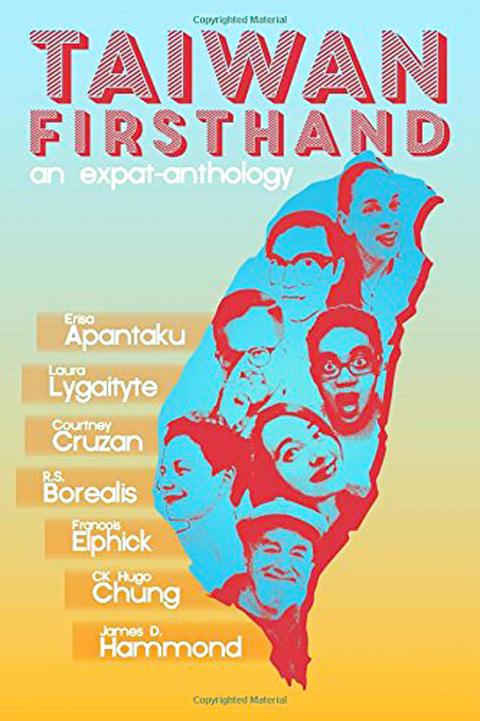

Why are Westerners almost routinely enthusiastic about Taiwan? On the surface, Taiwan Firsthand is a collection of essays by Westerners (with one exception) writing about their experiences here. But in fact the entire book is a sustained peon of praise for everything Taiwanese — the people, the food, medical treatment and even the postal services. There’s hardly a critical word in it.

Whether it’s a Lithuanian, a South African, or a citizen of the US or the UK, there’s not a trace of outright hostility, apart from a couple of jokey references to over-inquisitiveness about income and marital status.

Among the most striking features of the book are the comparisons with China. Courtney Cruzan lived in Ningbo in China’s Zhejiang Province before moving to Taipei, and she compares Taiwan’s cleanliness, orderliness, friendliness and freshness with her frequent experience across the Strait of shouting, muscling through crowds and elbowing your way to your rightful seat. To a long list of virtues, she adds Taiwanese respect for individuality, international awareness and the fact that a visit to a doctor here cost her only US$8, including the prescription — something quite extraordinary for an American.

The praise, however, doesn’t just stop at Taiwan. The above writer, for instance, writes about an epiphany in a Taipei showroom in which she praises the virtues of the East in general. Learning through meditation and the like to accept the world as it is, surrender, trust and open up. She’s not the only writer here to go deep below the surface.

Canada’s R.S. Borealis, for example, went to a Taipei clairvoyant and was astounded to be told she had a special relationship with her brother. This brother, who the seer had only seen in a photo, had in fact proposed that the two of them live together and adopt a child. The clairvoyant even asked her if she had ever considered marrying her brother.

Borealis also writes vividly about knife massage and mentions that she has the Chinese name Kuibeike Waixing Wushi (the alien witch from Quebec), though her Canadian name is actually Raja. She specializes in lecturing on aliens and meteorites, often with comedy added.

“Coming to Taiwan is the best choice I ever made,” Borealis says.

The one exception to the pan-expat contributors is C.K. Hugo Chung. He was born here and has come back after many years living in the US. He makes the ingenious comparison between coming to accept himself as Taiwanese (as opposed to being a citizen of the Republic of China) and coming to accept the fact that he’s gay. The metaphorical link here is between his mother and his mother country, though in reality his actual mother apparently never accepted his sexual orientation, considering it a choice he’s made rather than an unalterable condition. He learned to be himself most fully, he writes, in New York.

Chung is well known from short-story anthologies such as Taiwan Tales and Night Market (reviewed in the Taipei Times on March 19 and Sept. 24, 2015 respectively). His first writing collection, Writeous Accents, is due out early next year.

Then we have Erisa Apantatu, originally from Chicago. She taught in a bilingual school in Keelung, then became involved in writers’ workshops and filmmakers’ groups in Taipei and also visited the outlying island of Kinmen for a sports contest that involved extensive cycling. She joins several others in praising the food and writes that it is incredibly safe for foreigners here.

