Taiwan in Time: April 11 to April 17

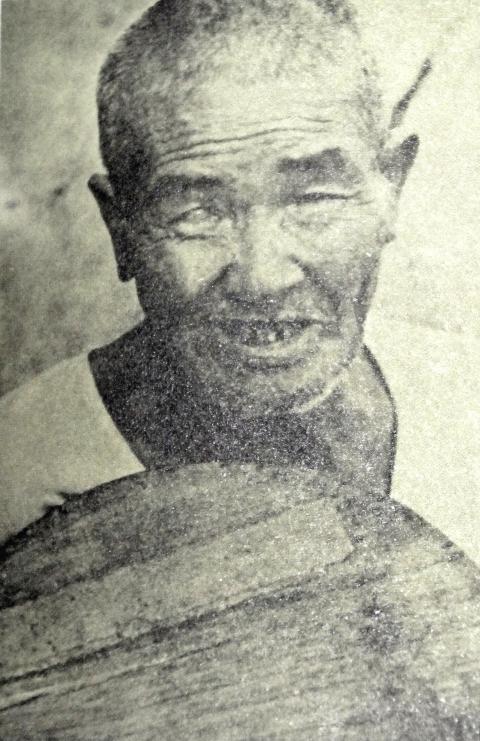

Armed with a moon lute (月琴, yueqin) — a traditional Chinese string instrument — 73-year-old Chen Ta (陳達) sat in a recording studio with Cloud Gate Theater director Lin Hwai-min (林懷民) in 1978. Lin started to explain to Chen the scene he had in mind from the story of Han Chinese immigration from China to Taiwan when Chen interrupted him.

“I know that story,” Chen said. He asked for two cups of rice wine, adjusted his instrument and launched into a detailed, improvised epic. Three hours later, Lin told Chen they had recorded enough material. Chen protested, “I haven’t gotten to the part about Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國) yet!”

Photo: Chen Yan-ting, Taipei Times

He then sang about Chiang, and finished with: “Taiwan became a great place, known by everybody 300 years later.”

That is how Chen, who was illiterate, formed his songs. And he could seemingly go on forever, and was asked at least once to leave the stage because he exceeded his allotted time.

Folk music expert Chien Shang-jen (簡上仁), who recounted the story above in his preface to Chen’s biography The Wandering Bard Chen Da (遊唱詩人陳達) by Hsu Li-sha (徐麗紗), refers to Chen’s songs as “improvised poems based on the time, place and event of that moment.”

Photo: Tsai Tsung-hsien, Taipei Times

His neighbor Chiang Hsiu-ying (江秀英) recalls in the biography that when Chen visited her home, he would first ask her father about the family’s situation and then make up a song on the spot about what he was just told.

“It was always positive and auspicious, and my father would be very happy,” she said. They would then give him some rice or money to buy food.

Born and raised in Hengchun (恆春), Chen learned his craft from his brothers and was considered somewhat of a delinquent for playing music all day and not working in the fields. He honed his skills while working in Taitung (台東) and singing Hengchun-style folk songs with other migrant workers from his hometown.

Photo: Kuo Fang-chi, Taipei Times

Chen began his career as a traveling musician after returning to Hengchun when he was 20 years old, often walking all day from town to town. He was popular among locals — often bringing his audience to tears — but lived in poverty. Handicapped after a stroke at age 29, he never married as a result but is said to have fathered a son with a widow.

Chen did not expect his big break to come in his 60s.

In 1966, Hsu Chang-hui (許常惠) and Shih Wei-liang (史惟亮), both European-educated musicians, decided that Taiwan also needed its own music and set out to document local folk music that was disappearing to Western tunes.

Hsu was saddened by the state of Chen’s life, writing in his journal: “He has no family (no parents, children or relatives), living alone in a house unsuitable for human habitation (if it can be considered a house at all).”

“When he picked up his yueqin and sang with his voice that sounded like cries of grief…I felt that I found it, I found the soul of the Chinese folk music I had been searching for so many years,” Hsu added.

Hsu and Shih then recorded Chen’s songs and released them as records — one of them contained a single long epic on a tragedy involving a father and son who lived in Hengchun. They also actively promoted Chen’s music, attracting much media attention. Chen appeared on television for the first time in a special news program in 1972, where he improvised a song about “two good men who come from Taipei to the south to film a television program.”

Chen became famous — but he still continued to live in poverty, collecting recyclables when he wasn’t playing music. Hsu Li-sha writes that his neighbors considered Chen a talented man but still somewhat looked down on him because he did not have a proper job. This opinion would not change with his fame.

In the late 1970s, Chen was invited to Taipei as a resident performer in a Western music restaurant Scarecrow (稻草人), whose owner wanted to shake things up to save his often empty establishment. Known to never sing the same lyrics twice, he packed the house for two months — but still wore the same tattered clothes, leisurely drinking tea and chewing betel nut as if he were still in Hengchun.

Chen celebrated his 72th birthday in Taipei. It was the first time he had cut a Western-style cake, and he sang a song about it. A few days later, he was the main act at the first annual Folk Artist Music Festival organized by Hsu Chang-hui.

Tired of life in the big city, he eventually returned home, exhausted his earnings and by 1980 he had returned to his old life as a traveling musician, although he would still make trips to perform at schools and other events in Taipei.

On April 11, 1981, Chen was hit by a bus on his way to Hengchun. He died that night.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

June 2 to June 8 Taiwan’s woodcutters believe that if they see even one speck of red in their cooked rice, no matter how small, an accident is going to happen. Peng Chin-tian (彭錦田) swears that this has proven to be true at every stop during his decades-long career in the logging industry. Along with mining, timber harvesting was once considered the most dangerous profession in Taiwan. Not only were mishaps common during all stages of processing, it was difficult to transport the injured to get medical treatment. Many died during the arduous journey. Peng recounts some of his accidents in

“Why does Taiwan identity decline?”a group of researchers lead by University of Nevada political scientist Austin Wang (王宏恩) asked in a recent paper. After all, it is not difficult to explain the rise in Taiwanese identity after the early 1990s. But no model predicted its decline during the 2016-2018 period, they say. After testing various alternative explanations, Wang et al argue that the fall-off in Taiwanese identity during that period is related to voter hedging based on the performance of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Since the DPP is perceived as the guardian of Taiwan identity, when it performs well,

A short walk beneath the dense Amazon canopy, the forest abruptly opens up. Fallen logs are rotting, the trees grow sparser and the temperature rises in places sunlight hits the ground. This is what 24 years of severe drought looks like in the world’s largest rainforest. But this patch of degraded forest, about the size of a soccer field, is a scientific experiment. Launched in 2000 by Brazilian and British scientists, Esecaflor — short for “Forest Drought Study Project” in Portuguese — set out to simulate a future in which the changing climate could deplete the Amazon of rainfall. It is

What does the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) in the Huang Kuo-chang (黃國昌) era stand for? What sets it apart from their allies, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT)? With some shifts in tone and emphasis, the KMT’s stances have not changed significantly since the late 2000s and the era of former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九). The Democratic Progressive Party’s (DPP) current platform formed in the mid-2010s under the guidance of Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文), and current President William Lai (賴清德) campaigned on continuity. Though their ideological stances may be a bit stale, they have the advantage of being broadly understood by the voters.