Death of a Bachelor, Panic! at the Disco, DCD2/Fueled by Ramen

The new album by Panic! at the Disco is called Death of a Bachelor, but its core concern isn’t death so much as the afterlife. Brendon Urie, the band’s emphatic mind and mouthpiece, wants to know what happens in the wake of a bacchanal, when the wildest urges thrash only in the rear view. “Welcome to the end of eras,” he sings on Emperor’s New Clothes, sounding rueful as well as relieved: Farewell to all that, but not without a highlight reel.

If Urie, 28, sounds like someone adjusting to new circumstances, there may be good reason for that. He’s a couple of years into married life, which imbues songs about being lonely while in love, like House of Memories, with an intriguing frisson.

Meanwhile, another union in Urie’s life has officially been torn asunder. After a series of personnel shake-ups, his band, formed in 2004 by childhood friends in Las Vegas, recently scaled all the way back to a solo act. (As an amusingly blunt credit in the CD booklet puts it, “Panic! at the Disco Is: Brendon Urie.”) Not that the album, which was largely produced by Jake Sinclair, sounds any less Day-Glo spectacular than the group’s past dispatches.

Panic! at the Disco has always favored a style both steroidal and slick, and Urie isn’t out to reinvent it here. So if the album’s title is meant to evoke Death of a Ladies’ Man, the 1977 album by Leonard Cohen, the analogy never scratches past the surface. A larger touchstone, especially on the title track, is Frank Sinatra — although Urie doesn’t have the vocal subtlety or the empathy to flesh out his emulation.

What he does have, now as ever, is panache: He’s a firecracker of a frontman, unafraid of strident commitment to a garish conceit. On Victorious, he evokes both the flamboyant swagger of Queen and the mechanized gleam of Daft Punk. On L.A. Devotee, he proudly sings of “drinking white wine in the blushing light.”

Urie has no problem reframing circusesque debauchery, a lyrical trademark, in terms of past indiscretion. It happens on Don’t Threaten Me With a Good Time, which hijacks a twangy guitar riff from the B-52s, and Hallelujah, which mercifully has nothing to do with Cohen’s best-known song. (Instead, it’s a power-pop gloss on a gospel idea.)

It’s in these flickers of conflicted Dionysian feeling that the album has a sense of purpose, beyond what Urie describes at one point as “the symphony buzzing in my head.” To that end, it’s fascinating to consider his premise on Crazy=Genius, a relationship battle royale with a thundering tom-tom beat. “She said you’re just like Mike Love/But you’ll never be Brian Wilson,” he reports, and it’s easy to imagine just how much that line would have stung.

— Nate Chinen, NY Times News Service

The Bell, Ches Smith, ECM

Ches Smith’s The Bell is an excitingly slippery album, both conceptually and physically, in the playing. It appears to be delicate chamber music for percussion, viola and piano. Then it slides into something else: trenchantly rhythmic, improvised music, alive with smeary, interactive connections among the three players: the drummer Smith, the violist Mat Maneri and the pianist Craig Taborn.

Those slides are gradual. Some songs clearly have landmarks, in agreed-upon melodic themes and tonal centers. But the line between written and unwritten grows blurry, since much of The Bell is airy and slow, using the spaces around notes, both in terms of time and pitch. Smith, when he’s not playing drum patterns, scrapes his cymbals with the fat end of his drumstick, dislodging a spray of different tones. Taborn plays with an even grace, choosing his phrases and harmonies meticulously; and Maneri, as usual, makes notes from his instrument warp and palpitate, as if they were pouring from an old ballad singer.

Smith is a drummer who leans toward jazz: He plays regularly in bands led by Tim Berne, Marc Ribot, Mary Halvorson, Darius Jones and Matt Mitchell. But he has post-punk and experimental composed music in his background. He can be abrupt and severe, but not here. This is a pretty delicate hour of listening.

It’s difficult to remember The Bell as a single entity after you’re finished with it, because it always seems to be moving somewhere different. Yet many of these songs do have a common procedure: They’re about two-thirds one thing and one-third another. In Isn’t It Over, I’ll See You on the Dark Side of the Earth and I Think, a diffuse area leads into a mesmerizing groove or a repeated melodic theme; For Days essentially reverses that pattern. In either case, the group can disorient you, scrambling your expectations about tension, development and release.

