As anyone who visited or lived in Taipei back in the early 1990s or before will know, the metropolis (and its surrounding satellites) have undergone an amazing, almost unrecognizable transformation over the last 20 years. However, no part has changed more startlingly than New Taipei City’s Sijhih District (汐止), on the Keelung River about halfway between Taipei City and Keelung.

In the past, this low-lying area (the name means “limit of the tide,” since it lies at the upper limit of the tidal Keelung River) was once prone to suffering flood damage, a dubious reputation that came to a dramatic head with astounding TV footage of local houses under as much as one story of floodwater, following the deluge dumped on northern Taiwan by Typhoon Nari in 2001.

Photo: Richard Saunders

Following the disaster, a levee built along the river in 2002, and the completion of Yuanshanzi Flood Diversion Tunnel (圓山子分洪道) in 2005, finally rid the area of its curse, and these days Sijhih has undergone a major facelift, with modern high-rise office and apartment blocks much to the fore. The dramatic improvement in the district’s fortunes in recent years might not be a compelling reason to pay it a visit by itself, but its environs are rich in beautiful scenery, including one of New Taipei City’s most enchanting natural lakes, a smattering of shapely summits, three sets of waterfalls and several extraordinary curiosities.

Most hikers take the train to Sijhih to climb the deceptively easy-looking eminence known — for reasons not at first apparent — as Dajian Mountain (大尖山), and it’s a very worthwhile hike. If you cheat and take the minibus part of the way up, the hike can be completed in a couple of hours, but the trip can be lengthened into a full day by heading southeast across the hills to New Taipei City’s Pingsi District (平溪) along a network of undeveloped dirt trails (bring a map).

For a much shorter hike, walk (or take a minibus) up to Tiansiou Temple (天秀宮), passing close to the extraordinary temple of Zihhang Tang (慈航堂), and climb to the summit of Dajian Mountain via the beautiful Sioufong Waterfall (秀峰瀑布).

If you start the hike at Sijhih train station, walk south (away from the river) to the main road through the district (highway 5), turn right and then left onto Sioufong Road (秀峰路), which climbs up to Tiansiou Temple and the trailhead nearby. It’s a long and fairly dull climb.

An easier alternative is to take the F911 minibus service that leaves from Sijhih Park (汐止公園; close to the train station) every hour or so and shuttles passengers almost all the way to Tiansiou Temple, near the trailheads to both Sioufong Waterfall and Dajian Mountain. From here it’s just over an hour’s climb via the waterfall to the summit.

Pray for a heavy downpour before climbing Dajian Mountain. The deluge won’t affect the quality of the wide, stepped paths too much, but it will make one of the scenic highlights of the walk, Sioufong Waterfall, worth seeing.

Set in a deep, rocky ravine on the side of the steep ridge above Sijhih, the waterfall makes a fine show as it glides down a steep rock face eroded with countless crinkly serrations that give it a distinctive appearance, but in dry weather it dries up almost completely.

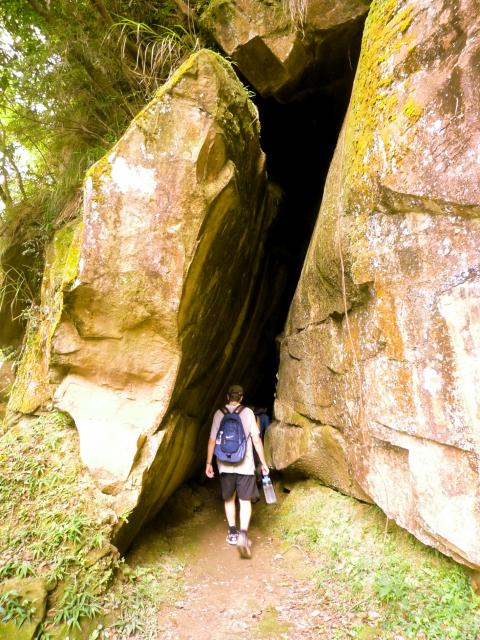

If the waterfall fails to impress, there’s the Dragon Boat Cave (a tall, narrow, crack-like cavern through which the path passes) to enjoy en route. To get to the waterfall, follow the road past Tiansiou Temple, and a few minutes after it, at a sharp bend, take the signposted trail on the right.

