Taiwan in Time: Nov. 9 to Nov. 15

It was supposed to be a routine air force bombing drill near Hangzhou, China, but Li Xianbin (李顯斌) had other plans.

Although the weather wasn’t ideal, the 28-year-old pilot of an Il-28 Soviet jet bomber had already decided that the morning of Nov. 11, 1965 would be a once-in-a-lifetime chance to execute his plan.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Without warning, Li turned his plane southward. His crewmates, Lian Baosheng (廉保生) and Li Caiwang (李才旺), realized what was going on and tried to stop their pilot, but it was too late.

They were headed toward Taiwan.

Although the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) rulers of Taiwan offered a reward for any Chinese soldiers who defected (as did China for Taiwan’s defectors), Li Xianbin insisted later that he didn’t do it for the money, but that he couldn’t take the “inhumane practices” of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) any more.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

It was later indicated that Li had clashed with his superiors over military promotion issues and was also upset with the CCP over the death of several of his relatives during a famine.

Between 1960 and 1989, about a dozen Chinese fighter planes successfully made the cross-strait “defection to freedom” (投奔自由), as the KMT called it in those days, while a lesser number of Taiwanese ones flew the other way in what their communist rivals called a “revolutionary return” (起義歸來). Each side ceased their reward policy as tensions eased in 1988.

Li flew the plane dangerously close to the water to avoid radar detection until he approached the military airport in Taoyuan. Due to the weather and unfamiliarity with the terrain, he couldn’t land properly and damaged the nose and front wheels of the plane.

The official account states that Lian died in the crash, but both Li Caiwang and Li Xianbin later claimed that Lian committed suicide because he didn’t want to come to Taiwan. Li Caiwang received an award of about NT$1.4 million, while Li Xianbin took home double that amount.

Since their arrival took place right before KMT cofounder Sun Yat-sen’s (孫逸仙) birthday celebration, the media touted them as the “best birthday present” and both took part in the festivities.

Both ended up serving in Taiwan’s air force, but neither were allowed to fly again, reportedly due to the KMT’s fear that they would bring military secrets back to China.

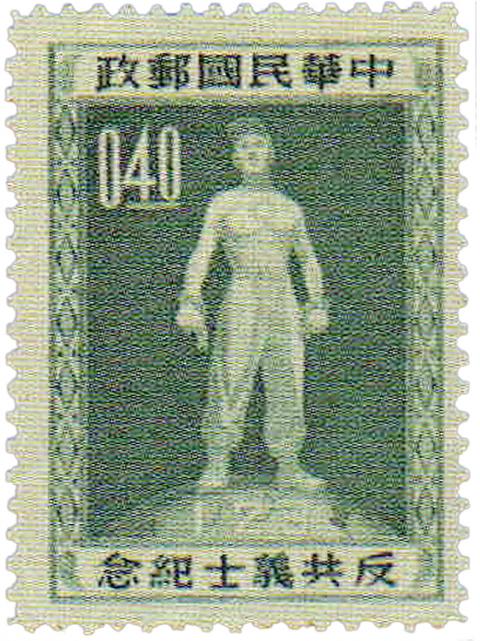

The KMT pronounced all three as anti-communist martyrs (反共義士), and portrayed them as heroes. They participated in various anti-communist propaganda activities and even made it into elementary school textbooks as freedom-seeking patriots. After the communists learned of Lian’s suicide years later, they made him a revolutionary martyr (革命烈士).

The Ministry of National Defense planned to utilize these defectors to persuade the communists to surrender, to serve as propaganda to the public and for possible espionage.

Li Caiwang retired in 1977 and emigrated to the US. In 1983, he returned to China, claiming to authorities that he was forced by Li Xianbin to defect and re-declared his loyalty to the CCP, denouncing his anti-communist martyr designation.

Li Xianbin followed a similar path, emigrating to Canada in 1990. On Dec. 16, 1991, he and his wife went to China to visit his ailing mother. He had had reportedly received repeated guarantees from China’s embassy that the 20-year statute of limitations had expired and he would not be arrested for his prior actions.

The visit went well, but as Li Xianbin was about to return to Canada, he was arrested and sentenced to 15 years in prison as a “defector and traitor.” Alas, a provision allows any crime punishable by death or life in prison to be prosecuted past the 20-year statute of limitations with the permission of the Supreme People’s Procuratorate, China’s top prosecuting body.

Li Xianbin was paroled in 2002 because of poor health, and died of cancer in Shanghai about six months later, in the very land that he had risked everything to escape from.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

In the American west, “it is said, water flows upwards towards money,” wrote Marc Reisner in one of the most compelling books on public policy ever written, Cadillac Desert. As Americans failed to overcome the West’s water scarcity with hard work and private capital, the Federal government came to the rescue. As Reisner describes: “the American West quietly became the first and most durable example of the modern welfare state.” In Taiwan, the money toward which water flows upwards is the high tech industry, particularly the chip powerhouse Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電). Typically articles on TSMC’s water demand