The multi-billion dollar Ciputra International City complex, in northwest Hanoi, covers 300 hectares of former farmland with mansions, private schools, a clubhouse and fine wine store. Surrounded by thick concrete walls and guarded gates, it is a private enclave of ostentatious wealth — a paradise for the Vietnamese capital’s expatriate and local elite. Inside the gates, wide roads are flanked by luxury cars, palm trees and giant statues of Greek gods.

Across the city, work is under way at Ecopark, a grand, US$8 billion private development being built on the eastern edge of Hanoi. Set to be completed in 2020, it promises secluded luxury with a private university, purpose-built “old town” and 18-hole golf course among the amenities planned. The first phase of the development, named Palm Springs — after the California desert resort city famous for hot springs, golf courses and five-star hotels — has just been completed.

WEALTH GAP

Photo: AFP

Gated communities and vast, privately built and managed “new towns” like these have spread across southeast Asia over the last 20 years as rising levels of inequality have redefined the region’s cities. Vietnam as a whole has seen a dramatic reduction in poverty over the same period — but inequality is growing, and becoming increasingly marked in the country’s expanding urban areas.

“Before, most people were poor. Now it’s different,” says Lam, 40, who grew up on what was then the western fringe of Hanoi in the middle of fields of rice and cherry blossoms, kumquat and peach trees. Today he has a small business selling custom-made picture frames out of a shop-front carved from his house. The fields are long gone, and across the road a thick, high concrete wall separates Lam’s side (an unruly mix of motorbikes, plastic chairs set outside small tea shops, and dangling electrical wires) from the Ciputra complex, gated and guarded by 24-hour private security.

“This side is just ordinary people. Over there, they are rich,” says Mien, 59, who like Lam runs a small business out of her home selling tea, cigarettes and bottles of water and soda. A handful of small plastic stools are scattered on the pavement in front of her one-room house. Between customers she lounges on her bed, a wire frame with no mattress. “Over here we have just enough to live on,” she says.

Photo: AFP

Across Vietnam, the percentage of people living in extreme poverty has fallen from nearly 60 percent to just over 20 percent in the past 20 years. In 2010, the World Bank reclassified it as a “middle-income” country. But as Vietnam has liberalized its economy, so the number of extremely wealthy citizens has skyrocketed. By one estimate, the number of super-rich — those with assets of more than US$30 million — more than tripled in the last 10 years.

And while the wealth gap may be largest between the rural poor and the urban elite, it is most noticeable in the cities where rich and poor live side by side. Bicycles compete with Mercedes and Range Rovers, and walls are going up, dividing high-end property developments from the villages, farms and small one-room houses, doubling up as tea shops and mechanics’ workshops.

“Concerns about inequality will grow as more Vietnamese move to cities and are exposed to the differences between rich and poor,” warned Gabriel Demombynes, a senior World Bank economist, in 2014. Already eight in 10 urban residents said that they worry about disparities in living standards in Vietnam, according to a survey on perceptions of inequality carried out by the bank and the Vietnamese Institute of Labor Science and Social Affairs.

CHASM OF INEQUALITY

Hanoi is an ancient city. In 2010, it celebrated its 1,000th birthday. But now there are plans to gentrify the historic Old Quarter — where the streets still bear the names of the trades that clustered there: Hang Bac (silver), Hang Gai (silk), Hang Bo (baskets) and so on — by pushing thousands of people out of the area by 2020.

In the suburbs, luxury high-rises are going up and enormous master-planned developments are taking over farms and rice fields. Across the city, former collective housing blocks are being demolished and replaced by private apartment complexes. In the city center, well-heeled 20-somethings show off their shiny, vintage Vespas while sipping thick Vietnamese coffee at fashionable cafes.

Lisa Drummond, an urban studies professor at York University in Toronto, has been studying Hanoi for decades. She says a “chasm has begun to open up” between rich and poor in the city, and that developments such as Ciputra and Ecopark reflect — and also perpetuate — these inequalities.

“They remove a group of people from active everyday engagement in the city,” Drummond says. “They take that group of people and allow them to withdraw from the city, behind walls; to have their own private facilities in an economically homogeneous space — because, of course, money buys entry to that space, so only those with money can be there.”

