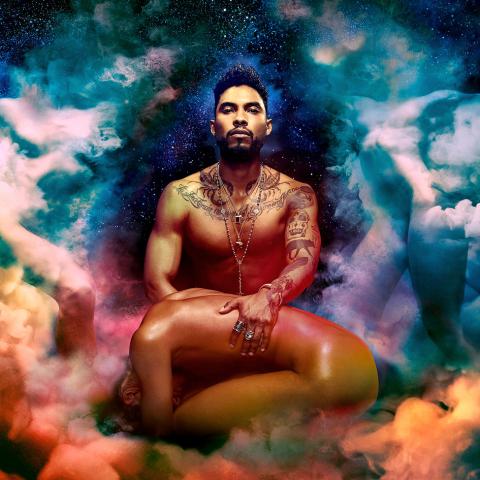

Wildheart, Miguel, Bystorm Entertainment/RCA

Carnality, musical ambition and flickers of conscience have swirled through the songs of Miguel — the Los Angeles songwriter Miguel Jontel Pimentel — since his 2008 Mischief EP. Kaleidoscope Dream, his second album and commercial breakthrough in 2012, put romance and desire in the foreground for R&B hits like Adorn, which hinted at Marvin Gaye’s Sexual Healing and won a Grammy for best R&B song. Yet like Gaye, Miguel was never just a come-on artist, and popularity has emboldened him.

On Wildheart, his third album, Miguel follows his clashing impulses further: toward love and death, raunch and exaltation, doubt and confidence, salvation and damnation, cynicism and hope. He also defies the synthetic, robotic sound of current R&B, cranking up electric guitars and exposing his voice, taking chances while building exquisite productions. Wildheart deserves a place alongside the latest albums by D’Angelo and Kendrick Lamar; it’s both rooted and daring, delving into the personal as it reaches for broad statements. It also invites comparisons to Prince, not only for Miguel’s ingenious, multifarious rock and soul hybrids but also for his determination to address dualities and contradictions.

The core of the album is What’s Normal Anyways? a rock ballad that starts with a lone electric guitar and ponders Miguel’s mixed heritage — a Mexican-American father and an African-American mother — on the way to a larger confession: “I never feel like I belong/I want to feel like I belong somewhere.” It’s a chorus for everyone growing up and seeking an identity. But where’s the place to belong?

On Wildheart, it’s California, beautiful and corrupt, which is Miguel’s birthplace and the recurring locale for the songs. Waves, a rocker paced by a busy cowbell, celebrates the beach and urges a woman to “body surf on me.” A descending, grunge-toned guitar line betrays the ambivalence of Hollywood Dreams, which moves from hopes of stardom to the routine of exploitation. Leaves, another post-grunge rocker, observes “the leaves don’t change here” before mourning a breakup in “sweet California, bitter California.”

At times, romance offers a refuge. In Face the Sun, Miguel affirms, “I belong to you” as Lenny Kravitz’s guitar climbs toward an arena-scale solo. In Coffee, a plush ballad with nervous electronic undercurrents, “Sweet dreams turn into coffee in the morning” and the romance is so strong that “two lost angels discover salvation.”

But on this album, lust also leads to sleazier temptations. In Flesh, Miguel’s falsetto sketches shifting power games over a slow-motion groove and distorted guitar. And in The Valley, Miguel calls for sex “like we’re filming in the Valley” — that’s the San Fernando Valley, a hub for pornography — amid synthesizers that pulse and slide with the bleak indifference of Nine Inch Nails. Deal, which rides a strutting funk beat amid spooky electronics, zeros in on a different kind of debasement: corporate cash in government.

Miguel doesn’t resolve the tensions and contradictions, much less smooth them over. He doesn’t always try to play the good guy or the heartthrob, either. The music, meanwhile, places sinuous tunes, pushy guitars and lush vocals against uneasy backdrops — seductive, but never without second thoughts.

— Jon Pareles, NY Times News Service

Ego Death, The Internet, Odd Future

Right from the beginning, Ego Death, the third album by the Internet, radiates confident lust. On the opening song, Get Away, the singer Syd tha Kyd talks about what it’s like to be an object of desire when you’re somewhere between the modest past and the success of an uncharted tomorrow. From the outside, she’s living “a life of luxury, models in my money trees,” but the reality is more relatable: “I’m still driving ‘round in my old whip/Still living at home got/issues with my old chick.”