— Ben Ratliff, NY Times News Service

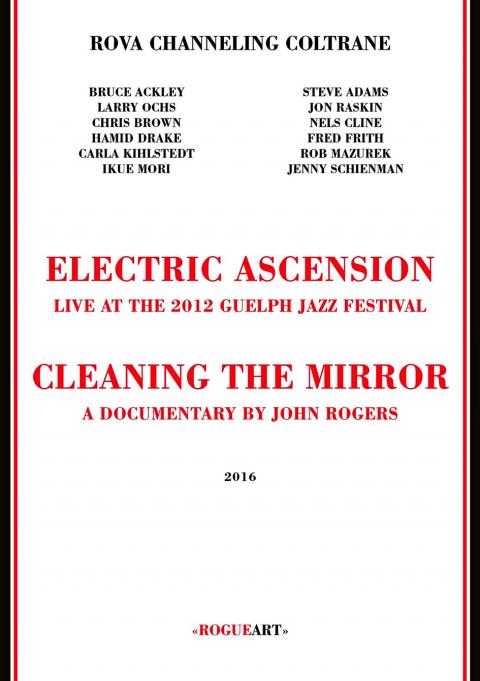

Rova Channeling Coltrane, Rova Saxophone Quartet, Rogue Art

Transience and permanence each play a role in any landmark recording of free jazz. This is especially true of Ascension, the large-canvas album made by the saxophonist John Coltrane in 1965. An experiment in form and scale, it was never performed in concert, even though that would seem to be its ideal manifestation.

The members of Rova Saxophone Quartet, an intrepid ensemble formed in the San Francisco Bay Area more than 35 years ago, took this into consideration when they conceived Electric Ascension, a repertory tribute group stocked with texture-mad improvisers like the guitarist Nels Cline. The expanded assemblage has toured in Europe and North America, and a vital album — Electric Ascension, credited to Rova::Orkestrova — was released on Atavistic in 2005.

Rova Channeling Coltrane similarly chronicles a live performance, highlighting the ephemeral qualities of the music. But because this new release contains not only an album but also a concert film and a behind-the-scenes documentary, it offers a more multilayered experience. (A surround-sound version of the album, on an enclosed Blu-ray disc, includes the option to tinker with the mix, focusing on a particular musician’s output within the collective squall.)

The music, from a 2012 concert in Guelph, Ontario, is at once ecstatic, enigmatic and volatile, often suggesting a flow of complex systems. But there are signposts, starting with Coltrane’s thematic overture, and there’s a method, overseen by two of Rova’s founding members, the saxophonists Jon Raskin and Larry Ochs.

The roster on Rova Channeling Coltrane includes Cline, Ikue Mori on electronics, Rob Mazurek on cornet and Hamid Drake on drums. Their interplay is striking: Each transaction feels contingent on its immediate context — what happened a moment ago, and what’s in the moment ahead.

Over a roughly 70-minute span, the music keeps realigning among smaller subgroups of players. One poetic stretch, emerging out of a cacophony, involves just Jenny Scheinman’s mournful violin and Cline’s quietly ringing chords; another has Scheinman and Carla Kihlstedt embroidering a dialogue on violin, against a percussive rustle. These smallish moments underscore the power of the full ensemble whenever it heaves into gear.

Electric Ascension, featuring Cline and others, appears on Sunday night at Le Poisson Rouge as part of the NYC Winter Jazzfest. Rova will also be at the Stone from Tuesday through Jan. 24, working with partners including the saxophonist and composer John Zorn.

— Nate Chinen, NY Times News Service

Cheng Ching-hsiang (鄭青祥) turned a small triangle of concrete jammed between two old shops into a cool little bar called 9dimension. In front of the shop, a steampunk-like structure was welded by himself to serve as a booth where he prepares cocktails. “Yancheng used to be just old people,” he says, “but now young people are coming and creating the New Yancheng.” Around the corner, Yu Hsiu-jao (饒毓琇), opened Tiny Cafe. True to its name, it is the size of a cupboard and serves cold-brewed coffee. “Small shops are so special and have personality,” she says, “people come to Yancheng to find such treasures.” She

Late last month Philippines Foreign Affairs Secretary Theresa Lazaro told the Philippine Senate that the nation has sufficient funds to evacuate the nearly 170,000 Filipino residents in Taiwan, 84 percent of whom are migrant workers, in the event of war. Agencies have been exploring evacuation scenarios since early this year, she said. She also observed that since the Philippines has only limited ships, the government is consulting security agencies for alternatives. Filipinos are a distant third in overall migrant worker population. Indonesia has over 248,000 workers, followed by roughly 240,000 Vietnamese. It should be noted that there are another 170,000

In July of 1995, a group of local DJs began posting an event flyer around Taipei. It was cheaply photocopied and nearly all in English, with a hand-drawn map on the back and, on the front, a big red hand print alongside one prominent line of text, “Finally… THE PARTY.” The map led to a remote floodplain in Taipei County (now New Taipei City) just across the Tamsui River from Taipei. The organizers got permission from no one. They just drove up in a blue Taiwanese pickup truck, set up a generator, two speakers, two turntables and a mixer. They

Hannah Liao (廖宸萱) recalls the harassment she experienced on dating apps, an experience that left her frightened and disgusted. “I’ve tried some voice-based dating apps,” the 30-year-old says. “Right away, some guys would say things like, ‘Wanna talk dirty?’ or ‘Wanna suck my d**k?’” she says. Liao’s story is not unique. Ministry of Health and Welfare statistics show a more than 50 percent rise in sexual assault cases related to online encounters over the past five years. In 2023 alone, women comprised 7,698 of the 9,413 reported victims. Faced with a dating landscape that can feel more predatory than promising, many in