Beyond Ciputra’s walls, villas painted shades of beige are set amid lush private gardens — with price-tags of as much as US$4,250 a month to rent (25 times the minimum wage). A world unto itself, the complex is a land of Greek revival architecture, tennis courts and amenities including a beauty salon and a post office. The UN’s International School moved there in 2004, followed by two other private schools, and a private kindergarten. Under construction still are a mega-shopping mall and a private hospital.

Built in the early 2000s to house up to 50,000 people, Ciputra was Hanoi’s first “integrated new town development,” and the first overseas project of the Ciputra Group, an Indonesian conglomerate named after its billionaire founder that specializes in large-scale property developments and private townships. Designed so that residents rarely need to leave — or interact with the world around them — the company says the Hanoi complex offers “the very best of living, business, shopping, leisure and entertainment in one premier location.” Today it is one of a growing number of gated communities and large-scale private townships in and around the city.

Danielle Labb, professor of urban planning at the University of Montreal, has been following the explosion of master-planned “new urban areas” in Hanoi for years. She estimates there are about 35 of these projects already completed in Hanoi, with as many as 200 more at different stages in the pipeline.

Not all of these developments — where housing, infrastructure and other services are built at the same time — are physically gated, and most are not as large as Ciputra or Ecopark, says Labb? But the projects all share a principal target market: the wealthiest residents in the city.

“The reality is that these projects, the housing and the living environments that are produced, are basically out of reach to the majority of the population,” Labb says, despite there being “an enormous demand for urban housing in Vietnam which is not being met.”

ENCLAVES OF CLEAN AIR

Real-estate developers and investors around the world have ploughed billions into gated communities and increasingly ambitious master-planned developments. In western India, Lavasa is an audacious US$30 billion project to build the country’s first entirely private city. From Punta del Este in Uruguay to Bangkok, Thailand, elite enclaves are being carved out of cities on every continent.

But while security concerns and a fear of urban crime are typically among the motives driving the elite behind walls in cities in South America and sub-Saharan Africa, in Hanoi developments are increasingly being marketed as exclusive enclaves of convenience and clean air, away from the air pollution and traffic congestion of the city.

On Hanoi’s worst days, thick smog blankets the city. Street hawkers across the city sell multicolored, fabric surgical-style masks, now ubiquitous on its congested roads. Millions of motorbikes and a growing number of cars kick up dust and spew smoke into the air, honking horns and revving engines. Crossing the street can be a dangerous move, particularly for children and the elderly, and fear is spreading about the health impact of the city’s increasingly polluted air.

According to Drummond: “There’s a lot of discussion now about how the air in Hanoi is very bad, how the city is very polluted, that it’s full of garbage. It’s beginning to acquire a bit of a sense of dangerousness, of toxicity.”

But, she says, by creating spaces where “the wealthy can remove themselves from the city,” elite urban developments marketed for their superior environmental qualities “perpetuate the sense of the central city as a space that is to be avoided, and perpetuate the gap between those who have the wealth to make that move and those who don’t.”

On a late weekday morning, traffic is in full swing outside Ciputra’s gates. But inside the development — marketed as a “ peaceful oasis among the hustle and bustle of Hanoi “ — it is calm and quiet. Street hawkers are not allowed inside, and the only sound of life is that of children playing in the yard of one of the complex’s elite private schools.

Across the city, on the eastern edge of Hanoi, Ecopark similarly advertises a “perfect harmony of humans and nature,” boasting of “various open areas where you and your family can go for a walk or simply sit under the shade of a tree for a picnic, and enjoy nature at its best.”

Developed by Viet Hung Urban Development and Investment, a joint venture of several Vietnamese property companies, Ecopark is a mammoth 500-hectare master-planned development. Set to be fully developed in 2020, Ecopark is opening in phases, with its first community — Palm Springs — already complete and home to 1,500 apartments, 500 villas and 150 shophouses.

Eventually, this new “township” will have a number of connected but separate areas including a “resort-style community” offering a “sanctuary of only the highest standards and services” with swimming pools, tennis courts and “chic outlet shopping”. The private British University Vietnam is also building a US$70 million campus for up to 7,000 full-time students.