As she feels her way to seduction even in these humble circumstances, the music behind her is aquatically soothing, communicating a sort of erotic safety. That’s the tenor of much of this impressive album, the best thus far by this group — Syd tha Kyd and producer Matt Martians — that’s been honing its come-ons for years at the fringes of the Odd Future carnival.

The Internet makes soul music that’s redolent of the mid- to late 1990s, just when hip-hop’s influence on R&B was beginning to congeal into what later became known, somewhat derisively, as neo-soul. Think the chill ecstasy of Groove Theory, or the pulsing swing of Davina, or even the dreamier production by the Soulquarians. That means there’s convincing thump at work here, but not so much as to overwhelm the lustrous keyboards, the nuzzling bass, the way several of the songs unfurl like blooming roses. (Special nod to the multi-instrumentalist Steve Lacy, who plays on and produces several songs here, peaking with the slithering bass on Special Affair.)

Syd is a plain talker and a sensuous singer, and she oozes through these tracks with casual swagger. In places she gives caress a break, as on Under Control, where she borrows phrasings from Pharrell Williams on his early work with N.E.R.D., or Penthouse Cloud, a stoned-sounding rock song with political text — “Did you see the news last night? They shot another one down” — that Syd sings almost dreamily, above the madness.

But mostly, her vocals are hot breath on a cool neck. “Cigarettes and sex on your breath I guess/It’s cool, I’m the same the way/We kiss,” she sings, through a smoothing digital effect, on For the World. On Palace, she’s offering her partner a dream night, or a dream life: “A couple games if you wanna play/Wings on my back if you wanna fly away.”

Though it shouldn’t merit notice in a nation that’s finally made marriage equality a matter of law, the fact that Syd is a woman singing to other women still feels striking and meaningful. Not because it’s rare — for every instance of blithe same-sex tourism like Katy Perry’s I Kissed a Girl, there’s been a Melissa Etheridge, a Tegan and Sara, a Mary Lambert singing loud and proud. But there’s a matter-of-factness to Syd’s approach that feels like the sound of the new commonplace.

— Jon Caramanica, NY Times News Service

June 2 to June 8 Taiwan’s woodcutters believe that if they see even one speck of red in their cooked rice, no matter how small, an accident is going to happen. Peng Chin-tian (彭錦田) swears that this has proven to be true at every stop during his decades-long career in the logging industry. Along with mining, timber harvesting was once considered the most dangerous profession in Taiwan. Not only were mishaps common during all stages of processing, it was difficult to transport the injured to get medical treatment. Many died during the arduous journey. Peng recounts some of his accidents in

“Why does Taiwan identity decline?”a group of researchers lead by University of Nevada political scientist Austin Wang (王宏恩) asked in a recent paper. After all, it is not difficult to explain the rise in Taiwanese identity after the early 1990s. But no model predicted its decline during the 2016-2018 period, they say. After testing various alternative explanations, Wang et al argue that the fall-off in Taiwanese identity during that period is related to voter hedging based on the performance of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Since the DPP is perceived as the guardian of Taiwan identity, when it performs well,

The Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) on May 18 held a rally in Taichung to mark the anniversary of President William Lai’s (賴清德) inauguration on May 20. The title of the rally could be loosely translated to “May 18 recall fraudulent goods” (518退貨ㄌㄨㄚˋ!). Unlike in English, where the terms are the same, “recall” (退貨) in this context refers to product recalls due to damaged, defective or fraudulent merchandise, not the political recalls (罷免) currently dominating the headlines. I attended the rally to determine if the impression was correct that the TPP under party Chairman Huang Kuo-Chang (黃國昌) had little of a

At Computex 2025, Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang (黃仁勳) urged the government to subsidize AI. “All schools in Taiwan must integrate AI into their curricula,” he declared. A few months earlier, he said, “If I were a student today, I’d immediately start using tools like ChatGPT, Gemini Pro and Grok to learn, write and accelerate my thinking.” Huang sees the AI-bullet train leaving the station. And as one of its drivers, he’s worried about youth not getting on board — bad for their careers, and bad for his workforce. As a semiconductor supply-chain powerhouse and AI hub wannabe, Taiwan is seeing