The story behind this book makes for good news for Taiwan, though when I started reading it the reverse seemed to be the case. Let me explain.

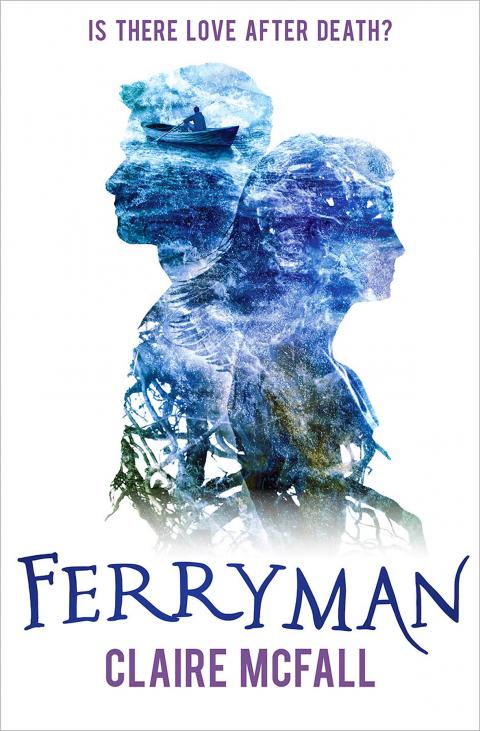

The Ferryman is a novel for young adults written by a school teacher from Peebles in southern Scotland. It has had a certain amount of success in her native Scotland, though less so south of the border in England. But where it has really taken off is in China, where it has assumed the stature of another Harry Potter book. Over a million copies have been sold there, and its sequel, Trespassers, has proved equally popular. Both books have been in the Chinese best-selling fiction charts for many months. The author has already visited the country on a book-signing tour and was astonished by the enthusiasm she encountered.

The translation, of course, is in China’s simplified script, and all seems set for an even bigger success when the books, plus a third still being written, are filmed by Legendary Entertainment, responsible for such successes as Godzilla and Pacific Rim, in both English and Chinese versions.

Meanwhile, what about Taiwan, with its traditional Chinese script? As I say, originally I thought it was missing out on a phenomenon that could equal Harry Potter’s extraordinary success. But the news has just arrived that Taipei’s Yuan-Liou Publishing (遠流出版公司) has now secured the rights, and a version of The Ferryman in unreformed characters will be appearing in Taiwan in the second half of this year.

So, what kind of a book is it? It’s the story of a 15-year-old Scottish girl, Dylan, who lives, not very happily, with her peevish and interfering mother. One day she sets off by train to meet her father for the first time, but in the middle of a tunnel something happens. Everything goes black, and Dylan crawls out into the daylight to find no evidence of any of the other passengers. All she can see is a boy sitting on a grassy bank looking at her.

This boy, she discovers, is called Tristan, and he quickly informs her that she has died, and that he is her ferryman, appointed to lead her across a wasteland to the border of the afterlife. And so it is that they set off, beleaguered by hostile wraiths who attempt to snatch at Dylan and drag her down into a distinctly uncongenial nether-world. They find safety, however, at night (the only time the wraiths are able to emerge) in a series of safe houses, and finally arrive at their destination.

In the meantime, however, Dylan and Tristan have fallen in love. Tristan has ferried thousands of souls along this same route and insists he cannot cross over with Dylan to where she is going. Eventually, though, he says that at least he’ll try.

It’s about half way through the book that Dylan crosses over to the land beyond the veil. But to her horror, Tristan isn’t there with her. She eventually seeks out one of Tristan’s former charges, a young man who was a Nazi officer during World War II, who Tristan says was the most saintly person he’d ever met. He’d met his death when he refused to shoot the inmate of a concentration camp he’d been assigned to. This is a fine example of the unpredictability of Claire McFall’s imagination.

Idyllic though this otherworld seems, Dylan wants nothing more than to be reunited with Tristan. The former German officer advises her that any return is universally regarded as impossible, though he hints there are ways she might try to achieve it.

Suffice it to say that a reunification between Dylan and Tristan does eventually take place, after which the question arises as to whether a return to the life before death, the life that appeared to end for Dylan on the ill-fated train, is possible, and if it is, can Tristan accompany her there?

There may be a bit too much on the difficulties of crossing various kinds of hostile terrains in this book, but this is a Scottish novel after all, and much of Scotland is as wild and rugged as the other-worldly landscapes described. It is, nevertheless, a gripping read, and tearful adolescents waiting outside Chinese bookshops to buy a copy, and maybe even meet the author, are entirely understandable.

There are similarities to the Harry Potter books, in that someone from an unhappy home travels to a mysterious world in which all kinds of magic proves possible. But there’s nothing like the same range of characters as you meet at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry. The Ferryman, though, is only the first volume of a trilogy, so who knows what people the author will later come up with.

Writing for young adults — readers around the same age as Dylan and Tristan in other words — is a special kind of art. Physical attraction is all right, and indeed strongly described, but actual sex, so far at least, is probably unacceptable. But of course I may be proved entirely wrong in this by the subsequent volumes.

Taiwanese readers wanting to read this book in Chinese will have to wait another six months or so, but the book is readily available in English, as is Trespassers (published in the UK last year), scheduled to eventually be the middle volume of the trilogy. The third installment is due next year.

I’m a good deal older than anything that could be described as “young adult,” but I nonetheless found The Ferryman an enjoyable and compelling read. I conclude, therefore, that, as with the Harry Potter books, people of all ages will enjoy the mysterious world the author has created for us. Maybe it takes a teacher (though Claire McFall has now given up her “day job”) to understand just how adolescents really think.

Following the shock complete failure of all the recall votes against Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers on July 26, pan-blue supporters and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) were giddy with victory. A notable exception was KMT Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫), who knew better. At a press conference on July 29, he bowed deeply in gratitude to the voters and said the recalls were “not about which party won or lost, but were a great victory for the Taiwanese voters.” The entire recall process was a disaster for both the KMT and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). The only bright spot for

As last month dawned, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was in a good position. The recall campaigns had strong momentum, polling showed many Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers at risk of recall and even the KMT was bracing for losing seats while facing a tsunami of voter fraud investigations. Polling pointed to some of the recalls being a lock for victory. Though in most districts the majority was against recalling their lawmaker, among voters “definitely” planning to vote, there were double-digit margins in favor of recall in at least five districts, with three districts near or above 20 percent in

From Godzilla’s fiery atomic breath to post-apocalyptic anime and harrowing depictions of radiation sickness, the influence of the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki runs deep in Japanese popular culture. In the 80 years since the World War II attacks, stories of destruction and mutation have been fused with fears around natural disasters and, more recently, the Fukushima crisis. Classic manga and anime series Astro Boy is called “Mighty Atom” in Japanese, while city-leveling explosions loom large in other titles such as Akira, Neon Genesis Evangelion and Attack on Titan. “Living through tremendous pain” and overcoming trauma is a recurrent theme in Japan’s

The great number of islands that make up the Penghu archipelago make it a fascinating place to come back and explore again and again. On your next trip to Penghu, why not get off the beaten path and explore a lesser-traveled outlying island? Jibei Island (吉貝嶼) in Baisha Township (白沙鄉) is a popular destination for its long white sand beach and water activities. However, three other permanently inhabited islands in the township put a unique spin on the traditional Penghu charm, making them great destinations for the curious tourist: Yuanbeiyu (員貝嶼), Niaoyu (鳥嶼) and Dacangyu (大倉嶼). YUANBEIYU Citou Wharf (岐頭碼頭) connects the mainland