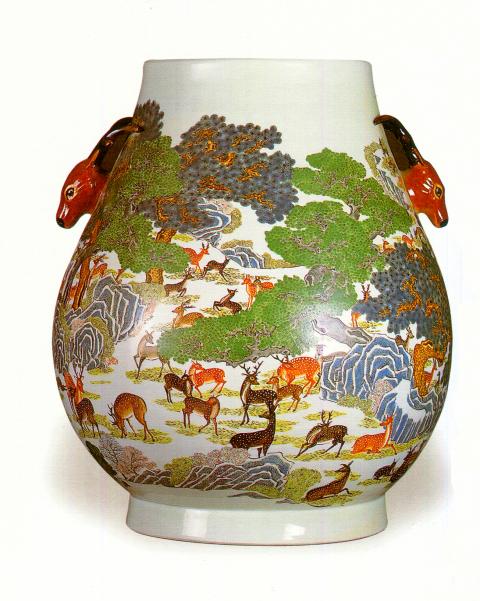

Chen Cheng-ching’s (陳澄清) boss asked him whether he could imitate the decorative motif painted on the National Palace Museum’s Ming 100 Deer Vase (百鹿尊). The Chinese like that one, he said. It symbolizes great wealth. Chen worked on the composition, and his co-workers copied it.

That was back when Chen worked for China Art (市拿陶藝), the first factory established in New Taipei City’s Yingge (鶯歌) to produce imitation ancient Chinese imperial ware ceramics.

“The company was paying me NT$3,000 a month. They sold the vases for NT$50,000 each. They never told me,” Chen tells the Taipei Times, without a hint of anger.

Photo: Paul Cooper, Taipei Times

“The museum’s vase doesn’t actually have 100 deer on it, but mine does. Even so, the museum’s is the better vase,” Chen says.

Chen, 92, sits surrounded by his work: paintings, plates and vases, including one of his 100 deer vases. There are hundreds of painted but unglazed and unfired plates and plaques stored around his apartment in New Taipei City. He has his own electric kiln on the balcony. Amassed notes, together with copies of his self-published book about his life and work, lie scattered on the table.

From 1972 to 1985, Chen was part of an assembly line in the factory, painting decorative motifs for imitation wares. Many of these imitations were sold to Hong Kong dealers for tens of thousands of New Taiwan dollars. These dealers would then sell them to unwitting collectors in the West and Japan as authentic Ming and Qing antiques for 10 times that amount.

Photo courtesy of Chen Cheng-ching

“The Chinese-style vases Western and Japanese buyers were buying during the 1970s and 1980s were all exported from Taiwan,” says Cheng Wen-hung (程文宏), head of the Educational Promotion Department of the New Taipei City Yingge Ceramics Museum.

“It was big money for Yingge. At the time, China Art was making the best work,” Cheng says. “It was the first factory in Taiwan imitating ancient Chinese ceramics.”

The workers, however, were paid low wages.

The market moved on in 1990, when China liberalized its market. People started buying vases from Jingdezhen in China, where official imperial wares for the Chinese court had been produced since the Ming. Imitation wares from there were not only cheaper, they were considered to be more authentic.

BUYER BEWARE

Individually, the imitation wares have an authenticity and intrinsic value of their own. Indeed, the production of imitations of fine pieces from previous dynasties, to replicate antiques favored by the emperors, was common practice in the Qing.

The question of authenticity only arises when the pieces are purported to be, and sold as, something other than they are: genuine ancient Chinese imperial wares, rather than high quality, authentically-produced imitation wares.

China Art would sometimes even sell pieces painted with the reign marks that were historically added to imperial wares made exclusively for the emperors, such as “Made in the Chenghua Reign of the Great Ming Dynasty” (大明成化年製) or “Made in the Qianlong Reign of the Great Qing Dynasty” (大清乾隆年製).

“Vases don’t age,” Cheng says. “If you use the same clay, the same pigments, the same painting techniques, glazes, firing techniques, the question of authenticity often just comes down to guess work.”

