Back in 2014, the Chinese-language Apple Daily ran a piece titled “9 weird vegetables in Taiwan that you have never eaten.” As this column makes a return after a prolonged siesta for the Lunar New Year, it is good to rejoice in the fact that some of these vegetables have been covered, as well as many others that are on the fringes of Taiwan’s culinary culture.

Most remain difficult to obtain, though it is good to note that some are gaining a presence in Farmers Association Supermarkets and other establishments that seek to procure and purvey vegetables and other produce that are relatively free of toxic chemical residue. Many of these non-mainstream vegetables are actually better adapted to local conditions, and are good substitutes for better known varieties, providing a cleaner and more often than not, cheaper, alternative.

My own favorite example is the robust sweet potato leaf, covered at the very inception of this column, as the perfect summertime substitute for spinach in a wide variety (though certainly not all) applications. Winter offers a cold weather alternative as well, in the instance of tatsoi, a vegetable remarkable for its ability to survive through chilly winter weather. It looks pretty on the plate and has an outstanding flavor, which I would suggest is in many applications actually superior to the ubiquitous bok choy, of which it is a relative.

Photo: Ian Bartholomew

Tatsoi is a member of the brassica family and is particularly notable for its ability to grow in hard winters, able to withstand temperatures reaching down to -10c, so that it can be harvested even on snow clad ground. This obviously is not a major feature of its appeal in Taiwan, where winter is perfect for many mainstream vegetables to be grown with a minimum of human interference, but its appearance on the scene is still welcome due to its unique and charming personality.

As with many non-mainstream vegetables, tatsoi doesn’t do very well in the marketing department, with its Chinese, in Mandarin takecai (塌棵菜), meaning a vegetable plant that has collapsed. This is a less-than-complimentary reference to the fact that it grows close to the ground, spreading out like a rosette. It has long thin stems and rounded leaves and in English is sometimes referred to as spoon mustard, but with a variety of other names that include spinach mustard, broad beak mustard or rosette bok choy.

With a name that references both spinach and bok choy (青江菜), it is not surprising that it can be substituted for both in a wide variety of applications.

Photo: Ian Bartholomew

Its flavor and textural profile is probably closer to bok choy than to spinach, though its leaves are a little fleshier and its flavor more muted, so that it can be tossed into a green leaf salad in the way you might use baby spinach. It doesn’t need much cooking, and is perfectly delicious slightly wilted with a bit of garlic, or throw it in at the end to finish a simple stir fry.

Unsurprisingly, tatsoi is packed with nutrients, providing a good source of Vitamin C, is rich in calcium and shares many other good qualities with related cruciferous vegetables, possessing all kinds of outstanding anti-oxidant qualities. More surprisingly, it is also a good source of carotenoids, more often associated with orange colored vegetables such as carrots.

Health experts disagree on many things but they mostly agree that rotating your intake of food is generally a good thing. Tatsoi does not bring anything hugely remarkable to the dining table, but for all that it is worth trying out if you come across it. It is pretty to look at, and the fact that it is primarily cultivated on a relatively small scale for sale in farmers markets (to preserve its attractive appearance it needs to be hand harvested) means that it is less likely to be thoroughly impregnated with harmful agricultural chemicals.

Simple Vegetable Rice with Tatsoi

Recipe

(Serves 4)

Vegetable rice is most famously associated with Shanghainese cuisine but its utility as a quick meal has made it such a family favorite that variations abound to such an extent that it is almost impossible to say exactly what is the authentic version. Not having eaten vegetable rice in Shanghai, my only experience of this dish is in Taiwan, and there are a number of establishments that purport to offer the real deal. My own problem with this classic is that I have invariably found it often appears as a damp mass in which neither the rice nor the vegetables are able to shine. Preparing it at home, I am able to adjust for this, cooking a drier firmer rice. Additionally, by using tatsoi, which is equally tasty raw or cooked, I am able to simply wilt the veg in the hot rice, preserving its fresh flavor. As for the meat, tradition dictates the use of Jinhua ham (金華火腿), a specialty of China’s Zhejiang Province, but my own preference is for cured pork belly. When using preserved meats, always ensure to use a high quality product, as some cheaper products are inclined to go over the top with preservatives and stabilizers. Artisanal products from brands such as Gui Lai Biao (桂來標), which operates out of Taipei’s Neihu District (內湖), is one that I personally use, but I am sure there are other excellent brands. Chinese sausage, particularly a type flavored with Chinese rose wine (玫瑰露酒), can be used to produce an even more fragrant version of this dish.

