Onions, tangerines and mugwort are not what usually comes to mind when one thinks about making paper, but they are among the many ingredients that visitors can experiment with at Taipei’s Suho Paper Memorial Museum (樹火紀念紙博物館), which hosts regular workshops to let people see paper as more than just something used to write or draw on.

These ingredients are among the stars of this year’s “Paper Seasoning” workshops, where participants use various edible materials in the papermaking process. The material is chosen according to both seasonal and cultural factors — Saturday’s class will feature tangerines because they are in season, while mugwort is the ingredient for June due to Dragon Boat Festival, when the herb is hung over doors to ward off evil spirits.

Museum education planner Suzi Hsu (許書慈) says that one can often gain more out of making something than simply using it as a tool.

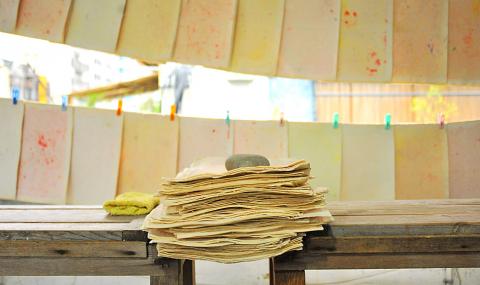

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

“We are used to simply purchasing paper as an end product, but we don’t understand the value of it,” she says. “Paper can also be perceptual and conceptual.”

Hsu used lots of paper as a former art student, but she never saw it as more than just a canvas for her creations. Now she appreciates the beauty of paper — down to the tiniest fiber.

“Most people see paper as a surface,” she says. “But when you rip a piece of paper apart, you will see the individual fibers. That’s the smallest, most captivating unit.”

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

She adds that even though these fibers bond together strongly, they are quite tolerant to additional materials. For example, while not fibrous enough to make paper alone, tangerine pulp, peels and leaves can be added to the paper mix to form different textures and patterns, and even aroma and color.

“We don’t want everyone to make the same piece of paper,” Hsu says. “We’ll teach techniques that allow a certain degree of flexibility, so the end product is more like a small painting.”

GOING LOCAL

Photo courtesy of Suho Paper Memorial Museum

The museum has also placed a focus on local products this year. April and May’s workshops will focus on wheat, a crop that has experienced a revival in the past few years.

Hsu says they have made paper with wheat grains and mash received from breweries, and they are looking at even more applications for the upcoming workshops.

While the Paper Seasoning workshop is suitable for all ages, Hsu says they also hold classes that are geared toward different groups — such as an interactive “Yoga Art for Parent and Child” class and also a more introspective tea and calligraphy session for adults, where the main goal is to relax the mind. There will also be a fan dyeing session in the summer.

Aside from the workshops, regular visitors can purchase an activity package (NT$200) where they can experience silk screening, ink rubbing and crafting a notebook from selected papers (including ones made from pineapple leaves). For an additional NT$80, they can make their own paper.

The museum’s regular exhibit takes visitors through the history of papermaking and its many appearances and applications — from audio speakers to electric insulation to cleaning up after using the toilet. The special exhibit, which runs through June 3, is Blank Texture, consisting of a space created with five different types of white paper. Visitors are encouraged to leave their phones behind and look within. Pamphlets that profess to teach calmness, known as “Meditation Guides,” are also provided as part of the exhibit.

May 26 to June 1 When the Qing Dynasty first took control over many parts of Taiwan in 1684, it roughly continued the Kingdom of Tungning’s administrative borders (see below), setting up one prefecture and three counties. The actual area of control covered today’s Chiayi, Tainan and Kaohsiung. The administrative center was in Taiwan Prefecture, in today’s Tainan. But as Han settlement expanded and due to rebellions and other international incidents, the administrative units became more complex. By the time Taiwan became a province of the Qing in 1887, there were three prefectures, eleven counties, three subprefectures and one directly-administered prefecture, with

Taiwan Power Co (Taipower, 台電) and the New Taipei City Government in May last year agreed to allow the activation of a spent fuel storage facility for the Jinshan Nuclear Power Plant in Shihmen District (石門). The deal ended eleven years of legal wrangling. According to the Taipower announcement, the city government engaged in repeated delays, failing to approve water and soil conservation plans. Taipower said at the time that plans for another dry storage facility for the Guosheng Nuclear Power Plant in New Taipei City’s Wanli District (萬里) remained stuck in legal limbo. Later that year an agreement was reached

What does the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) in the Huang Kuo-chang (黃國昌) era stand for? What sets it apart from their allies, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT)? With some shifts in tone and emphasis, the KMT’s stances have not changed significantly since the late 2000s and the era of former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九). The Democratic Progressive Party’s (DPP) current platform formed in the mid-2010s under the guidance of Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文), and current President William Lai (賴清德) campaigned on continuity. Though their ideological stances may be a bit stale, they have the advantage of being broadly understood by the voters.

In a high-rise office building in Taipei’s government district, the primary agency for maintaining links to Thailand’s 108 Yunnan villages — which are home to a population of around 200,000 descendants of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) armies stranded in Thailand following the Chinese Civil War — is the Overseas Community Affairs Council (OCAC). Established in China in 1926, the OCAC was born of a mandate to support Chinese education, culture and economic development in far flung Chinese diaspora communities, which, especially in southeast Asia, had underwritten the military insurgencies against the Qing Dynasty that led to the founding of