Even experts find it difficult to differentiate authentic from fake. “How would you do that?” Cheng asks rhetorically. “From the decor? The decor is really easy to imitate, you just paint it the same way.”

Cheng spoke of one collector who suspected 99 percent of his collection was fake. Even museum curators have to resort to researching the backgrounds of donated Chinese ceramics, he says.

“A vase would be donated by a wealthy family, from their grandfather, who was working in the military during the Qing dynasty, or as an ambassador in China, so they would have to trace the record of the donations,” Cheng says.

RIGHT PLACE, RIGHT TIME

Chen was there right from the beginning, when the factory opened in 1972.

Born in Shaanxi Province, China, in 1924, Chen came to Taiwan with the Republic of China air force, retiring at the age of 46 in 1969. He was familiar with watercolor painting, but had no background in the techniques of painting ceramics. He was introduced to China Art’s founder, Hsu Tse-jan (許自然), by Ho Wei-hsiao (何維孝), an elementary school classmate following a chance encounter in Taipei in 1969.

At China Art, he was trained in the painting techniques used in the Yuan, Ming and Qing dynasties by ceramics painting expert Zheng Ceru (鄭策如), whom Hsu had recruited from Hong Kong in 1969.

During Chen’s stint, he became proficient in the painting techniques. In 1985, he retired, although continued to produce work on commission from former China Art customers. He stopped painting vases in 1988, when he realized that spending all his time creating work for others was little different from what he had left behind at the factory.

Chen then devoted his time to producing a book with examples of his own work, detailing techniques and the correct materials to use. It was published in 2007.

“If I hadn’t written that book ... [h]ow would I pass this valuable information on to later generations?” Chen says.

His painting days are now behind him. His hands shake as he signs copies of his book. The electric kiln on the balcony sits idle. He no longer recalls how to use it.

Yingge Town Artisan is a monthly photographic and historical exploration of the artists and potters linked to New Taipei City’s Yingge Town.

June 23 to June 29 After capturing the walled city of Hsinchu on June 22, 1895, the Japanese hoped to quickly push south and seize control of Taiwan’s entire west coast — but their advance was stalled for more than a month. Not only did local Hakka fighters continue to cause them headaches, resistance forces even attempted to retake the city three times. “We had planned to occupy Anping (Tainan) and Takao (Kaohsiung) as soon as possible, but ever since we took Hsinchu, nearby bandits proclaiming to be ‘righteous people’ (義民) have been destroying train tracks and electrical cables, and gathering in villages

Swooping low over the banks of a Nile River tributary, an aid flight run by retired American military officers released a stream of food-stuffed sacks over a town emptied by fighting in South Sudan, a country wracked by conflict. Last week’s air drop was the latest in a controversial development — private contracting firms led by former US intelligence officers and military veterans delivering aid to some of the world’s deadliest conflict zones, in operations organized with governments that are combatants in the conflicts. The moves are roiling the global aid community, which warns of a more militarized, politicized and profit-seeking trend

The wide-screen spectacle of Formula One gets a gleaming, rip-roaring workout in Joseph Kosinski’s F1, a fine-tuned machine of a movie that, in its most riveting racing scenes, approaches a kind of high-speed splendor. Kosinski, who last endeavored to put moviegoers in the seat of a fighter jet in Top Gun: Maverick, has moved to the open cockpits of Formula One with much the same affection, if not outright need, for speed. A lot of the same team is back. Jerry Bruckheimer produces. Ehren Kruger, a co-writer on Maverick, takes sole credit here. Hans Zimmer, a co-composer previously, supplies the thumping

Dr. Y. Tony Yang, Associate Dean of Health Policy and Population Science at George Washington University, argued last week in a piece for the Taipei Times about former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) leading a student delegation to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) that, “The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world” (“Ma’s Visit, DPP’s Blind Spot,” June 18, page 8). Yang contends that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has a blind spot: “By treating any