Cheng Tsung-lung’s (鄭宗龍) newest work for Cloud Gate 2 (雲門 2) about dreams, Dream Catcher (捕夢, is unusual from start to finish, but more like a tale from British author Neil Gaiman than an Alice in Wonderland flight of fancy.

Like most dreams, Cheng’s work follows a meandering path and you never know what is going to happen next. Nothing appears directly connected to what came before, though it was perhaps darker than what many people might have anticipated, given the title, and in the end, all you remember are specific fragments, moments in time, not the whole dream.

However, it is those moments that make the show.

Photo: CNA

The stage is completely exposed as the audience files into the Cloud Gate Theater in New Taipei City’s Tamshui District (淡水), light battens hanging down almost to the floor.

The bareness could reflect the emptiness of a bed before one goes to sleep, but in this case the dancers have to make their bed first, so to speak. The show starts with the battens being raised as 10 casually clad dancers quickly run down the right-side steps of the theater, carrying a long roll of furled stage drapes in their arms, which they then proceed to hang from rods on the side of the stage.

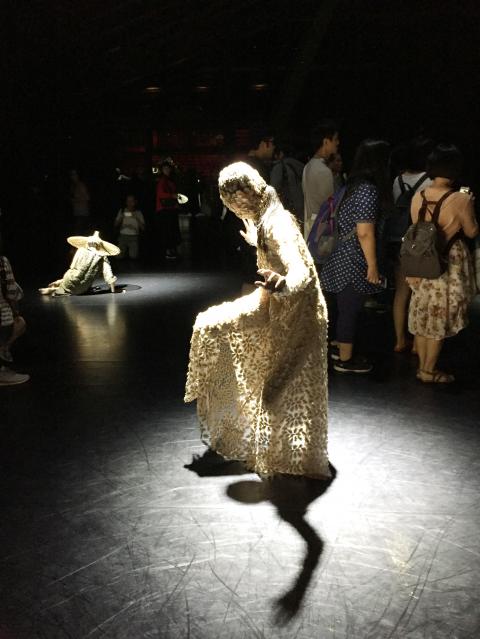

An electronic zap freezes the dancers in place and darkness descends. Hooded, cloaked figures gradually emerge out of the darkness. The cloaks are then gradually removed to reveal an assortment of mysterious figures, some faceless, some half-human-half-animal, some normal looking.

Photo: Diane Baker, Taipei Times

The costumes, by fashion designer and stylist Fan Huai-chih (范懷之), include an exquisite lace-embroidered gown, glittering sheer tops and pants, partial gorilla suits and one black pants outfit that would not look out of place on a red carpet appearance.

A long scroll of white paper drops from the rafters, hanging ominously like a giant test paper. Later it is torn apart, used as a wall, encases a body, becomes a costume and eventually laid out like a pathway to the end.

Cheng moves his dancers in and out of the shadows, thanks to the largely monochromatic work of lighting designer Shen Po-hung (沈柏宏), with lots of great solos that allowed their personalities to shine through — even if their faces are obscured — before ending with some group dancing.

Thankfully, the company’s program included small photographs of the cast, so that even if you couldn’t make out a face, in the end you could tell who danced what, like senior dancer Yang Ling-kai (楊淩凱), whose face was completely obscured by a giant conical farmer’s hat.

Most memorable, however, was the long solo by Lee Tzu-chun (李姿君), who used to dance with Cloud Gate Dance Theatre (雲門舞集) and stood out in Lee Hwai-min’s (林懷民) Listening to the River (聽河) in 2011 and How Can I Live On Without You (如果沒有你), among other works.

Starting from a pyramid-shaped opening in the back curtain, Lee slowly advanced to mid-stage, twisting and turning, hair flying; she just rocked to the music by Chinese-American composer Li Daiguo (李帶果).

Lee’s solo was followed by an interesting duet between her and a curly-locked Tsou Ying-lin (鄒瑩霖). The two women were always in touch with one another as they revolved and entwined around one another, connecting either head to head like conjoined twins or by another body part.

However, the entire cast was in fine form: Su I-chieh (蘇怡潔), Wu Jui-ying (吳睿穎), Hsu Chih-hen (許誌恆), Chan Hing-chung (陳慶翀), Huang Yung-huai (黃詠淮), Yeh Po-sheng (葉博聖) and Liao Chin-ting (廖錦婷).

The show does not end with a single curtain call. Somewhat unusually for a dance or theater company, Cloud Gate 2 encourages the audience not only to take photographs at the end of show by having the 10 performers placed around the stage in separate spot-lit circles, posing or dancing, but to to walk onto the stage floor so they can see the dancers and their costumes up close.

There are four more performances of Dream Catcher this weekend. Catch it if you can.

Late last month Philippines Foreign Affairs Secretary Theresa Lazaro told the Philippine Senate that the nation has sufficient funds to evacuate the nearly 170,000 Filipino residents in Taiwan, 84 percent of whom are migrant workers, in the event of war. Agencies have been exploring evacuation scenarios since early this year, she said. She also observed that since the Philippines has only limited ships, the government is consulting security agencies for alternatives. Filipinos are a distant third in overall migrant worker population. Indonesia has over 248,000 workers, followed by roughly 240,000 Vietnamese. It should be noted that there are another 170,000

Enter the Dragon 13 will bring Taiwan’s first taste of Dirty Boxing Sunday at Taipei Gymnasium, one highlight of a mixed-rules card blending new formats with traditional MMA. The undercard starts at 10:30am, with the main card beginning at 4pm. Tickets are NT$1,200. Dirty Boxing is a US-born ruleset popularized by fighters Mike Perry and Jon Jones as an alternative to boxing. The format has gained traction overseas, with its inaugural championship streamed free to millions on YouTube, Facebook and Instagram. Taiwan’s version allows punches and elbows with clinch striking, but bans kicks, knees and takedowns. The rules are stricter than the

“Far from being a rock or island … it turns out that the best metaphor to describe the human body is ‘sponge.’ We’re permeable,” write Rick Smith and Bruce Lourie in their book Slow Death By Rubber Duck: The Secret Danger of Everyday Things. While the permeability of our cells is key to being alive, it also means we absorb more potentially harmful substances than we realize. Studies have found a number of chemical residues in human breast milk, urine and water systems. Many of them are endocrine disruptors, which can interfere with the body’s natural hormones. “They can mimic, block

Pratas Island, or Dongsha (東沙群島) had lain off the southern coast of China for thousands of years with no one claiming it until 1908, when a Japanese merchant set up a facility there to harvest guano. The Americans, then overlords of the Philippines, disturbed to learn of Japanese expansion so close to their colony, alerted the Manchu (Qing) government. That same year the British government asked the Manchus who owned the island, which prompted the Manchu government to make a claim, according to South China Sea expert Bill Hayton. In 1909 the government of Guangdong finally got around to sending