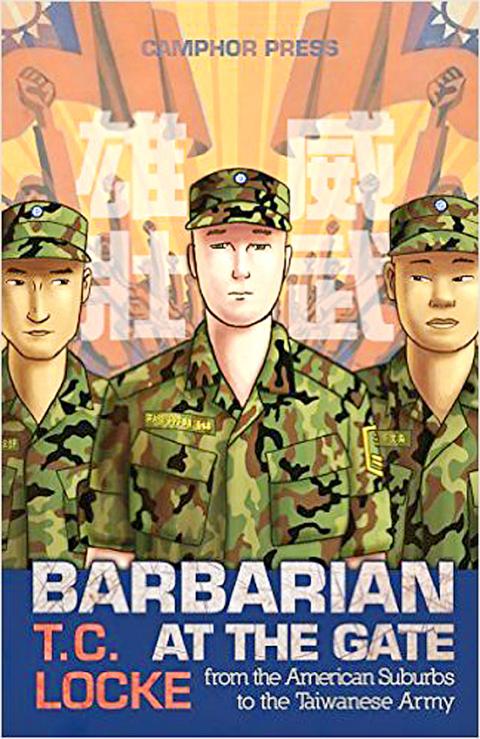

A barbarian at the gate was a foreigner or other outsider at an ancient walled city’s gates, threatening to enter. Attila outside Rome comes to mind, but the phrase has become proverbial and can refer to any imminent threat. The ancient Chinese saw all foreigners as barbarians, and TC Locke, a left-handed man born on Christmas Day in the US, has said he sees himself in the phrase. Most unusually, in 1994 he renounced his American nationality and took Taiwanese citizenship. Subsequently he had to do military service, at that time two years, and this book is an account of that experience. Whether he was a threat to anyone, however, is a matter of opinion, making the book’s title, Barbarian at the Gate, for the most part ironic.

The book was originally published in Chinese in 2003, but this English version, seemingly not a literal translation, dates from last year. Locke opted for the then new Camphor Press after feeling his Chinese book hadn’t been promoted very energetically by its big-time publisher.

Army life

He did most of his service in Miaoli County, but there’s plenty about Taipei too, where he retreated when he had any leave. But the army is the army wherever it’s encountered, and many of its bizarre traditions — such as valuing length of service just as much as, and on occasion more than, rank — would be remarkable anywhere.

There are several muted gay references early on in the book. Locke says he felt himself a cultural orphan in his youth due to the “stifling presence of bigotry and homophobia.” He later writes that he spent his adolescence “waiting for feelings of attraction to the opposite sex.” In Taiwan, studying Chinese in Taichung, he reports he hung out with a group of gays, and found them “normal human beings like anyone else.” It consequently comes as a surprise that he doesn’t describe encountering any gays in the Taiwanese army, virtually an all-male society after all. Surely, over two years, there must have been some such incidents. The lack of anything of the kind in the narrative constitutes a minor disappointment, but perhaps any inclination to gay behavior was rigorously suppressed by all and sundry in that strange world. All we read is that a squad having to strip naked in 20 seconds might in civilian life have “made for a barely believable scenario for the start of a porn video.”

The main point about this book isn’t that Locke tries to be as like his Taiwanese fellow soldiers as possible but that he is almost entirely like them. He endures bullies like everyone else, standing up to one or two but for the most part taking their treatment lying down. He’s happy when what to the reader seem like insignificant promotions come his way, doesn’t report a group playing the strictly forbidden game of poker, manages to befriend the normally feared Military Police and so on. His greatest fear appears to be being singled out for being white, and indeed one or two senior officers do double-takes when first catching sight of him, but it never goes further than that. His hopes of landing an army job where he can use his English proficiency, however, come to nothing.

One incident stays in the memory. Locke was, and presumably still is, a talented trumpet player. One day an officer arrives and asks if any of the recruits has any musical ability. Five come forward, and it transpires that all claim skill playing the trumpet. The reality is, however, that Locke is the only one with any real talent, but the officer appears reluctant to select him on the grounds that he wants the band in question to display a certain uniformity (presumably of physical appearance). So the officer arranges a lot-drawing between Locke and one of the incompetents. Unfortunately Locke finds there is only one disc in the bag he has to choose from, and of course it’s the loser’s. The officer thus avoids having to choose him while saving face in the process.

Humiliation

Scenes involving the deliberate humiliation of recruits, such a sergeant leaping onto a refectory table and kicking away trays of uneaten food, are par for the course. Such techniques, designed to turn recent civilians into subservient military personnel, probably characterize armies everywhere, though the Taiwanese military have — or had in Locke’s day — a reputation for severity. The attraction of this book, though, is that such figures, though appearing as ogres when first encountered, later become individuals, some of whom Locke later meets on a more equal basis.

This is not to say that TC Locke (nowadays also known as TC Lin) ever approaches being the professional soldier. Like many of his fellow conscripts he considers the option of signing on for a longer stint, with much better pay and a choice of roles in which to serve, but like the majority decides against it.

So he learns army songs, helps a distressed farmer slaughter a herd of pigs with foot-and-mouth disease (exuding what looks like a mixture of saliva and blood from mouth and hoof), sets up a karaoke room for officers and counts the days left before his discharge. In an Epilogue, he re-visits his former camp only to find it abandoned and overgrown, the scenes of his victories and humiliations now a mass of weeds.

Locke is generally an observant and thoughtful narrator. Though he reads science-fiction novels by Isaac Asimov and sometimes listens to classical music, he’s in no way aloof. It could be argued that his desire to fit in overrides all else, but this doesn’t seem to be quite the case either. He’s intelligent without being an outsider, astute without being a radical, and generally modest and self-effacing. This makes for a reader-friendly book that many English-speakers, especially expatriates living in Taiwan, won’t find it difficult to enjoy.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the