Niaz Ali is a deeply religious man: He prays five times a day and visits the mosque as frequently as possible. But he also loves to smoke hashish — lots of it.

Despite it being forbidden by his faith, the 50 year-old estimates he spends about 30 percent of his earnings as a cab driver on the habit. His love affair with cannabis began as an occasional puff with friends when he was a teenager, but has since morphed into a full-blown addiction for the father-of-nine.

“It is a sacred plant. A sacred intoxication,” says Ali, who asked to use a pseudonym, after taking a fresh rip off a hookah packed with pungent hash in Pakistan’s bustling northwestern town of Peshawar. “It’s like a second wife, this addiction,” he sighs. While Ali freely acknowledges using hash runs counter to the tenets of Islam, he insists it has its advantages.

Photo: AFP

“We know that it is haram (forbidden by Islamic law) but it’s an intoxication that doesn’t harm anyone else,” he explains. In conservative Pakistan, an Islamic republic, the consumption of alcohol is strictly forbidden for Muslims. Any semblance of a sybaritic nightlife takes place at home behind closed doors, where the country’s elite have been known to quaff booze.

But many Pakistanis are surprisingly open to using cannabis, with the spongy, black hash made from marijuana grown in the country’s tribal belt and neighboring Afghanistan the preferred variant of the drug.

Whereas alcohol is explicitly forbidden in Islamic scripture, hash seemingly straddles a theological gray zone, which could explain its popularity in the country.

Even if most observant Muslims in Pakistan scoff at the idea of drinking, a prod into their feelings on marijuana often triggers a wry smile followed by a trite maxim about how good it makes food taste or how restful sleep can be after a toke.

NO COMPROMISE

People have been smoking hash on the subcontinent for centuries.

It predates the arrival of Islam in the region, with reference to cannabis appearing in the sacred Hindu Atharva Veda text describing its medicinal and ritual uses.

According to a 2013 UN survey, cannabis was the most widely consumed drug in Pakistan with around four million users, representing 3.6 percent of the population — a figure that has drawn skepticism in a country where reliable data can be hard to come by.

“It’s an underestimation,” says Dr. Parveen Azam Khan, president of the Dost Welfare Foundation, a nonprofit that treats drug addicts in Peshawar.

Despite its widespread consumption, not all are happy about hash’s prevalence in the so-called “Land of the Pure.”

“There is no compromise with hashish,” says Maulana Mohammad Tayyab Qureshi, the imam of the main Peshawar mosque.

According to Qureshi, anything that causes intoxication or bodily harm is strictly forbidden in the faith. He chalks up marijuana’s popularity in Pakistan as a law enforcement issue.

Public health experts also warn the ubiquitous availability of cheap hash in Pakistan’s northwest has been especially harmful to impoverished children, who increasingly use the drug to deal with the hardships of poverty and trauma from years of militant violence.

“For children, it’s the drug of choice,” says Dr. Khan, blaming the vicious nexus between the region’s narco-funded insurgencies and widespread drug use for the scourge.

Pakistan also remains wholly unequipped to handle the problem, with the UN survey saying a dearth of treatment clinics and prohibitive costs keeps users from seeking help.

TOLERATED IN SHRINES

But in Islamic shrines salted across the country others see cannabis as more benign.

At the Bari Badshah shrine in the heart of Peshawar, followers of the Sufi sect of Islam gather in a small courtyard nightly, where they smoke copious amounts of hash and listen to devotional music while draining tea by the kettle.

Conversations are fluid, only to be interrupted by hard drags off hash pipes with the occasional song performed by one of the devotees.

“The basic work of hash... it wakes up new corners in your mind,” says Mohammed Amin, 50.

According to Sayeed Asjid, 27, such shrines are welcome to members of any faith and in Peshawar are frequented by high-level bureaucrats, police officers and members of security agencies.

“It’s a deep relaxation,” says Asjid of the cannabis high as he exhales clouds of marijuana smoke.

But Sufi shrines have been the frequent target over the years by Taliban militants and sectarian extremists like the Islamic State group, who view the mystical sect as heretical.

“That was only to spread fear and havoc,” says Asjid of the attacks, while expressing his faith in the power of the shrine to protect.

The herb is not only enjoyed by free-spirited Sufi mystics.

Mehwish, a single mother of three, says the occasional joint helps manage the stress that comes with the daily grind.

“You can use hash when you are alone... then you can think in a relaxed way,” says Mehwish, whose name has been changed on request.

Although she admits most of her family are unaware of her habit, the 26-year-old is a firm believer in its benefits.

She adds: “When you feel good and you’re active and it puts a smile on your face then nobody minds.”

May 26 to June 1 When the Qing Dynasty first took control over many parts of Taiwan in 1684, it roughly continued the Kingdom of Tungning’s administrative borders (see below), setting up one prefecture and three counties. The actual area of control covered today’s Chiayi, Tainan and Kaohsiung. The administrative center was in Taiwan Prefecture, in today’s Tainan. But as Han settlement expanded and due to rebellions and other international incidents, the administrative units became more complex. By the time Taiwan became a province of the Qing in 1887, there were three prefectures, eleven counties, three subprefectures and one directly-administered prefecture, with

President William Lai (賴清德) yesterday delivered an address marking the first anniversary of his presidency. In the speech, Lai affirmed Taiwan’s global role in technology, trade and security. He announced economic and national security initiatives, and emphasized democratic values and cross-party cooperation. The following is the full text of his speech: Yesterday, outside of Beida Elementary School in New Taipei City’s Sanxia District (三峽), there was a major traffic accident that, sadly, claimed several lives and resulted in multiple injuries. The Executive Yuan immediately formed a task force, and last night I personally visited the victims in hospital. Central government agencies and the

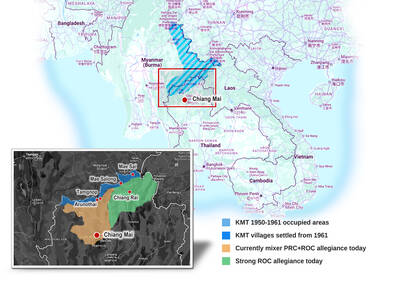

Among Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) villages, a certain rivalry exists between Arunothai, the largest of these villages, and Mae Salong, which is currently the most prosperous. Historically, the rivalry stems from a split in KMT military factions in the early 1960s, which divided command and opium territories after Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) cut off open support in 1961 due to international pressure (see part two, “The KMT opium lords of the Golden Triangle,” on May 20). But today this rivalry manifests as a different kind of split, with Arunothai leading a pro-China faction and Mae Salong staunchly aligned to Taiwan.

As with most of northern Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) settlements, the village of Arunothai was only given a Thai name once the Thai government began in the 1970s to assert control over the border region and initiate a decades-long process of political integration. The village’s original name, bestowed by its Yunnanese founders when they first settled the valley in the late 1960s, was a Chinese name, Dagudi (大谷地), which literally translates as “a place for threshing rice.” At that time, these village founders did not know how permanent their settlement would be. Most of Arunothai’s first generation were soldiers