Ingredients

2 cups white rice (short grain)

2 cups chicken stock (vegetable stock or water)

100g cured pork belly

1 clove of garlic

4 stems spring onion

2 dried Chinese mushrooms

200g tatsoi

Directions

1. Place the 100g piece of cured pork belly in a pot of boiling water and cook for 5 minutes.

2. Set aside and allow to cool.

3. Mince the garlic and chop the spring onions.

4. Soak the Chinese mushrooms in boiling water until soft, remove the stem and finely dice the flesh, squeezing out excess liquid.

5. Wash the tatsoi thoroughly and then chop roughly.

6. Finely slice the cooled pork belly.

7. Add a little neutral cooking oil to a pan and gently fry the garlic and pork belly over low heat until fragrant. Add the mushrooms and spring onions and mix, cooking for a further two minutes.

8. Wash the rice thoroughly then add the stock (or water) and the fried ingredients. Mix well and cook until the rice is done. Using a rice cooker is safest, but cooking in a pot works just as well. When the rice is done, add the tatsoi leaves and mix well. There will seem to be vastly too much of the greens but do not worry, they will cook down.

9. Cover and allow residual heat to cook the vegetables, or add a little water and cook for a couple of minutes if you want the vegetables cooked through. Serve warm.

Ian Bartholomew runs Ian’s Table, a small guesthouse in Hualien. He has lived in Taiwan for many years writing about the food scene and has decided that until you look at farming, you know nothing about the food you eat. He can be contacted at Hualien202@gmail.com.

May 18 to May 24 Pastor Yang Hsu’s (楊煦) congregation was shocked upon seeing the land he chose to build his orphanage. It was surrounded by mountains on three sides, and the only way to access it was to cross a river by foot. The soil was poor due to runoff, and large rocks strewn across the plot prevented much from growing. In addition, there was no running water or electricity. But it was all Yang could afford. He and his Indigenous Atayal wife Lin Feng-ying (林鳳英) had already been caring for 24 orphans in their home, and they were in

President William Lai (賴清德) yesterday delivered an address marking the first anniversary of his presidency. In the speech, Lai affirmed Taiwan’s global role in technology, trade and security. He announced economic and national security initiatives, and emphasized democratic values and cross-party cooperation. The following is the full text of his speech: Yesterday, outside of Beida Elementary School in New Taipei City’s Sanxia District (三峽), there was a major traffic accident that, sadly, claimed several lives and resulted in multiple injuries. The Executive Yuan immediately formed a task force, and last night I personally visited the victims in hospital. Central government agencies and the

Australia’s ABC last week published a piece on the recall campaign. The article emphasized the divisions in Taiwanese society and blamed the recall for worsening them. It quotes a supporter of the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) as saying “I’m 43 years old, born and raised here, and I’ve never seen the country this divided in my entire life.” Apparently, as an adult, she slept through the post-election violence in 2000 and 2004 by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), the veiled coup threats by the military when Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) became president, the 2006 Red Shirt protests against him ginned up by

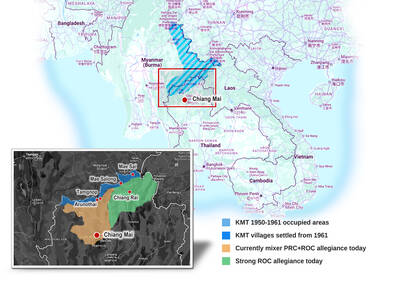

As with most of northern Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) settlements, the village of Arunothai was only given a Thai name once the Thai government began in the 1970s to assert control over the border region and initiate a decades-long process of political integration. The village’s original name, bestowed by its Yunnanese founders when they first settled the valley in the late 1960s, was a Chinese name, Dagudi (大谷地), which literally translates as “a place for threshing rice.” At that time, these village founders did not know how permanent their settlement would be. Most of Arunothai’s first generation were soldiers