JAN. 8 to Jan. 14

When former president Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國) died on Jan. 13, 1988, the reactions were quite different from when his father, Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) passed away 13 years earlier.

With the elder Chiang, “the press and ranking officials had employed the contrived language of the imperial court to describe the ‘greatness’ of the departed ruler,” writes Jay Taylor in The Generalissimo’s Son. “But following Ching-kuo’s death ... the traditionally extravagant and quasi-religious titles and praise were absent. Instead, media commentary and individual eulogies focused on Chiang Ching-kuo’s empathy for the common person.”

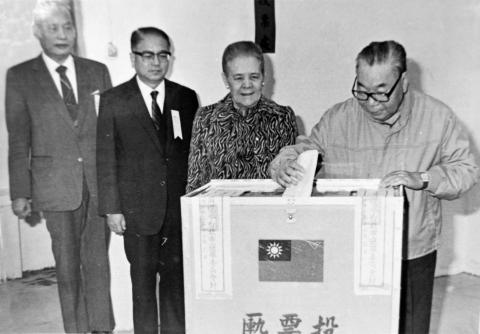

Photo: Chen Tse-ming, Taipei Times

Also different was who would take over — with Chiang Kai-shek, it was a given that his son would eventually succeed his presidency. But in an 1985 interview with Time magazine, Chiang made it clear that no member of his family would be a candidate for the next president, and that everything would be done under constitutional procedures. Later that year, he reportedly veered off script to make the same statement during a National Assembly meeting.

Vice-president Lee Teng-hui (李登輝) took over after Chiang’s death, though it took a bit of political maneuvering for Lee to solidify his power. And with that, 39 years of Chiang rule in Taiwan was over.

NOT-SO-IRON GRIP

Photo: Hsu Hui-ling, Taipei Times

Chiang Kai-shek and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) ruled Taiwan under martial law with an iron fist for three decades, but by the time Chiang Ching-kuo took over in 1978, he faced a vastly different political landscape.

“The political opposition became more articulate in its demands, while the regime faced a loss of credibility among the politically active population as a result of the growing discrepancy between its self-characterization as a democracy and maintenance of a martial law regime,” writes Hermann Halbeisen in In Search of a Political Order? Political Reform in Taiwan.

A number of significant events took place in the 1970s and 1980s that led to the situation. Internationally, Taiwan was out of the UN while the US cut ties with Taiwan in favor of China. The Jhongli Incident of 1977, where rioters burnt down a police station in response to alleged ballot tampering by the KMT, is said to be the first large-scale civil disturbance in nearly 30 years. There was the Kaohsiung Incident in 1979 that led to a mass arrest of opposition leaders, and in 1984 the government allegedly hired gangsters to assassinate US-based journalist Henry Liu (劉宜良), who published an unflattering biography on Chiang Ching-kuo. With each incident, the KMT’s credibility and image dropped further.

Photo: Chen Hsin-jen, Taipei Times

Calls for reform even came from within. In the study The Transition to the Transition Toward Democracy in Taiwan, Phillip Newell writes, “The KMT would not have chosen reform, however, except that under pressure from intellectuals, the democratic opposition and critics in the US, ‘softliners’ in the KMT gradually convinced the pragmatic leader that the hardliner policy or resisting change indefinitely would undermine the KMT’s ability to win domestic and international supporters. The KMT thus chose to accept political pluralism and competition.”

“If we don’t rejuvenate the KMT, people will give up on the party, even its members will drift away,” Chiang is quoted to have said.

TAIWANESE SUCCESSOR

Chiang Ching-kuo’s “localization” policies began during his tenure as premier. For example, he appointed Taiwan-born Hsu Ching-chung (徐慶鐘) as his deputy and his cabinet included three Taiwan-born ministers without portfolio — including Lee Teng-hui.

Chen Shih-horng (陳世宏) writes in Lee Teng-hui and the Democratization of Taiwan that this was merely a “strategy of pacification.” Most Taiwanese were still barred from real positions of power and the population was still under the restrictions of martial law. But it paved the way for people like Lee, who became Taipei’s mayor in 1978.