From Sioufong Waterfall, a stepped path climbs to the road above, and a few meters further uphill another path leaves the road and heads straight up the steep, darkly wooded upper slopes of Dajian Mountain: a short but steep trudge. At the top, turn left to a wooden ornamental rain shelter to claim your reward: a remarkable, bird’s eye view of Sijhih, laid out along the valley of the Keelung River directly below, looking west towards Taipei in the distance.

More visually appealing is the panorama across to Yangmingshan (陽明山) and Guanyin Mountain (觀音山) ahead, and, to the right, the twin pyramids of Keelung Mountain (基隆山) and Peace Island (和平島), looming out of the East China Sea and presenting an especially sharp and impressive profile from this distant vantage point.

If you walk the entire distance from Sijhih train station, pay your respects on the way at one of Taiwan’s more unique temples. Turn left off Sioufong Road beside a brightly colored temple three hundred meters south of highway 5, and follow this lane as it climbs stiffly to an enormous new temple complex at the top (a 10-minute climb from the junction.)

This is the very handsome temple of Zihhang Tang. Walk up through the fine temple complex to the pagoda at the top. Inside the figure covered in gold leaf and protected by a glass case, is the incorruptible (mummified) body of a former monk, who died in 1943. It’s said to be one of three such incorruptible corpses in Taiwan, but this is the most famous, and an object of veneration for countless Buddhists.

Richard Saunders is a classical pianist and writer who has lived in Taiwan since 1993. He’s the founder of a local hiking group, Taipei Hikers, and is the author of six books about Taiwan, including Taiwan 101 and Taipei Escapes. Visit his Web site at www.taiwanoffthebeatentrack.com.

We lay transfixed under our blankets as the silhouettes of manta rays temporarily eclipsed the moon above us, and flickers of shadow at our feet revealed smaller fish darting in and out of the shelter of the sunken ship. Unwilling to close our eyes against this magnificent spectacle, we continued to watch, oohing and aahing, until the darkness and the exhaustion of the day’s events finally caught up with us and we fell into a deep slumber. Falling asleep under 1.5 million gallons of seawater in relative comfort was undoubtedly the highlight of the weekend, but the rest of the tour

Youngdoung Tenzin is living history of modern Tibet. The Chinese government on Dec. 22 last year sanctioned him along with 19 other Canadians who were associated with the Canada Tibet Committee and the Uighur Rights Advocacy Project. A former political chair of the Canadian Tibetan Association of Ontario and community outreach manager for the Canada Tibet Committee, he is now a lecturer and researcher in Environmental Chemistry at the University of Toronto. “I was born into a nomadic Tibetan family in Tibet,” he says. “I came to India in 1999, when I was 11. I even met [His Holiness] the 14th the Dalai

Following the rollercoaster ride of 2025, next year is already shaping up to be dramatic. The ongoing constitutional crises and the nine-in-one local elections are already dominating the landscape. The constitutional crises are the ones to lose sleep over. Though much business is still being conducted, crucial items such as next year’s budget, civil servant pensions and the proposed eight-year NT$1.25 trillion (approx US$40 billion) special defense budget are still being contested. There are, however, two glimmers of hope. One is that the legally contested move by five of the eight grand justices on the Constitutional Court’s ad hoc move

Stepping off the busy through-road at Yongan Market Station, lights flashing, horns honking, I turn down a small side street and into the warm embrace of my favorite hole-in-the-wall gem, the Hoi An Banh Mi shop (越南會安麵包), red flags and yellow lanterns waving outside. “Little sister, we were wondering where you’ve been, we haven’t seen you in ages!” the owners call out with a smile. It’s been seven days. The restaurant is run by Huang Jin-chuan (黃錦泉), who is married to a local, and her little sister Eva, who helps out on weekends, having also moved to New Taipei