writes that in fact, his Formosan Democratic Independence Party (台灣民主獨立黨, FDIP) only consisted of about 30 or so members in addition to the support of a group of Taiwanese immigrants in Japan.

The republic was shaky from the beginning. Just four months after its establishment, the KMT was able to persuade Liao’s relative Chen Che-ming (陳哲民) to return to Taiwan. These defections continued through the next few years, including Chen Chun-you (陳春佑), who returned to Taiwan just a month after he was elected deputy chairman of the FDIP.

Lee writes that Liao was too naiive and was not a strong leader or tactician. By 1959, Lee writes that more than half of FDIP members were actually spying on Liao for the KMT. Other independence groups popped up around that time, and none were willing to work with Liao. His biggest mistakes, Lee writes, were surrendering leadership of the FDIP and telling his members that it was okay to take KMT money as long as they were not “sincerely” working for them. When a follower declared that he was forming his own independence party, Liao not only did not stop him but announced that it was a good thing to have two competing parties working for the same cause.

In 1962, the KMT busted an underground branch of the FDIP in Taiwan, with many of Liao’s relatives being arrested. In 1964, Huang Chi-nan and Liao’s nephew Liao Shih-hao (廖史豪) were sentenced to death with the rest, including Liao Shih-hao’s mother, receiving five to 15 years sentences.

A KMT agent later brought two recordings to give Liao. One was of his mother pleading for him to return home; the other was of his nephew begging his uncle to save him from the death penalty.

The KMT promised Liao that he would not be prosecuted if he returned, and that they would pardon his relatives (which they mentioned by name) and “other comrades.” They also promised him either a government position or chairman of the Taiwan Sugar Company. If Liao wanted to start his own business, the government promised to help him secure bank loans.

With that, Liao came home. The KMT did release Huang and Liao’s relatives, but the “other comrades” remained in jail. Liao remained under government supervision, taking part in the planning of the Zengwen Reservoir and the Port of Taichung. The provisional government carried on without him, but disbanded in January 1977.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

When the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon fell to the North Vietnamese forces 50 years ago this week, it prompted a mass exodus of some 2 million people — hundreds of thousands fleeing perilously on small boats across open water to escape the communist regime. Many ultimately settled in Southern California’s Orange County in an area now known as “Little Saigon,” not far from Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton, where the first refugees were airlifted upon reaching the US. The diaspora now also has significant populations in Virginia, Texas and Washington state, as well as in countries including France and Australia.

On April 17, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) launched a bold campaign to revive and revitalize the KMT base by calling for an impromptu rally at the Taipei prosecutor’s offices to protest recent arrests of KMT recall campaigners over allegations of forgery and fraud involving signatures of dead voters. The protest had no time to apply for permits and was illegal, but that played into the sense of opposition grievance at alleged weaponization of the judiciary by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) to “annihilate” the opposition parties. Blamed for faltering recall campaigns and faced with a KMT chair

A police station in the historic sailors’ quarter of the Belgian port of Antwerp is surrounded by sex workers’ neon-lit red-light windows. The station in the Villa Tinto complex is a symbol of the push to make sex work safer in Belgium, which boasts some of Europe’s most liberal laws — although there are still widespread abuses and exploitation. Since December, Belgium’s sex workers can access legal protections and labor rights, such as paid leave, like any other profession. They welcome the changes. “I’m not a victim, I chose to work here and I like what I’m doing,” said Kiana, 32, as she