Former CIA station chief in Taiwan Ray S. Cline writes in Chiang Ching-kuo Remembered that Chiang held Lee in high regard. Chiang told Cline that Lee not only had great expertise in economics, but he hoped that Lee could cooperate with the China-born leaders and “take great responsibility within the system of multicultural, technologically advanced government developing in the Republic of China.”

Cline first met Lee during his tenure as mayor, leaving with a favorable impression.

“It was apparent to me, although Chiang Ching-kuo never said it specifically in those words, that … he was grooming Lee Teng-hui as a potential successor. I believe that it was his assumption in the later years of his life that another quasi-dynastic succession would be damaging.”

Lee has said that he graduated from the “Chiang Ching-kuo Academy,” which Chen writes did not mean Chiang’s rule as strongman but rather his pragmatism in assessing the situation and willingness to look at alternative solutions. In 1984, Chiang named him vice-president.

“I still respect Chiang Ching-kuo very much,” Lee writes in his memoir, The Remaining Years: My Life Journey and the Road of Taiwan’s Democracy (餘生: 我的生命之旅與台灣民主之路). “He was willing to consider what use he would have for someone born in Taiwan with the personality of a Japanese. That gave me a chance to be the first Taiwan-born president in history. I believe that he had thought it through and realized that the KMT was not going to last long with dictatorship.”

Despite the effort of certain KMT members to block the move, Lee was named acting KMT chairman on Jan. 27, 1988.

“For all practical purposes, by January 1988, democracy, imperfect and rowdy as it was, had made a soft touchdown in Taiwan,” Taylor writes.

Lee, for his part, gives the credit to Chiang, noting that nobody besides Chiang would have dared to terminate martial law.

“Let’s not talk about what Chiang did in the past,” he writes. “He is the one who initiated Taiwan’s democratization process. If it weren’t for his decisions, I would never have been able to launch my plans for democratization. Think about it. Why would the National Assembly and Legislature listen to me?”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Behind a car repair business on a nondescript Thai street are the cherished pets of a rising TikTok animal influencer: two lions and a 200-kilogram lion-tiger hybrid called “Big George.” Lion ownership is legal in Thailand, and Tharnuwarht Plengkemratch is an enthusiastic advocate, posting updates on his feline companions to nearly three million followers. “They’re playful and affectionate, just like dogs or cats,” he said from inside their cage complex at his home in the northern city of Chiang Mai. Thailand’s captive lion population has exploded in recent years, with nearly 500 registered in zoos, breeding farms, petting cafes and homes. Experts warn the

The unexpected collapse of the recall campaigns is being viewed through many lenses, most of them skewed and self-absorbed. The international media unsurprisingly focuses on what they perceive as the message that Taiwanese voters were sending in the failure of the mass recall, especially to China, the US and to friendly Western nations. This made some sense prior to early last month. One of the main arguments used by recall campaigners for recalling Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers was that they were too pro-China, and by extension not to be trusted with defending the nation. Also by extension, that argument could be

Aug. 4 to Aug. 10 When Coca-Cola finally pushed its way into Taiwan’s market in 1968, it allegedly vowed to wipe out its major domestic rival Hey Song within five years. But Hey Song, which began as a manual operation in a family cow shed in 1925, had proven its resilience, surviving numerous setbacks — including the loss of autonomy and nearly all its assets due to the Japanese colonial government’s wartime economic policy. By the 1960s, Hey Song had risen to the top of Taiwan’s beverage industry. This success was driven not only by president Chang Wen-chi’s

Last week, on the heels of the recall election that turned out so badly for Taiwan, came the news that US President Donald Trump had blocked the transit of President William Lai (賴清德) through the US on his way to Latin America. A few days later the international media reported that in June a scheduled visit by Minister of National Defense Wellington Koo (顧立雄) for high level meetings was canceled by the US after China’s President Xi Jinping (習近平) asked Trump to curb US engagement with Taiwan during a June phone call. The cancellation of Lai’s transit was a gaudy