I once stood naked in an Amsterdam art gallery painted entirely blue. Against my genitals I held a large and sharp-looking knife, and round my feet lay some 50 oranges. This was called “performance art” and I never made a cent out of it, though I think someone paid for the oranges. How such people later became book reviewers is part of the history of a generation, and unlikely to be repeated.

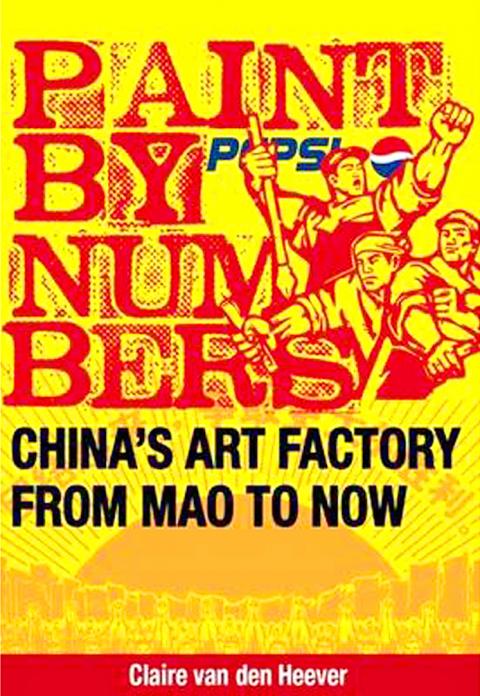

But plenty of artists, in China and elsewhere, have made large amounts of money from such innocent pranks. They’re now a category of “contemporary art,” in other words anything the creator cares to call art other than painting pictures on a canvas. The history of such things in China is the subject of this new book, Paint by Numbers. The author, Claire van den Heever, is a native of South Africa who has traveled extensively in Asia and has a Web site of her travel pieces at www.oldworldwandering.com. Having mastered Mandarin Chinese while living in Shanghai, she interviewed 15 prominent artists working in contemporary styles, did a lot of other research, and then produced this readable and very useful book.

Contemporary art is hard to define. Indeed, the desire to elude definition is arguably one of its motivations. Is it mostly play — in other words, a series of games? Or does it seriously claim to be evaluated alongside the masterpieces produced by traditional painters? Things may change, but the view that it is comparable is certainly dominant at present.

Needless to say, such art was and is the result of Western influences entering the country. That Asia should emulate and copy the West has been true in many spheres. There has, it’s true, been an opposite influence, of Asia on Europe in artistic matters, as the effect of Japanese art on Van Gogh shows. But the twin trends of industrialism and modernization have seen to it that the dominant trend has been in the opposite direction.

WESTERN INFLUENCE

China, however, has been at pains to lessen the influence of what its government considers Western art’s “decadent” elements, and contemporary art, with its installations and performance art — wrapping part of the Great Wall in bandages or sitting in a toilet covered in honey — has been seen as a product of this decadence. Since the 1980s periods of relative freedom and ones of stricter control have tended to alternate. High-profile foreign sales initially led to official relaxation, encouraging the artists to take greater liberties, resulting in turn in a harsher clamp-down.

A big step forward, the New Wave Art Movement, began in 1985 and involved more than 2,000 artists. The famous China/Avant-garde exhibition opened in Beijing in February 1989. Then Tiananmen Square happened, and China’s progressive artists essentially went into hiding.

Foreign interest in China’s contemporary art scene grew, however, in 1993 with another China/Avant-garde exhibition, this time a show that toured for four months in northern Europe. And soon afterwards the economy in China took off. With the new prosperity, though, ironies abounded. “Artists were criticizing society’s consumerism,” Van den Heever writes, “while their own works became luxury goods.”

This book may not be the work of a major critic, but it’s certainly a comprehensive overview by an intelligent and hard-working observer of the art scene in China.

Chinese contemporary art, according to Van den Heever, made its first big impression on the international art scene in 2006 when Sotheby’s in New York held their first auction of contemporary Asian art. It made over US$13 million, as opposed to the estimate of US$8 million. There was then a relapse following the financial crisis in 2008. But the market quickly bounced back, and a sale of part of Belgian collector Guy Ullens’ private hoard of early contemporary art from China in Hong Kong in 2011 reached new heights, with a triptych by Zhang Xiaogang (張曉剛) going to an anonymous bidder for US$10.1 million.

Another foreign collector was the Swiss ambassador to Beijing, Uli Sigg. “Chinese contemporary art would look very different were it not for him,” said artist Zhou Tiehai (周鐵海), who bought a large Beijing house on the proceeds of sales to Sigg.

ARTIST COMMUNES

Artists’ communities, such as Yuanmingyuan and Beijing East Village, also feature in the book, as do performance art feats such as Zhang Huan’s (張洹) 65KG in which he hung upside down, naked and in chains, while his blood dripped through tubes to sizzle on a hotplate below. Also featured is the provocative performance art of Ma Liuming (馬六明) who, as well as having representations of his face fixed onto plastic dolls, often poses naked or dressed as a woman. (Why nudity is so often a feature of these events is anyone’s guess). Such performances, of course, are hardly collectible, but other products are, and demand for them isn’t only international, as nowadays the new Chinese middle-class is keen to acquire them as well.

The book ends with an interview with Ai Weiwei (艾未未), which the author says took her 50 e-mails to arrange. When she eventually arrived she became caught up with a team from CNN, and Ai didn’t even realize he had an appointment with her.

The author later writes that the future for Chinese art can look bleak. “If maintaining ‘social harmony’ is a priority,” she writes, “then expression of any sort cannot be allowed to exist unguided.” But fame and wealth also make their impression in China, she adds, meaning that any artist who’s successful enough in the international market might well be afforded official recognition eventually. But what is the real significance of huge sale prices when these sales are to investors rather than art-lovers like Ullens, she asks. Ullens himself has significantly now turned his attention to acquiring the work, not of emerging Chinese artists, but of emerging Indian ones.

The author ends on a more positive note, concluding that avant-garde art is risk-taking by nature, and that artists willing to take such risks are sure to emerge again in the future. Let’s hope so. They may not exactly deserve their wealth, but at least they aren’t arms dealers.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the