On the opening page of The Cartel, Don Winslow mixes a baby’s cry with the sound of a helicopter’s blades in a predawn raid. That’s reminiscent of his 2005 novel, The Power of the Dog, which also used a baby on its opening page. “The baby is dead in his mother’s arms,” that book began, and went on to describe the horrific image of a bullet-riddled Madonna and child in Mexico. It was the first step into what would become Winslow’s drug war version of The Godfather, with all the grand ambition that implies.

The Cartel is a big, sprawling, ultimately stunning crime tableau that can be read as a stand-alone. But the ideal approach, if you can make the leap and commitment, is to read the two books in sequence as a part one and a part two. Together, the two span nearly 1,200 pages and 40 years and present a multifaceted view of what is, in Winslow’s opinion, America’s longest war: the war on drugs. The Power of the Dog covers the first 30 years, during which the war was fought on a much more intimate scale than it was from 2004 to 2014, the period covered by The Cartel.

Although the two books are filled with equally vicious reality-based events, The Cartel reflects the grim latter-day shift from traditional gangster tactics to those of global terrorism. The new book’s cartels have their own private, monstrously media-savvy armies that reflect the basic thinking of al-Qaeda. As one of Winslow’s characters puts it: “What good is an atrocity if no one knows you did it?”

The Cartel picks up at a relatively easy entrance point in this crowded and complicated story. The first book’s main characters, Art Keller and Adan Barrera, who met young and went on to become a Drug Enforcement Administration agent and a Sonora cartel kingpin, remain sworn enemies. Much of what happened in the first book guarantees that they will stay that way. One, as a private joke, has sworn to himself that he will put poppies on the other’s grave.

As The Cartel begins, Barrera still holds court and runs an empire with a mannerliness that recalls Corleone-style noblesse oblige. But he does it from inside the Metropolitan Correctional Center in San Diego, where, at 50, he faces multiple lifetime sentences. Even the quick synopsis of what Keller did to trick Barrera onto US soil is enough to justify the undying enmity between them. They have no intention of ending their grudge match, just as Barrera has no intention of staying incarcerated for very long. (Certain details, like how the Barrera clan celebrates Christmas in prison, comes from Winslow’s extensive research into real figures in the drug war.)

The Cartel has so many moving parts that there is reason to envy Keller the Christmas he spends all alone, eating a frozen dinner, studying the spreadsheets and background data the book never provides in consolidated form. There are so many murderous grudges and so many shifting gang allegiances that parts of the book require close attention; you may even find yourself backing up a time or two.

What is never confusing, though, is the degree of vengefulness and corruption that has been bred into some of the cartel’s soldiers at shockingly early ages. And since the command of choice here is to inflict pain as frighteningly as possible, there are no scarier words a captive can hear than “you’re next.”

Winslow, a cult favorite for many reasons, has written about a different milieu — California’s surf and drug culture — much more stylishly (The Dawn Patrol) and conversationally (Savages) than he writes here. The Cartel, like The Power of the Dog, can be better appreciated for its gritty, gasp-inducing knowledge of true crime’s brutal extremes, and for its unflinching awareness of what Winslow calls “evil beyond the possibility of redemption.”

Even tougher than the outright violence is the slow destruction of idealists — be they in journalism, medicine, intellectual life, government or just in search of a more lawful Mexican society — who think they can escape the long shadow of this ugliness, and who one after another are proved horribly wrong. The Cartel, which involves graphic beheading and dismembering, is dedicated to a long list of journalists who have been killed or have “disappeared” in the Mexican drug wars.

But there are high spirits and comic relief to be found in the way that much of the drug lords’ and wannabes’ self-images come from US popular culture. Many of the characters seem to think of themselves a la The Godfather, to the point where “Al Pacino” can be used as a verb, however badly. To “Al Pacino him” seems to denote a revenge killing in a restaurant, even if the crucial gun-hidden-in-the-bathroom part is skipped to save time. To become a famous gangster means to have a movie made about you, although one of the most appealingly thickheaded killers here doesn’t understand why he needs to be punished at the story’s end.

Winslow, who has rightly been compared to James Ellroy (and praised by Ellroy) for his ability to capture an entire crime culture in the sweep of The Cartel, leaves room for at least one smart, interesting woman to play the drug lords’ game better than the men do. But as in all great crime fiction, the game is as damning as it is seductive and not conducive to happily-ever-afters. The Cartel culminates in a near-symphonic array of lethal coups de grace, written with such hallucinatory intensity that the whole book seems to have turned into a synchronized fireworks display. And still Winslow adds one last, hellish image that “takes the freakin’ cake.” To make sure this story is something you won’t forget.

Has the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) changed under the leadership of Huang Kuo-chang (黃國昌)? In tone and messaging, it obviously has, but this is largely driven by events over the past year. How much is surface noise, and how much is substance? How differently party founder Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) would have handled these events is impossible to determine because the biggest event was Ko’s own arrest on multiple corruption charges and being jailed incommunicado. To understand the similarities and differences that may be evolving in the Huang era, we must first understand Ko’s TPP. ELECTORAL STRATEGY The party’s strategy under Ko was

Before the recall election drowned out other news, CNN last month became the latest in a long line of media organs to report on abuses of migrant workers in Taiwan’s fishing fleet. After a brief flare of interest, the news media moved on. The migrant worker issues, however, did not. CNN’s stinging title, “Taiwan is held up as a bastion of liberal values. But migrant workers report abuse, injury and death in its fishing industry,” was widely quoted, including by the Fisheries Agency in its response. It obviously hurt. The Fisheries Agency was not slow to convey a classic government

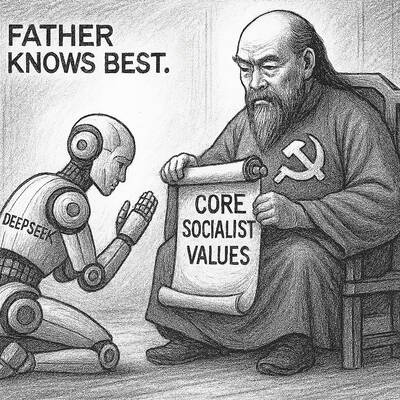

It’s Aug. 8, Father’s Day in Taiwan. I asked a Chinese chatbot a simple question: “How is Father’s Day celebrated in Taiwan and China?” The answer was as ideological as it was unexpected. The AI said Taiwan is “a region” (地區) and “a province of China” (中國的省份). It then adopted the collective pronoun “we” to praise the holiday in the voice of the “Chinese government,” saying Father’s Day aligns with “core socialist values” of the “Chinese nation.” The chatbot was DeepSeek, the fastest growing app ever to reach 100 million users (in seven days!) and one of the world’s most advanced and

It turns out many Americans aren’t great at identifying which personal decisions contribute most to climate change. A study recently published by the National Academy of Sciences found that when asked to rank actions, such as swapping a car that uses gasoline for an electric one, carpooling or reducing food waste, participants weren’t very accurate when assessing how much those actions contributed to climate change, which is caused mostly by the release of greenhouse gases that happen when fuels like gasoline, oil and coal are burned. “People over-assign impact to actually pretty low-impact actions such as recycling, and underestimate the actual carbon