Vandy Rattana does not want to be known as an artist who produces “stereotypical” images of Cambodia — genocide, the Khmer Rouge or Angkor Wat — he wants to and succeeds in creating art that exudes great pride in being Cambodian.

“I was inspired by this evil,” Rattana says of the genocide, as his film Monologue screens in the background at The Cube Project Space, where his current solo exhibition, Working-Through: Vandy Rattana and His Ditched Footages, is being held.

The artist, who has been living in Taipei for the past three years, has spent much of his time pouring over literature, poetry and philosophical texts, a habit which he picked up when he moved to France in 2009.

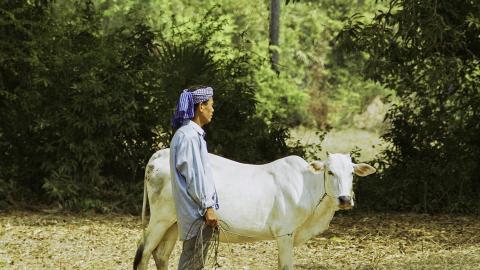

Photo: Dana Ter, Taipei Times

“This poetic point of view helps me to interpret the world better than a logical perspective would, since what happened in Cambodia was illogical,” says Rattana.

This influence has played out in his artwork. Monologue started as a poem he wrote for his sister who he never met. She was murdered by the Khmer Rouge in 1978, two years before he was born and a year before the genocide ended.

Monologue, which centers on her burial place — a mass grave which has since been turned into a rice field — is lyrical and lulling. There are no images of skulls or re-enactments of violence. The narrator (Rattana) tells his sister about the world he lives in, the mango trees that grow in their Phnom Penh house or how it’s human nature to “kill one another” and that we “will never move past that stage.”

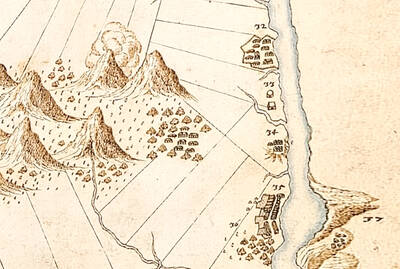

Photo courtesy of Vandy Rattana

The tone is loving and protective, but also matter-of-fact.

Rattana says his motive is not to judge.

“I don’t want to say, ‘he’s wrong, or he’s right.’ I just want to understand,” the artist tells me.

Photo courtesy of Vandy Rattana

HISTORY AS AN INDIVIDUAL RESPONSIBILITY

The journey towards understanding began in 2008. Rattana was living with local farmers in Cambodia’s Kampong Cham Province, photographing rubber plantations for a project when he noticed a couple of very large ponds that were teeming with fish. One day a young villager mentioned to Rattana that they were craters created by bombs dropped by American B-52 bombers during the Vietnam War.

“I felt cheated of not knowing this piece of Cambodian history,” Rattana says.

Photo courtesy of Vandy Rattana

Obsessed with these “bomb ponds,” he traveled around Cambodia searching and photographing them. It was not an easy task since there was not much written by historians in English or Khmer about Operation Menu, the covert American bombing of Cambodia and Laos from 1969 to 1970.

Rattana’s Bomb Ponds series, is, in a sense, revisionist history. It’s hard to tell at first glance what is in the frame. Many of the pictures look like idyllic countryside shots. Throughout the process, people told him to use a bird’s eye perspective to photograph the craters, most of which are 15 meters wide. But he insisted on capturing the point of view as seen by ordinary people who pass by the bomb ponds every day.

“You look at the photograph and think, ‘what a beautiful pond.’ Then you read the caption and you realize that it’s actually a crater and that a bomb created that crater. Your whole perspective changes,” Rattana says.

Though critical of the Cambodian education system, Rattana is glad that it spurred him to find out more information about the past (often via Google and YouTube, he jokes), and by doing so, it felt like he was reclaiming parts of his identity which was taken from him.

