A Star Wars-inspired organization has failed to use the force of its arguments to convince the charity watchdog that it should be considered a religious organization.

The Temple of the Jedi Order, members of which follow the tenets of the faith central to the Star Wars films, sought charitable status earlier this year, but the Charity Commission has ruled that it does not meet the criteria for a religion under UK charity law.

In a ruling that saw lawyers scrutinizing the precise nature of Jediism and the force, the power that Jedi believe underpins the universe, the commission wrote that Jediism “lacks the necessary spiritual or non-secular element” it was looking for in a religion.

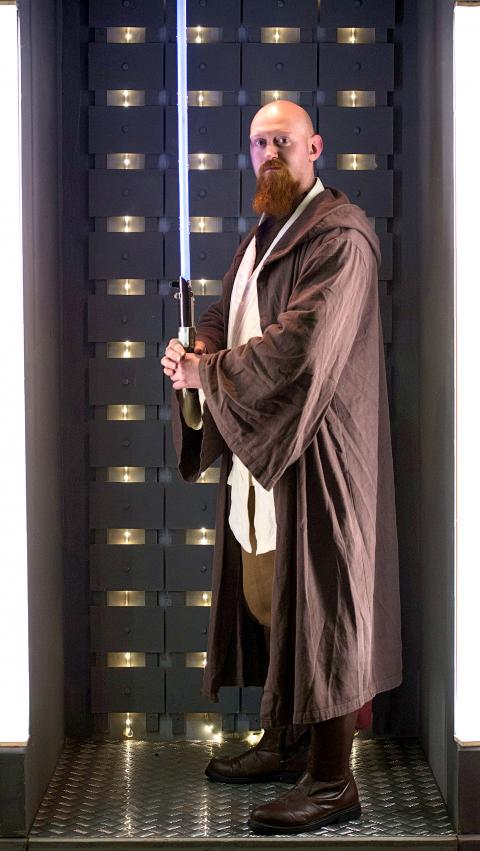

Photo: AFP/OLI SCARFF

The Temple of the Jedi Order, the commission noted, was an “entirely Web-based organization and the Jedi are predominantly, if not exclusively, an online community.” There was “insufficient evidence that moral improvement is central to the beliefs and practices of [the group].”

The doctrine promoted by the group borrowed widely from other world religions and philosophies, but “the commission does not consider that the aggregate amounts to a sufficiently cogent and distinct religion,” it said, adding that Jediism is highly permissive, with many different interpretations possible.

Kenneth Dibble, the Charity Commission’s chief legal adviser, said: “The meaning of ‘religion’ in charity law has developed over many years and now encompasses a wide range of belief systems.

“The decisions which the commission makes on the extent of this meaning can be difficult and complex, but are important in maintaining clarity on what is, and is not, charitable.”

The Temple of the Jedi Order, based in Beaumont, Texas, is recognized as a charitable or non-profit group by the US Internal Revenue Service.

Last year, the charity regulator in New Zealand rejected an application by another group for Jediism to be considered a religion for charitable purposes.

The Temple’s Web site says it promotes “goodwill, understanding, compassion and serenity”.

“We do not teach mystical powers or how to build lightsabers, we are not a dedicated Star Wars fan site, we are not affiliated with George Lucas or Disney and we are not for people who just want to wear a badge reading ‘I’m a Jedi,’” it says.

Brenna Cavell, 32, a psychologist and spokeswoman for the Temple, said the group was disappointed by the charity commission’s decision. “We put a lot of work into the application and really did our best to illustrate why we do consider ourselves a religion and why we believe we do offer benefits not just to our members but also to the public at large,” she said.

The group had made the application to ensure that people who donate money towards the Temple’s upkeep “have a sense of the legitimacy, that we do take it seriously and that any money that they do give to us is properly stewarded,” she said.

Cavell said the Temple of the Jedi Order was inspired by the philosophy that underpins the Star Wars universe, which is itself inspired by the work of mythologist Joseph Campbell, rather than by the movies themselves. “It’s not based on worshipping of the force or George Lucas, although many of our members refer to a higher power or the transcendent as the force. But you could easily exchange it for God, the universe — it’s the same thing to us, we just happened to pick that name.”

In the UK, Jedi has been the most popular alternative religion in two consecutive editions of the census, after a national campaign saw more than 390,000 people (0.7% of the population) describe themselves as Jedi Knights on the 2001 census. Numbers fell sharply a decade later, but there were still 176,632 people who told the government they were Jedi Knights.

The Temple of the Jedi Order could not provide figures on how many active members it has in the UK. Cavell said around 30,000 people have accounts with the site worldwide, and around 750 people become members each year. “It’s always a little busier around the time the new movies come out, of course,” she said.

By 1971, heroin and opium use among US troops fighting in Vietnam had reached epidemic proportions, with 42 percent of American servicemen saying they’d tried opioids at least once and around 20 percent claiming some level of addiction, according to the US Department of Defense. Though heroin use by US troops has been little discussed in the context of Taiwan, these and other drugs — produced in part by rogue Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) armies then in Thailand and Myanmar — also spread to US military bases on the island, where soldiers were often stoned or high. American military policeman

Under pressure, President William Lai (賴清德) has enacted his first cabinet reshuffle. Whether it will be enough to staunch the bleeding remains to be seen. Cabinet members in the Executive Yuan almost always end up as sacrificial lambs, especially those appointed early in a president’s term. When presidents are under pressure, the cabinet is reshuffled. This is not unique to any party or president; this is the custom. This is the case in many democracies, especially parliamentary ones. In Taiwan, constitutionally the president presides over the heads of the five branches of government, each of which is confusingly translated as “president”

An attempt to promote friendship between Japan and countries in Africa has transformed into a xenophobic row about migration after inaccurate media reports suggested the scheme would lead to a “flood of immigrants.” The controversy erupted after the Japan International Cooperation Agency, or JICA, said this month it had designated four Japanese cities as “Africa hometowns” for partner countries in Africa: Mozambique, Nigeria, Ghana and Tanzania. The program, announced at the end of an international conference on African development in Yokohama, will involve personnel exchanges and events to foster closer ties between the four regional Japanese cities — Imabari, Kisarazu, Sanjo and

Sept. 1 to Sept. 7 In 1899, Kozaburo Hirai became the first documented Japanese to wed a Taiwanese under colonial rule. The soldier was partly motivated by the government’s policy of assimilating the Taiwanese population through intermarriage. While his friends and family disapproved and even mocked him, the marriage endured. By 1930, when his story appeared in Tales of Virtuous Deeds in Taiwan, Hirai had settled in his wife’s rural Changhua hometown, farming the land and integrating into local society. Similarly, Aiko Fujii, who married into the prominent Wufeng Lin Family (霧峰林家) in 1927, quickly learned Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) and