Nov. 27 to Dec. 3

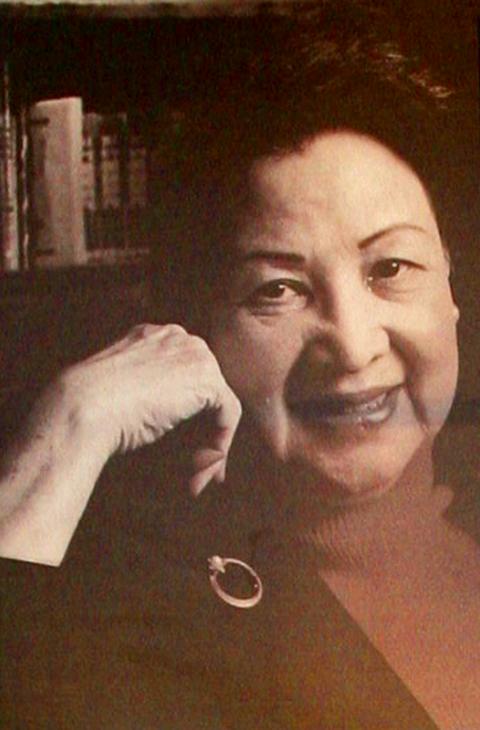

Lin Hai-yin (林海音) was a talented writer who also had an eye for talent.

As editor of the United Daily News literary supplement (聯合報副刊), Lin published the first pieces of future literary heavyweights such as Chi Teng Sheng (七等生), Cheng Ching-wen (鄭清文) and Huang Chun-ming (黃春明).

Photo: Hu Shun-hsiang, Taipei Times

Lin also encouraged writers such as Chung Chao-cheng (鍾肇政) and Chung Li-ho (鍾理和), who were educated during the Japanese colonial era, to continue writing — even though they were forced to work in Mandarin because the newly-arrived Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) had banned the use of their native Japanese in 1946. Lin recognized the value of their work, and took the time to edit their clunky Mandarin so they could be published.

Among these pieces was Chung Chao-cheng’s Lupine Flower (魯冰花), one of the first full-length novels by a Taiwanese writer to be serialized in newspapers after World War II. The novel, which critics generally agree is a classic of Taiwanese literature, received the movie treatment in 1989 and 2009.

Cheng says in Lin’s biography that “Taiwan’s literary scene would have arrived five or 10 years later if not for Lin Hai-yin.”

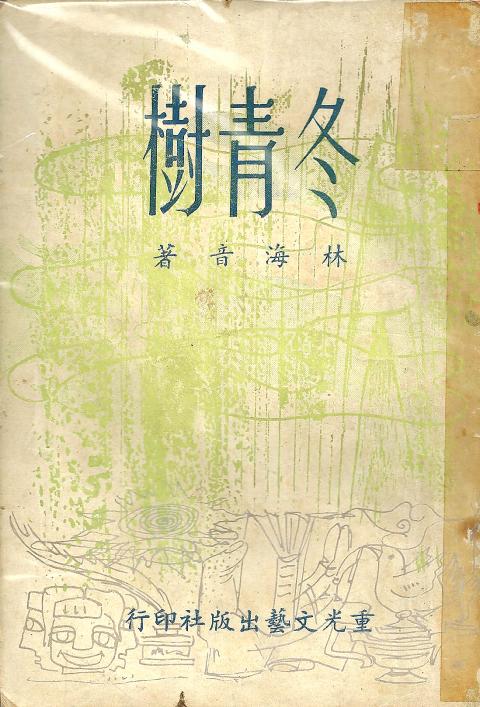

Photo courtesy of Ying Feng-huang

UNEARTHING LOCAL TALENT

There was not much of a stage for literature written by Taiwanese authors during the early days of KMT rule because the party prioritized Mandarin over all other languages and held an iron grip over published materials.

“We did not have the life experiences to break into the 1950s scene, which championed anti-communist and war literature,” Chung says, noting that it was a big deal when Chiayi-born writer Wen Hsin’s (文心) novel, Thousand Year Cypress (千年檜), appeared in the literary supplement in 1957.

Photo: Hsieh Wen-hua, Taipei Times

“Could the rest of us also be published there as well?” Chung wondered.

Born in Japan to Taiwanese parents, Lin grew up in Beijing and did not return to Taiwan until the KMT retreat in 1949. In the book, Lin Hai-yin and her Publishing Career (林海音及其出版事業), Wang Shu-chen (汪淑珍) writes that Lin’s unique background allowed her to keep an open mind and see past identity to recognize good work.

“She was able to recognize the potential and talent in submissions, even if their prose and techniques were still raw,” Lin’s daughter Hsia Tzu-li (夏祖麗) writes in her biography.

“Not only did she choose to publish these works, she would quickly write letters of encouragement to these writers. That meant a lot to aspiring authors.”

Cloud Gate Dance Theatre founder Lin Hwai-min (林懷民) was also one of Lin Hai-yin’s beneficiaries. A 14-year-old Lin Hwai-min used the NT$30 he received for a story he wrote in 1961 to enroll in his first ballet class.

THE CAPTAIN INCIDENT

The 1950s were the height of the White Terror era, when anyone suspected of being subversive toward the government could be punished. Wang writes that Lin Hai-yin was treading dangerous ground by publishing works by local authors.

“She was a free spirit,” Chung Chao-cheng recalls. “She did not care about anti-communism or White Terror. She believed that she was pure and genuine. But free spirits often do not have enough political awareness.”

“I only knew that she was encouraging me, I had no idea that she was sitting on a chair of needles as editor of the supplement. Anything we sent to her could be troublesome,” Huang says. “She received a fixed salary, and she did not need to take such risks.”

In 1963, the 10th year of Lin’s tenure with the literary supplement, she finally ran afoul of the authorities. On April 23, 1963, she published the poem Story (故事), which depicted a ship captain who drifted to a small island and met a rich widow who kept him there, promising to fix his ship but never delivering.

“She gave him pearls, agate and lots of treasure, but his whiskers were graying and his sailors aging. He was oblivious to the fact that the real treasure was in his homeland.”

The authorities called the newspaper immediately and told the editor that “inappropriate materials appeared in your pages today.” They explained that the poem “alluded to the ignorance and foolishness of the president [Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石)].”

Lin Hai-yin quit her job immediately. She would later learn that the poem’s author, Feng Chi (風遲), was jailed for three years on suspicion of sedition. Feng Chi sought out Hsia 33 years later to apologize for the incident, adding that the poem was included in a book he published in 1998.

“In those days, something like this could either be nothing or something very serious,” Lin Hai-yin’s husband Ho Fan (何凡) says.

“As long as it was resolved without incident, we were happy. There’s a lot we can do. If we can’t do one thing, we can do something else.”

‘PURE LITERATURE’

In 1967, Lin Hai-yin founded Pure Literature Monthly (純文學月刊) and, in the next year, established Pure Literature, the first publishing company in Taiwan to focus exclusively on literature.

“Taiwan was still a rather closed society in 1968,” Hsia writes. “To publish only literature was not an easy feat, especially in that politically sensitive time. But she did it.”

Lin Hai-yin’s work spans essay collections, novels, children’s books and translations of Western works. Her most famous title, My Memories of Old Beijing (城南舊事), draws from her childhood experiences in China. She died on Dec. 1, 2001.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.