Aug. 21 to Aug. 27

Paulus Traudenius was not a subtle man. In August of 1641, the Dutch governor of Formosa sent a letter to his Spanish counterpart in Keelung with intentions laid bare in the first sentence:

“I have the honor to communicate to you that I have received the command of a considerable naval and military force with the view of making me master by civil means or otherwise of the fortress Santissima Trinidad in the isle of Ke-lung (Keelung) of which your Excellency is the Governor.”

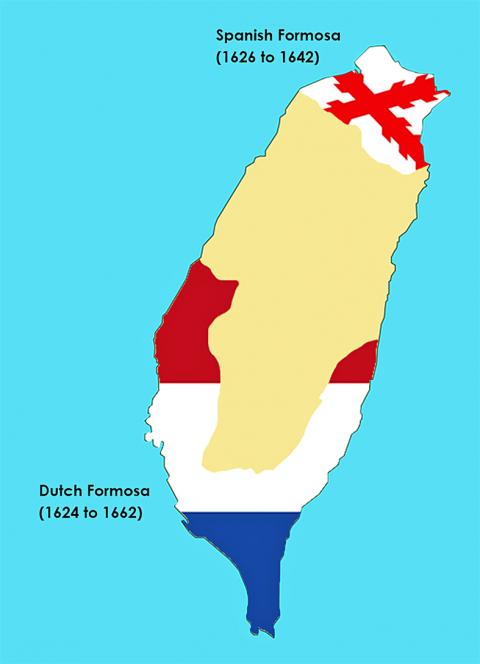

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Gonzalo Portillo, the Spanish governor, did not take this kindly, responding with:

“I have the honor to point out to you that as becomes a good Christian who recalls the oath he has made before his king, I cannot and will not surrender the forts demanded by your Excellency, as I and my garrison have determined to defend them.”

And indeed he did, defeating Traudenius’ forces and sending them back to their base Fort Zeelandia (present-day Tainan). But the Dutch returned with a much larger force a year later, taking both Tamsui and Keelung. The Spanish officially surrendered on Aug. 26, 1642.

Graphic: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

“So great was the the joy at their victory that the Dutch celebrated it for eight days,” writes James Davidson in his 1903 book, The Island of Formosa, Past and Present.

COLLISION COURSE

It was a collision of two colonial powers who had substantial territories in Asia — the Dutch were based in present-day Indonesia and the Spanish in the Philippines. It was an extension of bad blood in their respective h omelands as the Eighty Years’ War raged on between the Netherlands and Spain.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Portugal became involved after the union of the Spanish and Portuguese crowns, and the conflict extended overseas with the Dutch trying to take over Spanish and Portuguese colonies around the world.

Given this background, it’s not surprising that just two years after the Dutch built Fort Zeelandia in 1624, the Spanish established their fort in Keelung with the specific aim of protecting Spanish and Portuguese interests. Jose Eugenio Borao Mateo writes in The Spanish Experience in Taiwan, 1626-1642 that the Dutch were using Taiwan to “harass the Fujian-Manila trade.”

Peter Nuyts, who held Traudenius’ position from 1627 to 1629, had already petitioned the Dutch East India Company headquarters in present-day Jakarta to send an expedition to get rid of the Spanish.

In addition to warning about the danger of a Spanish expedition and their presence diverting trade from Fort Zeelandia, Nuyts also wrote: “If they are once firmly established, it is to be feared that they may incite the Chinese and the natives to revolt against us.”

The authorities’ response is not known, but Keelung was left in peace for another 12 years until Traudenius took matters into his own hands.

It should be noted that this was not the only instance of Dutch aggression against Spanish and Portuguese territories during this period. They blockaded Goa in 1639 and successfully captured Malacca in 1641.

KEELUNG UNDER The DUTCH AND SPANISH

It’s easy to simplify matters by just stating that the “Spanish established a fort in Keelung in 1626” and “the Dutch kicked them out in 1642.”

