Abubakar Ya’u digs sand from vast, sweeping dunes and loads heavy hessian sacks of the fine, golden bounty onto the backs of donkeys which carry it to market.

Rampant demand for the beasts of burden in China, where their skins are believed to have medicinal properties, has caused prices to soar — creating a dilemma for Ya’u and his fellow excavators in Kano, northern Nigeria.

“Two years ago we were buying donkeys strong enough for our trade for between 15,000 and 18,000 naira (between US$42 and US$50) — but now to get a good donkey you will require 70,000 to 75,000,” he said, wearing dusty sandals, jeans and a T-shirt.

Photo courtesy of Pixabay

“The reason for this is the huge purchase of donkeys which are transported to the south where their meat is consumed and their skin exported,” he explained.

“To us, it is a calamity because as a sand digger if you lose your donkey, you can hardly raise the money to replace it.”

Fellow sand digger Abdurrahman Garba, who has been in the business for 30 years, added that export bans by some of Nigeria’s neighbours had made the situation worse.

“Now that Niger has banned donkey exports to save its stock, the Chinese have turned to our stock — depleting them at an alarming rate,” said Garba, 40.

Botswana, Senegal, Mali, Burkina Faso and Gambia all impose restrictions on the trade, while Zimbabwean authorities blocked a private donkey slaughterhouse under construction and Ethiopia closed its only functioning abattoir.

CHINESE ‘MEDICINE’

Garba admitted that the temptation to sell the animals for short-term gain could be overwhelming.

“I was offered 95,000 naira for my biggest donkey but I fought hard to resist the temptation to sell it because I knew I will not be able to replace it,” he said. “We blame the Chinese for this disturbing situation.”

The animals are increasingly being transported, sometimes covertly, from Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso and northern Nigeria to the southeast where they are then typically slaughtered.

Donkeys are relatively cheaper in the Muslim-majority north as they are typically not slaughtered for their meat, tempering demand. But the north-south trade route for donkeys was already well established as consumption has traditionally been relatively high in the south where some communities have long eaten the animals. At a market in Ughelli, Delta State — the center of the Nigerian donkey trade — hundreds of donkeys are crammed into pens under the burning sun as they await their fate. Some are skeletally thin, all are quiet.

New animal pens are being made every month as the demand for donkey hides and meat is met with an steadily growing supply from the north.

From Delta state on Nigeria’s southern coast, hides are shipped to China where they are stewed to render the coveted gelatin known as ejiao (阿膠) in Chinese.

The buyers, who believe that soluble ejiao gum is an effective remedy for troubles ranging from colds to aging, comprise a market thought to be worth hundreds of millions of dollars every year.

“The medicine is popularly referred to as a blood tonic and helps to fortify the body, particularly in conditions like anaemia,” said Oliver Emekpor, a butcher handling donkey meat at the Ughelli market.

“It comes in blocks of dried pieces which are melted down into a brew of herbal mixture to drink and sells for up to US$390 per kilo.”

Nothing is wasted. To maximize profits, donkey dealers often sell the remaining meat to unwary consumers as beef, a practice described by a local trade association as “criminal”.

Hooves are used to make shoes and donkey bones are used to manufacture plates.

DROPPING POPULATION

Simon Pope, a campaigner at the Donkey Sanctuary, a British animal welfare charity, said that the scale of the donkey trade is almost impossible to estimate.

“Each donkey hide produces one kilogram of Ejiao and there is a huge uncertainty about how many hides are being used annually,” he said.

Yemi Adebayo, an official at Nigeria’s trade ministry, acknowledged that donkey hide sales to China are booming, but refused to confirm if any deal had been struck to facilitate shipments.

“Different countries either support or oppose the trade in different ways,” he said, but the status of the activity in Nigeria remained unclear.

Dong-E E-Jiao is China’s market leader for the manufacture and sale of ejiao, controlling 70 percent of the market. The firm posted pre-tax profits of US$295 million last year and handled roughly 700,000 donkey hides in 2014 alone.

Donkey numbers in China have nearly halved from 11 million in the 1990s to six million in 2013, according to official statistics.

China produces 5,000 tons of ejiao each year, requiring some four million hides, according to the China Daily.

“The strong players will get stronger amid the scarcity of donkeys and decreasing supply of donkey hide,” wrote BOCOM International financial services in a research note for investors.

The Donkey Sanctuary’s investigation into the trade, Under the Skin, revealed that the explosion in demand had led to a surge in donkey thefts in Africa, Asia and South America.

“Donkeys may soon go extinct if they continue to be killed,” said Garba, the veteran sand digger. “Once they are finished, our trade will suffer.”

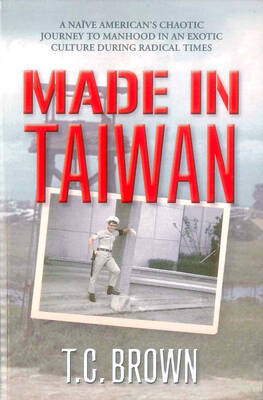

By 1971, heroin and opium use among US troops fighting in Vietnam had reached epidemic proportions, with 42 percent of American servicemen saying they’d tried opioids at least once and around 20 percent claiming some level of addiction, according to the US Department of Defense. Though heroin use by US troops has been little discussed in the context of Taiwan, these and other drugs — produced in part by rogue Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) armies then in Thailand and Myanmar — also spread to US military bases on the island, where soldiers were often stoned or high. American military policeman

Under pressure, President William Lai (賴清德) has enacted his first cabinet reshuffle. Whether it will be enough to staunch the bleeding remains to be seen. Cabinet members in the Executive Yuan almost always end up as sacrificial lambs, especially those appointed early in a president’s term. When presidents are under pressure, the cabinet is reshuffled. This is not unique to any party or president; this is the custom. This is the case in many democracies, especially parliamentary ones. In Taiwan, constitutionally the president presides over the heads of the five branches of government, each of which is confusingly translated as “president”

An attempt to promote friendship between Japan and countries in Africa has transformed into a xenophobic row about migration after inaccurate media reports suggested the scheme would lead to a “flood of immigrants.” The controversy erupted after the Japan International Cooperation Agency, or JICA, said this month it had designated four Japanese cities as “Africa hometowns” for partner countries in Africa: Mozambique, Nigeria, Ghana and Tanzania. The program, announced at the end of an international conference on African development in Yokohama, will involve personnel exchanges and events to foster closer ties between the four regional Japanese cities — Imabari, Kisarazu, Sanjo and

Sept. 1 to Sept. 7 In 1899, Kozaburo Hirai became the first documented Japanese to wed a Taiwanese under colonial rule. The soldier was partly motivated by the government’s policy of assimilating the Taiwanese population through intermarriage. While his friends and family disapproved and even mocked him, the marriage endured. By 1930, when his story appeared in Tales of Virtuous Deeds in Taiwan, Hirai had settled in his wife’s rural Changhua hometown, farming the land and integrating into local society. Similarly, Aiko Fujii, who married into the prominent Wufeng Lin Family (霧峰林家) in 1927, quickly learned Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) and