The first thing that needs to be stated about this excellent book is how well it’s written. There’s not a shred of academic jargon here. Absent, too, are tiresome references to other people’s research in parentheses to support every statement. Should you notice these things at the start, you’d be right in seeing in them a foretaste, even a guarantee, of the straightforwardness and honesty of what is to come. Accidental State, in other words, is a pleasure to read, and of how many academic books these days can that be said?

You might think that Lin Hsiao-ting’s (林孝庭) credentials, which include Oxford, Stanford, National Taiwan University and Harvard (his publisher here), would guarantee these qualities. Unfortunately no university these days is immune to the infection of dreary academic convention, so that Lin deserves credit for these shining virtues entirely in his own right.

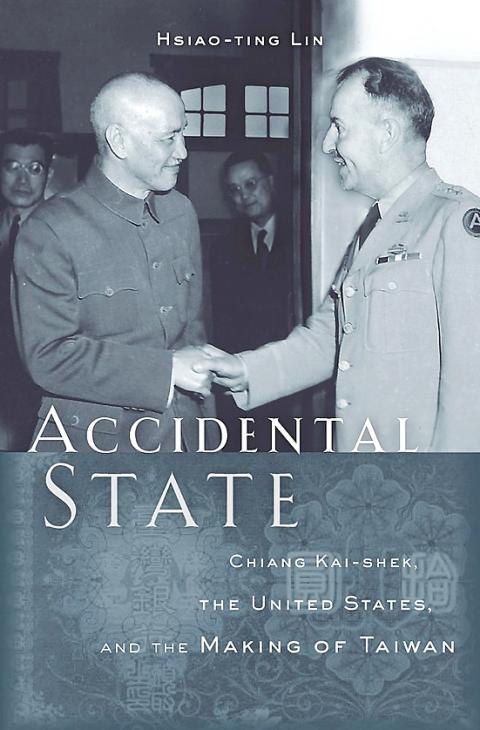

The book looks at the first few years of Taiwan’s history under the rule of Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石). What it argues is that the popular view that the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) migrated here en masse in late 1949, and then ruled the country with US support, overlooks many complicating subtleties, some revealed in documents — KMT archives, ROC official files, personal papers of some top Taiwanese leaders, British documents — only recently made public.

First, Chiang didn’t immediately see Taiwan as the only territory he could fall back on — there were enclaves in China where the KMT was still in control, notably Hainan Island, an area of Myanmar bordering on Yunnan and many off-shore islands, and these all held out possibilities. Secondly, the US wasn’t immediately convinced of Chiang’s viability for support, and some of its diplomatic initiatives were the work of individuals on the ground working quasi-independently. Thirdly, Chiang was encountering serious difficulties with other senior KMT personnel, some of whom refused to obey his orders. He wasn’t, in other words, the undisputed KMT leader in Taipei until after the US government finally decided he was the best channel through which to donate arms and funds.

Of the individuals acting semi-independently in Taiwan, by far the most important looked at in this book is Charles Cooke, a retired US admiral. Not only was he responsible for having surplus US gasoline and ammunition from Japan sold to Chiang at preferential prices but, much more importantly, his advice was crucial in persuading the Nationalists to abandon both Hainan Island and the Zhoushan Islands in the spring of 1950.

This was all only months after US president Harry Truman had announced at a press conference on Jan. 5, 1950 that there would be no US involvement in the Chinese Civil War — something that had, in the eyes of a many observers, effectively already finished — and that there would be no US assistance or advice given to the Nationalists on Taiwan.

THE REDS ARE COMING

What dramatically changed Washington’s attitudes was Beijing’s pact with Moscow of February 1950, four months before the outbreak of the Korean War on June 25. This treaty, together with a successful Soviet atomic bomb test in August 1949, made it suddenly seem as if communism was an international movement capable of expanding both into Europe and into East Asia. Should Soviet forces ever begin to operate out of Taiwan, for instance, their extension eastwards to Japan and southward to the Philippines, and then the rest of the Pacific, would be hard to counteract. And so it was that, on June 27, 1950, only three days after the outbreak of war in Korea, Truman announced that he had ordered the Seventh Fleet into the waters between Taiwan and China.

