Yayoi Kusama may be the world’s most popular artist. She is an 86-year-old woman who lives by choice in a mental institution in Japan and is known for paintings of polka dots. Last year, her exhibitions drew more visitors than any other living artist, with more than two million attending her various touring exhibitions in Latin America and Asia. Her works fetched over US$44 million at auction last year, the most by any living female artist. And she has a strong and almost completely user-generated presence online, with over 173,000 images tagged with the #YayoiKusama hashtag on Instagram (more than #JeffKoons with 138,000 tags but well shy of #AndyWarhol with 448,000).

In many ways, Kusama’s success is unprecedented, and not only because she is a female artist.

GLOBAL REACH OF ART

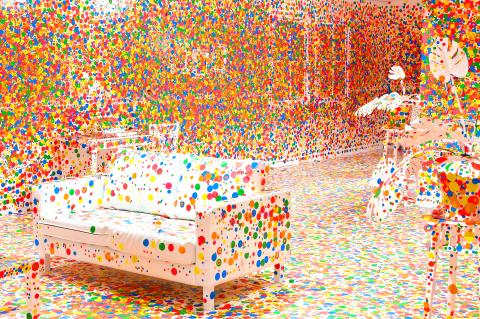

Photo courtesy of National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts in Taichung

The Art Newspaper recently dubbed her the “poster girl for the globalization of contemporary art,” an epithet which drives home the point that perhaps for the first time in history, a living visual artist can now enjoy stardom in cities as far flung as London, Mexico City and Seoul and mount exhibitions that tour the world like a rock band.

Taiwan has not been left out of this roadshow. Kusama’s touring exhibition for Asia, A Dream I Dreamed, is now on display at the National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts in Taichung and runs to Aug. 30.

The exhibition, which includes around 120 paintings, sculptures and installations, was organized by the curators at the Daegu Art Museum in Korea, where it was first mounted in 2013. It has since traveled to Seoul, Shanghai and earlier this year to the Kaohsiung Fine Arts Museum, where it attracted over 170,000 visitors from February to May. The Taipei Museum of Fine Arts had also put in a bid to host the exhibition, and when the bid failed it caused some consternation in the local media. After Taiwan, the exhibition will continue on to New Delhi.

Photo courtesy of National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts in Taichung

What is the source of Kusama’s massive and now global appeal?

For half a century, Kusama has painted polka dots and other simple patterns — most notably overlapping loops that she calls “infinity nets” — on canvases, naked human bodies, home interiors, sculptures of common natural objects like melons and flowers, and giant inflatable blobs, which themselves act as polka dots when placed in a landscape.

Born in Japan, Kusama claims to have experienced hallucinations of dots as a child and began inserting them into sketches from her early teens. Frustrated with her philandering father and Japan’s restrictive education system, she moved to New York in the late 1950s, where she fell into the budding Pop Art movement and became a social radical. While exhibiting alongside the likes of Andy Warhol and Claus Oldenburg in the 1960s and early 1970s, she staged protests and happenings, including a march on Wall Street (featuring nude dancers covered in polka dots) meant as a protest against the capitalists funding the military aggression in Vietnam.

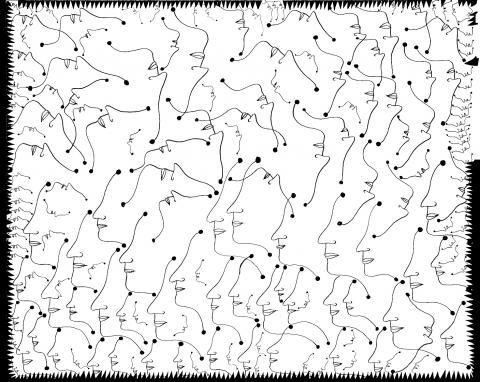

Photo courtesy of National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts in Taichung

Kusama also advocated wildly for free love and other liberal forms of sexuality. This included publishing a racy magazine called Kusama’s Orgy, hosting a homosexual wedding and writing an open letter to then president Richard Nixon, promising to have sex with him if he’d stop the Veitnam War. But despite her outward sexual exuberance, she was averse to physical sex, and her only known relationship is a platonic affair with the surrealist sculptor, Joseph Cornell, who was 26 years her senior.

In 1973, Kusama moved back to Japan and opened an art gallery, which failed, as had her other artistic endeavors up to that time. In 1977, she checked herself into a mental institution and has lived there ever since, though she continues to commute to her studio, where she paints furiously, producing several hundred paintings a year, even now at the age of 86.

Kusama’s life makes for a fascinating story. It is not fully told in the current exhibition, A Dream I Dreamed, which instead focuses on the artist’s recent fame as a global pop phenomenon, presenting her as a sort of Hello Kitty of contemporary art. Aside from a bed covered in stuffed fabric penises, Repetitive Vision — Phallus Boat (2000), which is easy to overlook, the show is G-rated presentation of the artist’s recent oeuvre, with almost all the works produced in the last 10 years, since Kusama reached the age of 75.

