Seoul office worker Park Sun-min constantly checks his smartphone — trawling for updates on an insect apocalypse, ghost soldiers haunting the inter-Korean border, and a supermarket worker’s struggle to form a trade union.

Along with millions of other South Koreans, Park is, by his own admission, irrevocably hooked on the vast network of varied Internet-based comic strips — or “webtoons” — available through his mobile. “I read four to five a day and more than 30 a week ... I sometimes see them at work and keep reading them on holiday — even overseas,” the 30-year-old said.

The genre is a growing cultural force in South Korea, supported by an ultra-fast Internet and smartphone-crazy populace, and fueled by a small army of young, creative, tech-savvy graphic artists. Most webtoon serials are published on major Internet portals free of charge once or twice a week. They cover pretty much every genre, from romantic comedies to horror, via historical epics and crime.

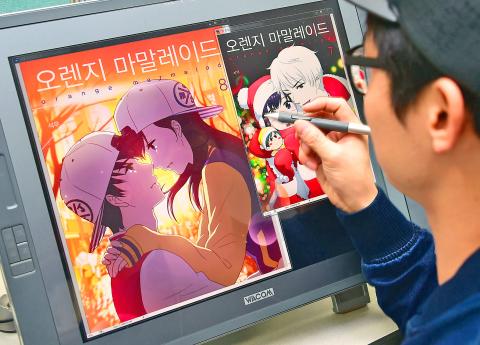

Photo: AFP/Jung Yeon-je

Their popularity has drawn the attention of the wider entertainment industry, and top rated webtoons have been successfully adapted into TV dramas, films, online games — even musicals.

According to Digieco, a Seoul-based technology think tank, the market for webtoons, and their “derivatives,” is currently valued at around US$368 million and is expected to more than double by 2018.

STEEP EARNING CURVE

A recent example of the sort of stellar trajectory a webtoon can take was provided by Misaeng (or Incomplete Life) — a highly-acclaimed series about a young part-time worker trying to survive South Korea’s cutthroat corporate culture.

The twice-weekly comic built up an Internet readership of one million, and the series was collated in a book version that sold two million copies.

A TV drama spin-off was a major hit last year, and the final accolade came when the government named a new piece of legislation to help part-time workers after the webtoon’s main character.

“I think this is a distinctive genre ... and the market is exploding at a mind-blowing pace,” said Cha Jung-Yoon, a spokesman for Naver — Seoul’s top Internet portal. South Korea had a traditional comics industry which all but collapsed during the 1997-98 Asian financial crisis that drove many publishers into bankruptcy. But the Internet opened a new door. Naver launched a dedicated webtoon section in 2005, commissioning three artists whose work attracted 10,000 views a day.

The section now boasts more than 220 commissioned artists and 7.5 million daily views, Cha said, adding that 75 percent of readers are aged 20 or older.

‘A WHOLE NEW GENRE’

Most webtoons are created digitally, often in long-strip format for scroll-down viewing on computers or smartphones.

Many contain moving, flashing or 3D images as well as sound effects and background music. Some even make the smartphone vibrate when readers scroll to a certain scene.

“Webtoons are not simply scanned versions of print comics. It’s a whole new, different genre tailored for the Internet age,” said Kim Suk, senior researcher at state-run Korea Creative Content Agency.

“The introduction of smartphones in 2009 was a watershed moment for webtoons ... it really fueled their growth,” Kim said. More than 80 percent of the country’s 51 million population own smartphones, allowing fans to read webtoons anywhere, and they have become particularly popular with commuters.

Seok-Woo became a full time webtoon artist after a series he devised — a psychological thriller about school bullying — won a 2007 competition to publish a regular series on Naver.

The 32-year-old, who writes under his given name, grew up in a family that moved a lot when he was a teenager, leaving him feeling friendless and isolated.

“Many artists blend their own life experiences into the story and that often resonates well with readers,” he told AFP.

Action heroes are relatively rare — often the most popular webtoons are those dealing with issues like poverty, cyber bullying, suicide, youth unemployment and domestic violence.

WEBTOON A-LISTERS

With fan bases growing, dozens of webtoon creators earn six-figure US dollar incomes, made up of fees from Internet portals and advertisers, as well as licensing contracts for TV shows, films and other adaptations.

A handful of A-listers appear on TV talk shows, attend mass signing events with fans and give motivational speeches to cartooning hopefuls.

But the competition is intense.

Hundreds post their webtoons online each week, hoping to attract a big enough fan base to push them into the big time — a contract with one of the major Internet portals.

“It’s actually quite nerve-racking because readers rate each episode, with the number of clicks and readers’ feedback shown right in front of your face each week,” Seok-Woo said. His webtoon — a teenage romance called Orange Marmalade — became a hit and was adapted for television.

“It’s a bit surreal how the webtoon has become a next big thing so quickly,” he said after returning from a book-signing tour in Indonesia, where a translated version of Orange Marmalade has garnered a whole new set of fans.

The most popular South Korean webtoons are now being offered in Internet and mobile platforms in China and Japan. And, after a barrage of requests from foreign fans, Naver recently created a global service offering hit webtoons in English, Chinese, Thai and Indonesian.

Recently the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and its Mini-Me partner in the legislature, the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), have been arguing that construction of chip fabs in the US by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電) is little more than stripping Taiwan of its assets. For example, KMT Legislative Caucus First Deputy Secretary-General Lin Pei-hsiang (林沛祥) in January said that “This is not ‘reciprocal cooperation’ ... but a substantial hollowing out of our country.” Similarly, former TPP Chair Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) contended it constitutes “selling Taiwan out to the United States.” The two pro-China parties are proposing a bill that

Institutions signalling a fresh beginning and new spirit often adopt new slogans, symbols and marketing materials, and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) is no exception. Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文), soon after taking office as KMT chair, released a new slogan that plays on the party’s acronym: “Kind Mindfulness Team.” The party recently released a graphic prominently featuring the red, white and blue of the flag with a Chinese slogan “establishing peace, blessings and fortune marching forth” (締造和平,幸福前行). One part of the graphic also features two hands in blue and white grasping olive branches in a stylized shape of Taiwan. Bonus points for

March 9 to March 15 “This land produced no horses,” Qing Dynasty envoy Yu Yung-ho (郁永河) observed when he visited Taiwan in 1697. He didn’t mean that there were no horses at all; it was just difficult to transport them across the sea and raise them in the hot and humid climate. “Although 10,000 soldiers were stationed here, the camps had fewer than 1,000 horses,” Yu added. Starting from the Dutch in the 1600s, each foreign regime brought horses to Taiwan. But they remained rare animals, typically only owned by the government or

“M yeolgong jajangmyeon (anti-communism zhajiangmian, 滅共炸醬麵), let’s all shout together — myeolgong!” a chef at a Chinese restaurant in Dongtan, located about 35km south of Seoul, South Korea, calls out before serving a bowl of Korean-style zhajiangmian —black bean noodles. Diners repeat the phrase before tucking in. This political-themed restaurant, named Myeolgong Banjeom (滅共飯館, “anti-communism restaurant”), is operated by a single person and does not take reservations; therefore long queues form regularly outside, and most customers appear sympathetic to its political theme. Photos of conservative public figures hang on the walls, alongside political slogans and poems written in Chinese characters; South