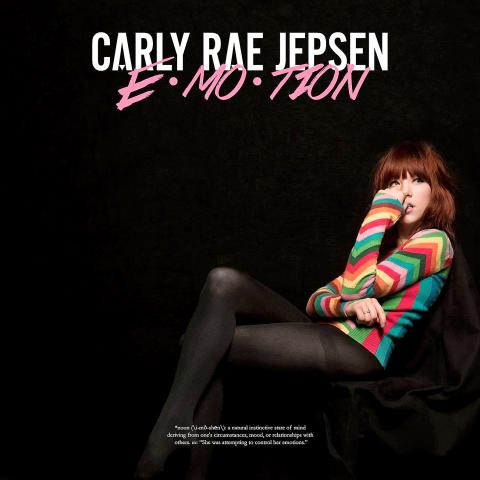

Emotion , Carly Rae Jepsen, Schoolboy/Interscope

The year is 2015, yet surly clouds of shame still hover over those fortunate enough to have had one spectacular pop hit. How many streaming services must die before these blessed artists understand that their one calling-card hit is a wonder not to escape, but to embrace?

Carly Rae Jepsen, of Call Me Maybe mania — a fever that gripped the nation in 2012 — spends much of her ecstatic, slightly frizzy second major-label album, Emotion (Schoolboy/Interscope), trying to establish her bona fides in thinking-person’s pop, a fool’s task.

Emotion is full of pure cotton candy — delicious, distractingly sweet and filling, with a mildly suspicious aftertaste. Jepsen turns to the synthetic, plastic part of 1980s pop for inspiration, channeling in particular the chaste teen female dreamboats of the time: Debbie Gibson, Tiffany, a pre-erotic-awakening Janet Jackson.

Jepsen has a sweet voice, though not a commanding one. It makes sense that her big hit was a halfhearted flirt ending in “maybe” and that the new album’s obvious attempt to rebottle lightning, I Really Like You, repeats the “really” six times each go-round, as if all Jepsen can do is pile on the like, never aware that love may be just around the corner.

To achieve this revisionist fantasy, she worked with some Swedes (Mattman & Robin) but more important, the power team of Ariel Rechtshaid and Devonte Hynes, who over the last couple of years have reinvented big-top 1980s synth-pop as backdoor cool-kid music.

They both worked on the sinister All That, one of the album’s highlights: slow-smolder ‘80s R&B full of disembodied, percussive guitar licks. Jepsen is at her breathiest here: “I wanna play this for you all the time/ I wanna play this for you when you’re feeling used and tired.”

The synthesizers gleam and sparkle but never swell to a satisfying thickness. As mercenary and cocksure as this songwriting is, there’s a reluctance that holds it — or her — back. This is the case throughout this album, full of excellent songs that seem to give up about two-thirds of the way through. They run up to the cliff’s edge and don’t jump.

Jepsen, once thrust so abruptly into the spotlight, seems eager to be cloaked by sounds more authoritative than she is. Warm Blood, produced by Rostam Batmanglij of Vampire Weekend, is sickly and viscous, and there are John Hughes movie drums on When I Needed You. If Jepsen has modern templates, they’re the upstart clients Hynes and Rechtshaid have fuel-injected with major-league structure: Haim, Solange, Sky Ferreira.

In fact, Emotion is something like a photonegative of Ferreira’s outstanding 2013 album, Night Time, My Time. Many of the inputs are the same, the tempos are familiar, the callbacks go to the same years. But Ferreira is a glamorous terror, scathing in her pulpy takedowns, be they of herself or of others.

Jepsen, on the other hand, prefers not to get scraped. Emotion is more mature than her 2012 major-label debut, Kiss, but only somewhat. And even when she’s talking grown-folks business, like on L.A. Hallucinations — “I remember being naked/We were young freaks just fresh to L.A.” — it’s in a voice that never sweats, only twinkles.

Maybe Jepsen’s choices merely reinforce the new centrist pop model of ‘80s sleekness (Taylor Swift, the Weeknd). It’s more likely, though, that she hoped to put some distance between her and her old pair of goody two shoes.

That’s a fine choice, of course. And on this album, often an effective one. But why fall under the spell of someone else’s cool when you can luxuriate in the stink of your own.

— JON CARAMANICA, NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

Radiate, Liberty Ellman, Pi Recordings

The guitarist Liberty Ellman has a knack for streamlining gnarly complexities into clean, appealing curvature. That’s one reason he has been an ideal lieutenant to maverick multireedist and composer Henry Threadgill, whose flagship band, Zooid, is unimaginable without Ellman’s nimble etchings on acoustic guitar.

But Ellman, 44, has his own vision as a composer-bandleader. So it’s a little curious that Radiate, his first album in nearly a decade, begins with a conspicuous nod to Threadgill. The album’s opening track, Supercell, finds Jose Davila, another member of Zooid, puffing a syncopated line on tuba before the onset of a jagged, patently Threadgillian theme.

Maybe it’s not quite accurate to call this curtain-raiser an act of misdirection, but the bulk of Radiate shimmies free from the burden of influence. Ellman, working from his own script, generates an impressive range of ideas for his dynamic sextet, which (along with Davila) includes trumpeter Jonathan Finlayson, alto saxophonist Steve Lehman, bassist Stephan Crump and drummer Damion Reid.

Ellman has a tone and touch that can evoke midcentury jazz-guitar styles, though his limber solos also draw from classical music and from the dialect of his peers. He phrases his output with an implicit sense of breath; on “Furthermore,” which unfolds in a fever-dream rubato, his lines evoke the cadence of oratory.

Almost every track seems to have an animating idea, a reason for being, though they aren’t made explicit. On Vibrograph it might be the spectral composition techniques that Lehman has made his trademark, working with some of these same musicians. And on Enigmatic Runner, it’s the use of electronics, as both a textural choice and an intervening force. Ellman, who dabbles in distortion and pedal effects elsewhere on the album, pushes himself further here, producing a track that’s startling in its surface disruptions. But it pulls you forward, and it has a flow.

— NATE CHINEN, NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

High, Royal Headache, What’s Your Rupture?

The first album by the Australian band Royal Headache was better than good — rushed, trebly, volatile garage-punk, with a singer who took his job unusually seriously.

His name was Shogun, and he sounded close to the surface. He sang a lot about heartsickness and a little about head-sickness. Excitingly, he seemed to be in the process of finding his voice — he could settle in a vague midrange, or push it up high, heaving out bright lines full of chest and grit, getting at Sam Cooke via early Rod Stewart, or a second-tier British Invasion singer.

High comes four years later: a long time for a band this scrappy. Royal Headache had some success with the first record — not too much, but just enough to create internal problems. Shogun has given frank interviews about not being cut out for touring life, and before the new record came out he said that the band would be finished after its latest tour, although now he seems to be saying otherwise.

The standard narrative is that a band’s second record reflects experience, wisdom or moderation, and High has a bit of that in a larger and more managed sound. There are more songs here about love and desire, but there are also some with a new stripe: outrage, possibly self-directed. Two songs are better than anything the band has done yet. Another World might, possibly, describe the mixed feelings of an aspiring singer getting what he wants. And Garbage begins with the sounds of glass in a trash compactor before leveling intimate accusations of moral failure. “You’re as low as they come,” Shogun concludes early in the song, arranging those words into a proper melody. “You’re not punk; you’re just scum.” His startling, frustrated roar, toward the end, at 3:11, sounds real.

— BEN RATLIFF, NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,