A Dream I Dreamed was no doubt conceived with a big box office in mind, and makes the most of presenting Kusama’s fancifully patterned world to a public groomed on the art from Picasso to Andy Warhol.

One encounters work that is easy to identify as “art” — not least of all because about half the exhibition consists of paintings, which combine various Modernist styles from early 20th century abstraction to minimalism and Pop Art. Kusama paints in a naive almost childlike hand, presenting vividly colored patterned fields or else scribbles of suns, faces, eyes, jags, circles and wavy lines. As a group, they are a formidable pastiche of painters like Joan Miro, Henri Matisse, post-cubist Picasso and even Jean Michel-Basquiat — but without ever attaining the refinement, the nuance and the painterly brilliance of those artists.

But Kusama’s larger project is not really about style per se, but instead seeks to transform the world into a world of polka dots, which is also to say a world of pattern and prettiness and love and happiness. There is a femininity to it, and a naivete — it is almost girly, though on a grand scale. Her ability to insert a female sensibility into the world of serious, male-dominated art — movements like abstraction, minimalism and Pop Art — will perhaps be remembered as her greatest historical achievement.

Kusama certainly counts as a modernist, painting, as Kandinsky would have put it, out of “inner necessity,” or as she puts it, out of “obsession.” But unlike her male counterparts, her work is playful and self-consciously decorative — never serious, austere or intellectual. One could perhaps set her at the opposite pole from the color field painter Mark Rothko, who claimed a sense of “tragedy, ecstasy and doom” in his pursuit of abstract beauty.

‘INFINITY MIRRORED ROOM’

One of the most popular displays in the current exhibition is Infinity Mirrored Room — Brilliance of Souls (2014) — you will need to queue up to enter, and the wait can be up to two hours. This installation is a rectangular chamber the size of a small bedroom, with mirrors covering the interior walls, floor and ceiling. More than a thousand colored balls of light dangle at varying heights, and their reflections seem to extend to infinity, giving the impression of standing in the midst of a prettified cosmos.

This is also the way Kusama imagines death, and related sentiments bubble up in the painting series My Eternal Soul (which she began at the age of 80), a poem titled “I want to live forever, but…” and numerous other works.

In her autobiography, Kusama writes, “by covering my entire body with polka dots, and then covering the background with polka dots as well, I find self-obliteration.” This notion of death is a peaceful one, a process of simply fading into the background of a dotty universe.

But she is not there yet. Kusama also recently stated, “I want to paint 1,000 or 2,000 paintings. I want to keep painting even after I die.” For now, she is merely dissolving into the creative act.

The unexpected collapse of the recall campaigns is being viewed through many lenses, most of them skewed and self-absorbed. The international media unsurprisingly focuses on what they perceive as the message that Taiwanese voters were sending in the failure of the mass recall, especially to China, the US and to friendly Western nations. This made some sense prior to early last month. One of the main arguments used by recall campaigners for recalling Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers was that they were too pro-China, and by extension not to be trusted with defending the nation. Also by extension, that argument could be

Aug. 4 to Aug. 10 When Coca-Cola finally pushed its way into Taiwan’s market in 1968, it allegedly vowed to wipe out its major domestic rival Hey Song within five years. But Hey Song, which began as a manual operation in a family cow shed in 1925, had proven its resilience, surviving numerous setbacks — including the loss of autonomy and nearly all its assets due to the Japanese colonial government’s wartime economic policy. By the 1960s, Hey Song had risen to the top of Taiwan’s beverage industry. This success was driven not only by president Chang Wen-chi’s

Last week, on the heels of the recall election that turned out so badly for Taiwan, came the news that US President Donald Trump had blocked the transit of President William Lai (賴清德) through the US on his way to Latin America. A few days later the international media reported that in June a scheduled visit by Minister of National Defense Wellington Koo (顧立雄) for high level meetings was canceled by the US after China’s President Xi Jinping (習近平) asked Trump to curb US engagement with Taiwan during a June phone call. The cancellation of Lai’s transit was a gaudy

The centuries-old fiery Chinese spirit baijiu (白酒), long associated with business dinners, is being reshaped to appeal to younger generations as its makers adapt to changing times. Mostly distilled from sorghum, the clear but pungent liquor contains as much as 60 percent alcohol. It’s the usual choice for toasts of gan bei (乾杯), the Chinese expression for bottoms up, and raucous drinking games. “If you like to drink spirits and you’ve never had baijiu, it’s kind of like eating noodles but you’ve never had spaghetti,” said Jim Boyce, a Canadian writer and wine expert who founded World Baijiu Day a decade