Even so, tensions between Chiang and the US continued. Washington rejected Chiang’s offer of 33,000 of his best troops to fight alongside UN forces in Korea (on the grounds of the legitimacy any acceptance would give to the status of Taiwan), and Chiang disagreed with the US preference for a Nationalist attempt to retake Hainan Island after it was lost to the Communists (though he later appeared to change his mind), opting instead for raids on the Fujian and Zhejiang coasts with the unadvertised support of the CIA.

The Nationalist enclave in northern Myanmar under Li Mi (李彌), which had made some disastrous forays into Yunnan Province, and some 23,000 Nationalists interned by the French in Indochina, were both finally brought back to Taipei, leaving the coastal raids all that remained of the grand project of re-taking China. A secret Japanese organization aiming to train the Nationalists on Taiwan, largely ignored by scholars according to the author, is also discussed.

Chiang, this book implies, never really envisaged a full-scale assault on the Chinese mainland, but used plans for such a contingency as part of his negotiation strategy with Washington. Finally, on Dec. 2, 1954, a mutual defense treaty between the US and the Republic of China (ROC) was signed. Its provision that US approval was necessary before any invasion of the mainland was attempted, however, was not revealed, so as not to shatter the hopes of the Taiwanese population.

What this book argues, then, is that the various forces involved stumbled towards the eventual situation whereby Taiwan effectively became what Lin calls a “client state” of the US. Initially, Chiang was considering other possibilities, the US remained unconvinced and the KMT itself was divided. Everyone acknowledges that what changed everything was the Korean War, which persuaded the US that Taiwan was crucial to the East Asian balance of power.

What Lin does in this fine book is examine the confused situation that existed from 1949 to 1954, leading up to the KMT’s realization that the game was up in China and the decision by the Americans to finally sign a formal treaty with Taipei. The security of Taiwan, the “accidental state” of the book’s title, and Chiang’s predominance therein, were both from that moment assured.

It’s a good thing that 2025 is over. Yes, I fully expect we will look back on the year with nostalgia, once we have experienced this year and 2027. Traditionally at New Years much discourse is devoted to discussing what happened the previous year. Let’s have a look at what didn’t happen. Many bad things did not happen. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) did not attack Taiwan. We didn’t have a massive, destructive earthquake or drought. We didn’t have a major human pandemic. No widespread unemployment or other destructive social events. Nothing serious was done about Taiwan’s swelling birth rate catastrophe.

Words of the Year are not just interesting, they are telling. They are language and attitude barometers that measure what a country sees as important. The trending vocabulary around AI last year reveals a stark divergence in what each society notices and responds to the technological shift. For the Anglosphere it’s fatigue. For China it’s ambition. For Taiwan, it’s pragmatic vigilance. In Taiwan’s annual “representative character” vote, “recall” (罷) took the top spot with over 15,000 votes, followed closely by “scam” (詐). While “recall” speaks to the island’s partisan deadlock — a year defined by legislative recall campaigns and a public exhausted

In the 2010s, the Communist Party of China (CCP) began cracking down on Christian churches. Media reports said at the time that various versions of Protestant Christianity were likely the fastest growing religions in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The crackdown was part of a campaign that in turn was part of a larger movement to bring religion under party control. For the Protestant churches, “the government’s aim has been to force all churches into the state-controlled organization,” according to a 2023 article in Christianity Today. That piece was centered on Wang Yi (王怡), the fiery, charismatic pastor of the

Hsu Pu-liao (許不了) never lived to see the premiere of his most successful film, The Clown and the Swan (小丑與天鵝, 1985). The movie, which starred Hsu, the “Taiwanese Charlie Chaplin,” outgrossed Jackie Chan’s Heart of Dragon (龍的心), earning NT$9.2 million at the local box office. Forty years after its premiere, the film has become the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute’s (TFAI) 100th restoration. “It is the only one of Hsu’s films whose original negative survived,” says director Kevin Chu (朱延平), one of Taiwan’s most commercially successful