It’s rather ironic that, despite its rich heritage of lovely old historic remains, Changhua’s most famous sight is a huge statue of the sitting Buddha, built in 1962. There’s a lot more to Changhua (彰化), however, than this huge, gleaming black Shakyamuni Buddha figure that announces the approaching city long before arrival.

For a place that tends to fall beneath the radar, perhaps because the more famous historic town of Lukang (鹿港) is only 30 minutes away, it’s a very rewarding city to walk around, with an unexpectedly rich heritage of fine old architecture, and plenty of history.

The city boasts one of Taiwan’s finest Confucius Temples (孔廟), but the streets are dotted with other lovely and much less famous old shrines, most with graceful, swallow-tailed roofs and fronted by peaceful courtyards. Complementing the religious architecture are some interesting relics from the Japanese colonial era, and some great traditional food.

Photo: Richard Saunders

OFF THE RAILS

Just off Heping Road (和平路), a five-minute walk from the railway station, is the fan-shaped Railway Depot (扇形車庫), built in 1922 and still in use. The only one of its kind in Taiwan and, according to some reports, maybe the only operational one left in Asia, it’s a compulsory stop for local and foreign train enthusiasts alike, featuring a large circular turntable where engines can be turned. Register with the guard at the entrance before going in for a look.

Most of Changhua’s historic buildings lie in a small cluster in the center of town, an easy 10 minute stroll from the railway station. Walk down Jhonghua Road (中華路) and turn right beside Fude Temple (福德祠), which is unusual both for its size and for the high quality of its workmanship, and go down a narrow alley to the lovely Shengwang Temple (聖王宮), set back from the road (like most of Changhua’s old temples) behind an attractive stone courtyard. Just around the corner at 467 Minzu Road (民族路) is Guandi Temple (關帝廟), which has a pair of gnarled old trees in the large front courtyard.

Photo: Richard Saunders

Past Guandi Temple, turn right into Yongle Street (永樂街), and on the left in one block is little Cingan Temple (慶安宮), established exactly two centuries ago. A couple of minutes’ walk north, serene little Kaihua Temple (開化寺) is sheltered from the traffic on busy Jhonghua Road by a smart white wall and gate. A block away, standing across from each other at the intersection of Changan Street (長安街) and Chenleng Road (陳稜路), are a pair of eateries serving Changhua’s best rouyuan (肉圓) — a delicious traditional Taiwanese meatball made with pork and bamboo.

As you may have noticed by now, Changhua is one of Taiwan’s oldest towns: it was already a bustling place 300 years ago. It even boasts a rare reminder of the brief Dutch colonial presence in Taiwan. Near the city’s famous Confucius Temple, behind the big, modern red-brick city library building on busy Jhongshan Road (中山路), a metal canopy shelters the Hongmao Well (紅毛井). It’s not much to look at, but it was dug by Dutch settlers nearly four centuries ago. In front of it is the fine, Japanese-era Zhongshan Hall (中山堂) with art deco features.

BATTLE GROUND

Photo: Richard Saunders

Walk through the large ornamental gate beside the city library into Gongyuan Road (公園路) and on the left immediately behind the library building are the curved brick walls of the 1895 Baguashan Anti-Japanese Martyrs’ Museum (1895八卦山抗日保台史蹟館). Changhua was one of the last parts of Taiwan to hold out against the Japanese invading forces in 1895, and one of the biggest battles that year took place in August on the strategically important mountain, Baguashan (八卦山), just above the city, where over 1,000 Taiwanese were killed.

The museum, closed Mondays, provides a Chinese introduction to the events, with lots of photos and audio-visuals. It’s laid out partly in the network of air-raid shelters and tunnels that riddle the hillside.

In 1965 a total of 679 human skeletons were unearthed on the slopes of nearby Baguashan, close to where the Big Buddha stands today. They are the remains of locals who died here during the fierce battle against the invading Japanese army. The 1895 Anti-Japanese Martyrs’ Memorial Park (抗日烈士紀念公園, also called Peace Memorial Park) was built on the site to commemorate the dead. A large ceremonial gate marks the entrance, on Guashan Road (八卦路), a few hundred meters east of the Big Buddha, while inside are two Qing Dynasty cannons — all that remains of a fort that once stood here.

Photo: Richard Saunders

A few meters further along Gongyuan Road past the library is another of the city’s impressive Japanese-era structures, the Butokuden (武德殿). Built in 1930, it was one of a series of buildings built to teach martial arts to Japanese police officers. Next to it is a much older edifice, the Jiesiao Shrine (節孝祠), yet another of Changhua’s many old temples, but one with a difference — said to be the only one in Taiwan dedicated to chaste ladies.

Richard Saunders is a classical pianist and writer who has lived in Taiwan since 1993. He’s the founder of a local hiking group, Taipei Hikers, and is the author of six books about Taiwan, including Taiwan 101 and Taipei Escapes. Visit his Web site at www.taiwanoffthebeatentrack.com.

Following the shock complete failure of all the recall votes against Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers on July 26, pan-blue supporters and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) were giddy with victory. A notable exception was KMT Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫), who knew better. At a press conference on July 29, he bowed deeply in gratitude to the voters and said the recalls were “not about which party won or lost, but were a great victory for the Taiwanese voters.” The entire recall process was a disaster for both the KMT and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). The only bright spot for

Water management is one of the most powerful forces shaping modern Taiwan’s landscapes and politics. Many of Taiwan’s township and county boundaries are defined by watersheds. The current course of the mighty Jhuoshuei River (濁水溪) was largely established by Japanese embankment building during the 1918-1923 period. Taoyuan is dotted with ponds constructed by settlers from China during the Qing period. Countless local civic actions have been driven by opposition to water projects. Last week something like 2,600mm of rain fell on southern Taiwan in seven days, peaking at over 2,800mm in Duona (多納) in Kaohsiung’s Maolin District (茂林), according to

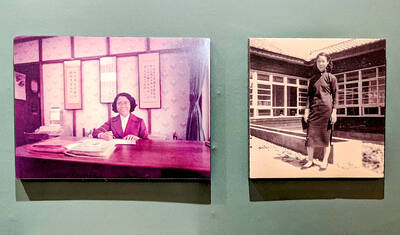

Aug. 11 to Aug. 17 Those who never heard of architect Hsiu Tse-lan (修澤蘭) must have seen her work — on the reverse of the NT$100 bill is the Yangmingshan Zhongshan Hall (陽明山中山樓). Then-president Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) reportedly hand-picked her for the job and gave her just 13 months to complete it in time for the centennial of Republic of China founder Sun Yat-sen’s birth on Nov. 12, 1966. Another landmark project is Garden City (花園新城) in New Taipei City’s Sindian District (新店) — Taiwan’s first mountainside planned community, which Hsiu initiated in 1968. She was involved in every stage, from selecting

As last month dawned, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was in a good position. The recall campaigns had strong momentum, polling showed many Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers at risk of recall and even the KMT was bracing for losing seats while facing a tsunami of voter fraud investigations. Polling pointed to some of the recalls being a lock for victory. Though in most districts the majority was against recalling their lawmaker, among voters “definitely” planning to vote, there were double-digit margins in favor of recall in at least five districts, with three districts near or above 20 percent in