On a weekday afternoon, a recently opened neighborhood in the development is quiet, with more guards patrolling the streets than pedestrians. Beyond the swimming pool and landscaped greens, a shop — without any customers — has a floor lamp in the window on sale for US$1,700, or more than 10 times the minimum monthly salary for a worker in Vietnam.

In a small cafe just inside the complex’s gates, a trio of men who work for one of the development’s contractors, managing a team of construction workers, say they would move to Ecopark if they could afford it. “Of course it is nice to live here,” says Hai, 39. “[It is a] great environment. People are nice here, [there are] good services. We work here and we hope that one day we will earn enough money to buy a house here.”

But for most Vietnamese people, living in Ecopark is far out of reach, and the project’s development has been marred by repeated protests from local communities who have lost their rice fields and farmland to its expansion.

In 2006, construction was temporarily suspended amid protests by local communities who were losing their land to the project. Protests erupted again in 2009 and 2012. In April 2012, police descended on local villagers armed with stones and molotov cocktails, firing teargas into the crowds, in one of the country’s most violent land disputes in recent memory. Several protesters were arrested and journalists documenting the evictions were reportedly beaten by the police.

Across Vietnam, communities have protested against low levels of compensation given for land that has been taken for large-scale industrial and real-estate developments. “There have been protests, everywhere in the country, in the last few years,” Labb says.

“They know how much their land is worth,” she adds, and those who lose it are “left with very few opportunities afterwards. They don’t get jobs in these projects. These new urban zones are not planned to generate very much employment besides domestic services, working as maids, which is not what most villagers are hoping for themselves or their children.”

— Travel for this article was supported by funding from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting

May 26 to June 1 When the Qing Dynasty first took control over many parts of Taiwan in 1684, it roughly continued the Kingdom of Tungning’s administrative borders (see below), setting up one prefecture and three counties. The actual area of control covered today’s Chiayi, Tainan and Kaohsiung. The administrative center was in Taiwan Prefecture, in today’s Tainan. But as Han settlement expanded and due to rebellions and other international incidents, the administrative units became more complex. By the time Taiwan became a province of the Qing in 1887, there were three prefectures, eleven counties, three subprefectures and one directly-administered prefecture, with

President William Lai (賴清德) yesterday delivered an address marking the first anniversary of his presidency. In the speech, Lai affirmed Taiwan’s global role in technology, trade and security. He announced economic and national security initiatives, and emphasized democratic values and cross-party cooperation. The following is the full text of his speech: Yesterday, outside of Beida Elementary School in New Taipei City’s Sanxia District (三峽), there was a major traffic accident that, sadly, claimed several lives and resulted in multiple injuries. The Executive Yuan immediately formed a task force, and last night I personally visited the victims in hospital. Central government agencies and the

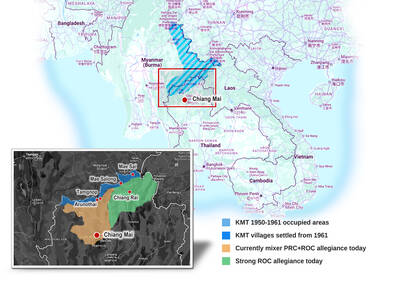

Among Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) villages, a certain rivalry exists between Arunothai, the largest of these villages, and Mae Salong, which is currently the most prosperous. Historically, the rivalry stems from a split in KMT military factions in the early 1960s, which divided command and opium territories after Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) cut off open support in 1961 due to international pressure (see part two, “The KMT opium lords of the Golden Triangle,” on May 20). But today this rivalry manifests as a different kind of split, with Arunothai leading a pro-China faction and Mae Salong staunchly aligned to Taiwan.

As with most of northern Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) settlements, the village of Arunothai was only given a Thai name once the Thai government began in the 1970s to assert control over the border region and initiate a decades-long process of political integration. The village’s original name, bestowed by its Yunnanese founders when they first settled the valley in the late 1960s, was a Chinese name, Dagudi (大谷地), which literally translates as “a place for threshing rice.” At that time, these village founders did not know how permanent their settlement would be. Most of Arunothai’s first generation were soldiers