Taiwan in Time: May 30 to June 5

After picking up US deputy secretary of state Warren Christopher from Songshan Airport in late December 1978, Leonard Unger found their limousine surrounded by an angry mob.

The truck ahead of them had stopped, and there was no way to escape. The protesters broke the car’s windows and began poking their sticks inside. Finally the truck started moving again, and Unger instructed the driver to take a backroad to his residence in Yangmingshan.

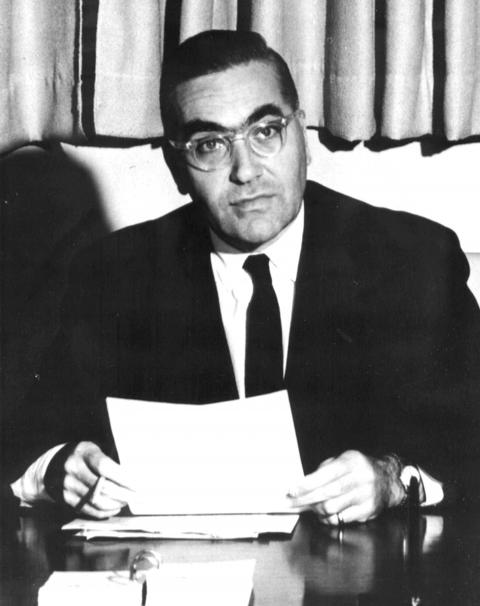

Photo courtesy of US National archives

“We didn’t really know that anything serious had happened to us; we didn’t feel physically hurt at all,” Unger said in a 1989 interview with The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs. “But when my wife saw us, she gasped. Apparently, we were bleeding profusely without knowing it, but only from superficial cuts.”

“I inspected these cars in Taipei four months later,” late American Institute in Taiwan director David Dean wrote in his memoir. “They were total wrecks.”

This was probably not what Unger imagined when he arrived in Taiwan in late May 1974 as US ambassador to Chiang Kai-shek’s (蔣介石) Republic of China government. After a long diplomatic career in Europe and Southeast Asia, Taiwan was to be his last stop before retirement.

Prior to the attack, on the evening of Dec. 15, Unger was pulled aside at an American Chamber of Commerce gala and given the unenviable task of informing president Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國) that the US had decided to severe ties with Taiwan and formally recognize the Beijing-based People’s Republic of China.

Unger had a matter of hours to find Chiang before US president Jimmy Carter made the formal announcement the next morning, finally tracking him down at his residence and convincing his aides to wake him up around 2am.

Unger read to Chiang a letter from Carter, which announced the end of formal relations but guaranteed that “substantive relations” would still continue. All treaties would remain in place except for the Mutual Defense Treaty, which would terminate in one year. The letter also stated that the US would continue to provide “carefully selected defensive arms” to Taiwan — although, per an agreement with China, no transactions were made during the year of 1979.

Historian Henry Tsai (蔡石山) explains why everything was so rushed in his book, Maritime Taiwan: “[National security advisor] Zbigniew Brzezinski was concerned that if Taiwan had too much time to prepare … the KMT authorities might ask the powerful senator Jesse Helms to block Carter’s scheme.”

New York Law School professor Chen Lung-chu (陳隆志) writes in his book, The US-Taiwan-China Relationship in International Law and Policy, that even the US Senate’s Foreign Relations Committee was not informed by Carter until three hours before the announcement.

Unger knew this would happen at some point, as it was the direction which Secretary of State Henry Kissinger had been steering the country toward despite opposition from many Chiang supporters in the US government. But it still came as a surprise.

“I was not sure whether or not I was going to be the last ambassador, but recognized that there was a pretty good chance I would be,” he said a decade later. “In some fashion or other, we would be working out a new relationship with Beijing which would oblige us to reduce our representation in Taipei.”

Taiwan’s international standing had plummeted in the previous decade, and it had been out of the UN since 1971. But the nation was in outrage, seeing it as a betrayal by one of its oldest supporters. Chiang called it a “great setback to human freedom and democratic institutions” and citizens protested outside the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, throwing stones and eggs at the US embassy. An AP article stated that protesters burned the US flag on the street.

Unger was ordered to leave on Dec. 31, 1978, the last day the US recognized Taiwan. But he said he tried to stay as long as possible to try to “help the government of Taiwan adjust to the new situation.”

Facing pressure from Washington, he finally left about two weeks later, and his deputy Bill Brown remained until the Taiwan Relations Act was passed in April, authorizing de facto relations through the American Institute of Taiwan.

A year later, Unger seemed to be feeling positive about Carter’s decision — at least in terms of US concerns. He wrote the following in an article for Foreign Policy magazine:

“Taiwan continues to prosper. The dire predictions of a Soviet-Taiwan alliance, development of nuclear weapons by Taiwan and the proclamation of an independent Republic of Taiwan have not come to pass. And the Chinese have not attempted to take the island by force. None of these calamities appears likely to happen in the foreseeable future.”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

This is the year that the demographic crisis will begin to impact people’s lives. This will create pressures on treatment and hiring of foreigners. Regardless of whatever technological breakthroughs happen, the real value will come from digesting and productively applying existing technologies in new and creative ways. INTRODUCING BASIC SERVICES BREAKDOWNS At some point soon, we will begin to witness a breakdown in basic services. Initially, it will be limited and sporadic, but the frequency and newsworthiness of the incidents will only continue to accelerate dramatically in the coming years. Here in central Taiwan, many basic services are severely understaffed, and

Jan. 5 to Jan. 11 Of the more than 3,000km of sugar railway that once criss-crossed central and southern Taiwan, just 16.1km remain in operation today. By the time Dafydd Fell began photographing the network in earnest in 1994, it was already well past its heyday. The system had been significantly cut back, leaving behind abandoned stations, rusting rolling stock and crumbling facilities. This reduction continued during the five years of his documentation, adding urgency to his task. As passenger services had already ceased by then, Fell had to wait for the sugarcane harvest season each year, which typically ran from

It’s a good thing that 2025 is over. Yes, I fully expect we will look back on the year with nostalgia, once we have experienced this year and 2027. Traditionally at New Years much discourse is devoted to discussing what happened the previous year. Let’s have a look at what didn’t happen. Many bad things did not happen. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) did not attack Taiwan. We didn’t have a massive, destructive earthquake or drought. We didn’t have a major human pandemic. No widespread unemployment or other destructive social events. Nothing serious was done about Taiwan’s swelling birth rate catastrophe.

Words of the Year are not just interesting, they are telling. They are language and attitude barometers that measure what a country sees as important. The trending vocabulary around AI last year reveals a stark divergence in what each society notices and responds to the technological shift. For the Anglosphere it’s fatigue. For China it’s ambition. For Taiwan, it’s pragmatic vigilance. In Taiwan’s annual “representative character” vote, “recall” (罷) took the top spot with over 15,000 votes, followed closely by “scam” (詐). While “recall” speaks to the island’s partisan deadlock — a year defined by legislative recall campaigns and a public exhausted