Reginald Kell, Busch Quartet, BRAHMS, Clarinet Quintet, Testament SBT 1001

David Shifrin, Emerson Quartet, BRAHMS, Clarinet Quintet, DG-E 4596412

Martin Frost, BRAHMS, Clarinet Quintet, BIS BIS2063

Boris Rener, Ludwig Quartet, BRAHMS, Clarinet Quintet, 8554601

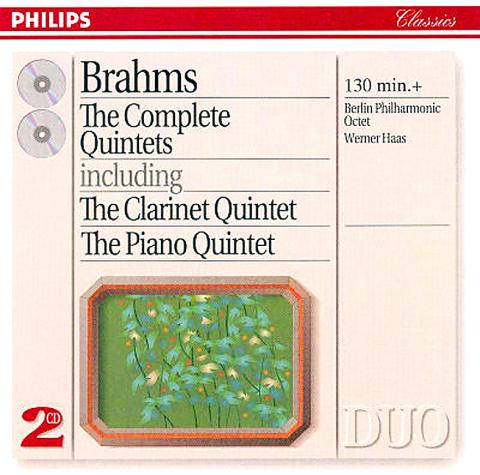

Berlin Philharmonic Octet, BRAHMS, The Complete Quintets, Philips Duo CDA-1647

Brahms’s Clarinet Quintet is one of chamber music’s greatest masterpieces. It’s ruminative, endlessly inventive, autumnal but also funny, and altogether a delight through and through.

According to www.PrestoClassical.co.uk there are an astonishing 95 versions currently available. Imagine my surprise, then, when in answer to asking which recording they preferred, two super-knowledgeable (and super-perceptive) friends, one in Italy, the other in the US, both independently opted for a version from 1937.

The term “chamber music” originally meant just that — music to be performed, not in a concert-hall, but in a room, or “chamber.” But it quickly took on a character of its own, the feeling that it’s a private, introspective exercise, the composer communing with himself, rather than penning something that’s intended for public display.

Another development was that the string quartet, a work for two violins, a viola and a cello, came to be regarded as the central chamber music form. The balance between the instruments seemed ideal, and first Haydn, then Mozart (influenced by Haydn), and then Beethoven (influenced in at least one instance by Mozart), all produced a whole sequence of masterpieces in the genre.

Quintets — very often a string quartet with one extra instrument added — were always rarer. They could be either string quintets (with either a second viola or a second cello added), or they could introduce a different kind of instrument, such as a piano or, as in one of Mozart’s most sublime works, a clarinet.

Johannes Brahms differed from the norm, however. Despite being an out-and-out classicist, he held back from composing string quartets, just as he initially held back from composing symphonies. Perhaps his very classicism made him aware of how illustrious his predecessors had been. Could he really equal Haydn and Mozart, let alone Beethoven? Either way, he claimed to have destroyed 20 string quartets before finally issuing his first two at the age of 40. And he only ever published three, none of them great works.

With quintets, however, it was a different matter. There are four in the Brahms canon, and two of them are undoubted triumphs. The Piano Quintet never really satisfied Brahms or his audiences. It was first conceived as a string quintet, but Brahms tore it up — a fact that hasn’t prevented one modern enthusiast from trying to reconstruct (and perform) it, and another from re-writing it for full orchestra. One way or another, it has never seemed quite right. His first string quintet, too, is less than brilliant.

But the Second String Quintet is one of the most beautiful things he ever wrote (as someone reputedly shouted out during its first rehearsal). And then there’s the Clarinet Quintet, the subject of today’s investigation.

Anyone attempting to write a clarinet quintet is going to be in the shadow of Mozart’s masterpiece. It’s confidently distinctive and richly melodic at one and the same time, profoundly aware of the clarinet’s character, and structurally original (it has two trios, for example, in the third movement instead of the usual one).

It seems to me that Brahms solved the problem of the pre-eminence of his predecessor, not by trying to evade it, but by embracing it. Echoes, or near-echoes, of the Mozart work proliferate, but at the same time Brahms’s work is highly original, with a dazzling third movement that’s quite unforgettable.