But obviously, that area was already inhabited by Aborigines and probably a handful of Han Chinese. Borao provides some details of the Spanish invasion in his book, stating that the colonizers landed on May 10, and six days later a ceremony symbolizing “the possession of the port of (Keelung) and this fort (to be constructed), representing all the things of that island.”

When the inhabitants “refused to render obeisance to the King,” the Spaniards “took possession in the best form and manner that can be lawfully allowed.”

Borao writes that this meant chasing them from their villages and seizing their houses and belongings through “a show of might” while many residences were razed and burnt. The Spaniards promised to pay the Aborigines for the damages, but in four years had only given them just over 10 percent of the promised amount. There was still much unrest, which made them reluctant to keep paying.

According to Borao, the Spanish did not ask for tribute from the Aborigines “because in practice they did not consider the natives as vassals, but as heathens to be converted, neighbors and service suppliers.” He argues that the 1636 killing of several Spanish soldiers and a missionary in Tamsui was not due to tribute but simply from growing enmity.

The Ministry of Culture’s Encyclopedia of Taiwan entry states that overall, although the Spanish used Keelung as a base for military expeditions throughout northern Taiwan, its “colonial might was rather weak and they were not able to successfully suppress the resentment of the Aborigines.”

As for the Dutch, Davidson writes that they rapidly expanded their influence to the fertile plains south of Keelung, and by 1648 they counted 47 villages under their control in the area.

One of the first acts upon taking northern Taiwan, aside from increasing fortifications, was to send a clergyman to Tamsui “to look after the spiritual welfare of the natives.”

The Dutch did demand tribute. Davidson writes that “the [Dutch East India] company received considerable revenue from taxation, and it does not appear that much was paid out for the benefit of the island.”

They also influenced local demographics by encouraging and assisting with migration from China, resulting in the first large-scale arrival of Han Chinese over several decades.

The colony flourished, although not without unrest, until Ming Dynasty loyalist and military commander Koxinga, also known as Cheng Cheng-kung (鄭成功), captured Fort Zeelandia in 1661. The Dutch actually recaptured Keelung in 1664 — but abandoned it in 1668 due to local resistance and lack of profit.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

This is the year that the demographic crisis will begin to impact people’s lives. This will create pressures on treatment and hiring of foreigners. Regardless of whatever technological breakthroughs happen, the real value will come from digesting and productively applying existing technologies in new and creative ways. INTRODUCING BASIC SERVICES BREAKDOWNS At some point soon, we will begin to witness a breakdown in basic services. Initially, it will be limited and sporadic, but the frequency and newsworthiness of the incidents will only continue to accelerate dramatically in the coming years. Here in central Taiwan, many basic services are severely understaffed, and

Jan. 5 to Jan. 11 Of the more than 3,000km of sugar railway that once criss-crossed central and southern Taiwan, just 16.1km remain in operation today. By the time Dafydd Fell began photographing the network in earnest in 1994, it was already well past its heyday. The system had been significantly cut back, leaving behind abandoned stations, rusting rolling stock and crumbling facilities. This reduction continued during the five years of his documentation, adding urgency to his task. As passenger services had already ceased by then, Fell had to wait for the sugarcane harvest season each year, which typically ran from

It is a soulful folk song, filled with feeling and history: A love-stricken young man tells God about his hopes and dreams of happiness. Generations of Uighurs, the Turkic ethnic minority in China’s Xinjiang region, have played it at parties and weddings. But today, if they download it, play it or share it online, they risk ending up in prison. Besh pede, a popular Uighur folk ballad, is among dozens of Uighur-language songs that have been deemed “problematic” by Xinjiang authorities, according to a recording of a meeting held by police and other local officials in the historic city of Kashgar in

It’s a good thing that 2025 is over. Yes, I fully expect we will look back on the year with nostalgia, once we have experienced this year and 2027. Traditionally at New Years much discourse is devoted to discussing what happened the previous year. Let’s have a look at what didn’t happen. Many bad things did not happen. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) did not attack Taiwan. We didn’t have a massive, destructive earthquake or drought. We didn’t have a major human pandemic. No widespread unemployment or other destructive social events. Nothing serious was done about Taiwan’s swelling birth rate catastrophe.