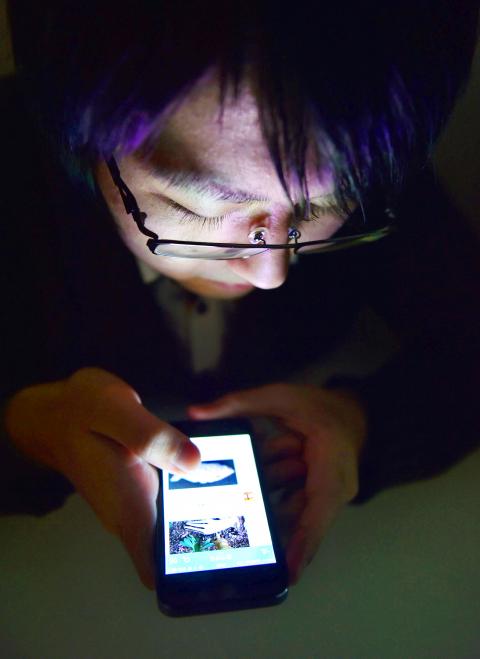

For Japanese teenager Sumire, chatting with friends while she sits in the bath or even on the toilet is nothing out of the ordinary. An ever-present smartphone means she, like much of her generation, is plugged in 24-7 — to the growing concern of health professionals.

“I’m online from the moment I wake up until I go to sleep, whenever I have time — even in class,” the 18-year-old, who gave only her first name, told AFP.

“I’m always messaging friends on Line, even when I’m in the bath. I guess I feel lonely if I’m not online, sort of disconnected,” she said, referring to a Japanese chat app used by about 90 percent of high school students here, according to a recent survey.

Photo: AFP/ Yoshikazu Tsuno

While Sumire acknowledges that she probably uses her iPhone too much, she is far from alone in a country where young people are frequently glued to a screen.

High school girls in Japan spend an average of seven hours a day on their mobile phones, a survey by information security firm Digital Arts revealed this week, with nearly 10 percent of them putting in at least 15 hours.

Boys of the same age average just over four hours mobile phone use a day, the research found.

Photo: AFP/ Kazuhiro Nogi

The problem has become so grave a whole field of medicine has developed to ween them off their digital props.

“This is what we call the conformity type,” psychiatrist and leading net addiction specialist Takashi Sumioka said. “This type of obsession is caused by the fear that they will get left out or bullied in a group if they don’t reply quickly.”

Recent research by the Shanghai Mental Health Center assessing brain scans of youths with technology addiction showed it caused neurological changes similar to those who have alcohol and cocaine dependency.

DIGITAL DETOX

Despite greater awareness of such pitfalls, the potential for digital addiction has multiplied, presenting a growing problem for today’s teenagers — the so-called Generation Z — whose digital immersion started early.

“More people now are addicted to using tablets, rather than (desktop) computers,” psychiatrist Sumioka said. “They no longer need to lock themselves in a room, because they carry smartphones with them. It’s more difficult to see that someone has a problem.”

In a 2013 government survey conducted on some 2,600 young adults, 60 percent of Japanese high school students showed strong signs of digital addiction.

Authorities are now rolling out special technology “fasting” camps to research what can be done to get the plugged-in unhooked. The number of people Sumioka treats for this specific problem at his dedicated technology-addiction facility also tripled between 2007 and 2013.

Sumioka, who treats patients with a therapy called “digital detox”, says many patients arrive almost unable to function without the comforting prop of a smartphone or tablet to connect them to the online world.

His treatment involves repeated vognitive behavioral therapy sessions aimed to alter the way patients think about and respond to technology. He also incrementally limits the time they can spend connected.

“I have them write down daily timetables so that they can see how much they are controlled by smartphone and the Internet,” he added, warning it usually takes at least six months for a recovery.

‘I NEVER LEFT MY ROOM’

In many ways, he says, the new trend of behavior mirrors how Japanese society as a whole works, where the idea of harmony is prized.

“Japan is a society of conformity. This means in other words people do not necessarily have their own opinions but simply go with the flow of the group,” Sumioka said.

Computer teacher and technology addiction counsellor Miki Endo, said she frequently meets people who are more comfortable communicating online than in real life.

She began giving advice after watching a young woman in her class transform when using an online chat forum. “She suddenly became like a different person,” Endo recalled.

“As soon as she got onto a message board, the woman, usually a very quiet person, started talking and laughing to herself.

“She seemed to forget that I was there, and didn’t notice I was talking to her.”

It is clear technology addiction has evolved — less than a decade ago those afflicted were mainly ‘gamers’ who locked themselves away to play on their consoles.

As an 11-year-old, Masaki Shiratori spent up to 20 hours a day battling the monsters that roamed the landscapes of “Arado Senki”, a game known in English as “Dungeon Fighter Online”.

“I never left my room except for the times I used the bathroom,” he said.

The change came at 14, when his parents put him in a special hospital, cutting all access to the game as doctors helped him break his addiction.

Shiratori, now 20, has a much healthier relationship with screens. He is studying computer science at a university near Tokyo, and wants one day to be able to make a living out of it.

“This is the only thing I am better at than other people,” he said.

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 28 to May 4 During the Japanese colonial era, a city’s “first” high school typically served Japanese students, while Taiwanese attended the “second” high school. Only in Taichung was this reversed. That’s because when Taichung First High School opened its doors on May 1, 1915 to serve Taiwanese students who were previously barred from secondary education, it was the only high school in town. Former principal Hideo Azukisawa threatened to quit when the government in 1922 attempted to transfer the “first” designation to a new local high school for Japanese students, leading to this unusual situation. Prior to the Taichung First

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

The Ministry of Education last month proposed a nationwide ban on mobile devices in schools, aiming to curb concerns over student phone addiction. Under the revised regulation, which will take effect in August, teachers and schools will be required to collect mobile devices — including phones, laptops and wearables devices — for safekeeping during school hours, unless they are being used for educational purposes. For Chang Fong-ching (張鳳琴), the ban will have a positive impact. “It’s a good move,” says the professor in the department of