Laura Lygaityte is from Lithuania and came to Taiwan in 2011. (She says, incidentally, that Lithuania is three times bigger than Taiwan whereas it’s closer to twice as large). She works in an art gallery, and was recognized as such even on holiday on Orchid Island. Her boss is international, sophisticated and professional, she writes. She objects to the allegedly Taiwanese habit of pointing at people (supposedly considered rude back home), but this is one of her very few objections.

Then there’s Francois Elphick from South Africa, who works in design. He has left three cellphones in taxis and gotten them all back, he says. “Famous,” “inconvenient” and “embarrassed” are the three most commonly-used adjectives in Taiwan, he adds. Like most of the other writers, he has some amusing things to say about learning Chinese. Tones in Chinese are what gendered nouns are in French, he quips, a cunning device to prevent foreigners from ever becoming genuine native speakers.

Finally comes James Hammond from the UK, who was educated at Cambridge University. He’s been living here since 1986 — 31 wonderful years, he says. He’s a comic as well as a former worker in the semiconductor and laser industries. Back in the UK, his first wife got re-married to a bookkeeper.

“No accounting for tastes,” he says.

He ends his piece, and the book, with this heart-felt endorsement: “The people of this wonderful Isla Formosa are the most genuinely kind, genuinely generous and genuinely honest in my humble opinion, of all the peoples of Asia.”

You can’t get much more approving than that.

So, what’s the reason for all this Occidental enthusiasm? It seems unlikely that Filipinos, say, would see things this way. They come to Taiwan mostly as domestic helpers, after all, and would probably put astonishment at the amount of money Taiwanese earn at the forefront of their impressions. Presumably Westerners share this affluence, and so perceive other virtues, genuine as I’m sure they are, as icing on the cake. This, anyway, is what this handy little book, ecstatic though it is, silently suggests.

That US assistance was a model for Taiwan’s spectacular development success was early recognized by policymakers and analysts. In a report to the US Congress for the fiscal year 1962, former President John F. Kennedy noted Taiwan’s “rapid economic growth,” was “producing a substantial net gain in living.” Kennedy had a stake in Taiwan’s achievements and the US’ official development assistance (ODA) in general: In September 1961, his entreaty to make the 1960s a “decade of development,” and an accompanying proposal for dedicated legislation to this end, had been formalized by congressional passage of the Foreign Assistance Act. Two

Despite the intense sunshine, we were hardly breaking a sweat as we cruised along the flat, dedicated bike lane, well protected from the heat by a canopy of trees. The electric assist on the bikes likely made a difference, too. Far removed from the bustle and noise of the Taichung traffic, we admired the serene rural scenery, making our way over rivers, alongside rice paddies and through pear orchards. Our route for the day covered two bike paths that connect in Fengyuan District (豐原) and are best done together. The Hou-Feng Bike Path (后豐鐵馬道) runs southward from Houli District (后里) while the

March 31 to April 6 On May 13, 1950, National Taiwan University Hospital otolaryngologist Su You-peng (蘇友鵬) was summoned to the director’s office. He thought someone had complained about him practicing the violin at night, but when he entered the room, he knew something was terribly wrong. He saw several burly men who appeared to be government secret agents, and three other resident doctors: internist Hsu Chiang (許強), dermatologist Hu Pao-chen (胡寶珍) and ophthalmologist Hu Hsin-lin (胡鑫麟). They were handcuffed, herded onto two jeeps and taken to the Secrecy Bureau (保密局) for questioning. Su was still in his doctor’s robes at

Mirror mirror on the wall, what’s the fairest Disney live-action remake of them all? Wait, mirror. Hold on a second. Maybe choosing from the likes of Alice in Wonderland (2010), Mulan (2020) and The Lion King (2019) isn’t such a good idea. Mirror, on second thought, what’s on Netflix? Even the most devoted fans would have to acknowledge that these have not been the most illustrious illustrations of Disney magic. At their best (Pete’s Dragon? Cinderella?) they breathe life into old classics that could use a little updating. At their worst, well, blue Will Smith. Given the rapacious rate of remakes in modern