The version recommended by my friends is by clarinetist Reginald Kell. He was born in the UK in 1906 and moved to the US in 1948 where he taught the famous jazz clarinetist Benny Goodman.

Kell actually recorded the Brahms Clarinet Quintet twice, first with the Busch Quartet, then with the Fine Arts Quartet. The first of these is the one recommended by my friends, though the friend based in Italy added that the sound quality could be better. The one based in Vermont added that a professional clarinetist he knows also recommended a more modern recording, implying that he too knew the sound quality of the vintage Kell version wouldn’t please everybody. This modern version is from the Emerson Quartet, with clarinetist David Shifrin, recorded in 2010. Coupled with Mozart’s clarinet quintet, it looks an excellent choice.

Much praised, too, is a version by the Swedish clarinetist Martin Frost. This comes with Brahms’s Clarinet Trio and five Brahms songs transcribed for clarinet and piano. Naxos has a version from Boris Rener and the Ludwig Quartet, based in France, described as “excellent” by the BBC Music Magazine. And I’ve long enjoyed a two-CD budget item from Philips that conveniently includes all Brahms’s four quintets. The clarinetist is Herbert Stahr, accompanied by members of the Berlin Philharmonic Octet.

And then of course there’s YouTube, and as usual surprise is the name of the game here. No sooner had I begun a search for Brahms’s Clarinet Quintet than I caught sight of an upload (by one Motti Adler) of the slow movement, played by the Jerusalem Quartet and Sharon Kam, accompanied by sea paintings by the American naturalist painter Winslow Homer (1836-1910). For some reason, I found this totally ravishing.

Why should paintings of people in boats, and walking along the shore, combined with Brahms at his most lyrical, prove so mesmerizing? Did the paintings throw light on the music, or vice-versa? They certainly both came from the same era. But I suspect something was happening to me at a deep psychological level. Anyway, try it and see what you think.

May 26 to June 1 When the Qing Dynasty first took control over many parts of Taiwan in 1684, it roughly continued the Kingdom of Tungning’s administrative borders (see below), setting up one prefecture and three counties. The actual area of control covered today’s Chiayi, Tainan and Kaohsiung. The administrative center was in Taiwan Prefecture, in today’s Tainan. But as Han settlement expanded and due to rebellions and other international incidents, the administrative units became more complex. By the time Taiwan became a province of the Qing in 1887, there were three prefectures, eleven counties, three subprefectures and one directly-administered prefecture, with

Taiwan Power Co (Taipower, 台電) and the New Taipei City Government in May last year agreed to allow the activation of a spent fuel storage facility for the Jinshan Nuclear Power Plant in Shihmen District (石門). The deal ended eleven years of legal wrangling. According to the Taipower announcement, the city government engaged in repeated delays, failing to approve water and soil conservation plans. Taipower said at the time that plans for another dry storage facility for the Guosheng Nuclear Power Plant in New Taipei City’s Wanli District (萬里) remained stuck in legal limbo. Later that year an agreement was reached

What does the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) in the Huang Kuo-chang (黃國昌) era stand for? What sets it apart from their allies, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT)? With some shifts in tone and emphasis, the KMT’s stances have not changed significantly since the late 2000s and the era of former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九). The Democratic Progressive Party’s (DPP) current platform formed in the mid-2010s under the guidance of Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文), and current President William Lai (賴清德) campaigned on continuity. Though their ideological stances may be a bit stale, they have the advantage of being broadly understood by the voters.

In a high-rise office building in Taipei’s government district, the primary agency for maintaining links to Thailand’s 108 Yunnan villages — which are home to a population of around 200,000 descendants of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) armies stranded in Thailand following the Chinese Civil War — is the Overseas Community Affairs Council (OCAC). Established in China in 1926, the OCAC was born of a mandate to support Chinese education, culture and economic development in far flung Chinese diaspora communities, which, especially in southeast Asia, had underwritten the military insurgencies against the Qing Dynasty that led to the founding of