“In Cambodia, history learning is an individual responsibility,” he says.

TRAUMA ILLUMINATED BY BEAUTY

Rattana’s photographs do not look like they were taken in 2009. There is a stillness and graininess to them that makes the scenes he captures seem vintage and nostalgic.

The decision to photograph Bomb Ponds with an analog camera was a conscious one, although Rattana now shoots digital, mostly to save time and cost.

“With digital cameras, it’s like you’re eating fast food,” Rattana says.

Everyone may be taking pictures, he says, but are concentrating less on their subject matter. Analog cameras by their very nature, Rattana says, exert greater demands on the photographer, whereas digital cameras have made it easy to lose focus because there is a practically unlimited number of photos that can be shot.

The photographs are raw, grainy and un-embellished for the simple reason that Rattana does not believe in filters, cropping or a lot of editing.

“Other people have the freedom to do that, but it doesn’t seem freeing to me,” he says.

Too much editing would have detracted from the simple message of remembrance and healing. While reading history, Rattana started to question why it was narrated in a depressing way. The photographs in the Bomb Ponds series are not sad per se, but more contemplative, and perhaps a little fatalistic.

Rattana says he wanted to highlight “beauty illuminated by trauma,” and show the various faces of humanity, from the people who dropped the bombs to the historian-photographer (himself) documenting and trying to make sense of it. Rattana does not condemn acts of brutality, though. Rather, he sees it as a sad but integral part of human nature.

“War is just like sex,” he says. “People will keep on doing it until the end of the human race.”

Today, many of the bomb ponds have been filled with new dirt for farmers to grow rice and other crops. The landscape is always changing, and it’s almost as if the photographs are saying, this is what it looks like now, but it might look different in a few years. What history has taught us is that change, good or bad, is inevitable and the onus is on us to remember and move on.

The Nuremberg trials have inspired filmmakers before, from Stanley Kramer’s 1961 drama to the 2000 television miniseries with Alec Baldwin and Brian Cox. But for the latest take, Nuremberg, writer-director James Vanderbilt focuses on a lesser-known figure: The US Army psychiatrist Douglas Kelley, who after the war was assigned to supervise and evaluate captured Nazi leaders to ensure they were fit for trial (and also keep them alive). But his is a name that had been largely forgotten: He wasn’t even a character in the miniseries. Kelley, portrayed in the film by Rami Malek, was an ambitious sort who saw in

Last week gave us the droll little comedy of People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) consul general in Osaka posting a threat on X in response to Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi saying to the Diet that a Chinese attack on Taiwan may be an “existential threat” to Japan. That would allow Japanese Self Defence Forces to respond militarily. The PRC representative then said that if a “filthy neck sticks itself in uninvited, we will cut it off without a moment’s hesitation. Are you prepared for that?” This was widely, and probably deliberately, construed as a threat to behead Takaichi, though it

Among the Nazis who were prosecuted during the Nuremberg trials in 1945 and 1946 was Hitler’s second-in-command, Hermann Goring. Less widely known, though, is the involvement of the US psychiatrist Douglas Kelley, who spent more than 80 hours interviewing and assessing Goring and 21 other Nazi officials prior to the trials. As described in Jack El-Hai’s 2013 book The Nazi and the Psychiatrist, Kelley was charmed by Goring but also haunted by his own conclusion that the Nazis’ atrocities were not specific to that time and place or to those people: they could in fact happen anywhere. He was ultimately

Nov. 17 to Nov. 23 When Kanori Ino surveyed Taipei’s Indigenous settlements in 1896, he found a culture that was fading. Although there was still a “clear line of distinction” between the Ketagalan people and the neighboring Han settlers that had been arriving over the previous 200 years, the former had largely adopted the customs and language of the latter. “Fortunately, some elders still remember their past customs and language. But if we do not hurry and record them now, future researchers will have nothing left but to weep amid the ruins of Indigenous settlements,” he wrote in the Journal of