A small group of American pilots that defeated much superior Japanese forces in the skies over China and Burma during World War II became a symbol of America’s military might and were beloved by the people in war-ravaged China.

The legend of US commander Claire Lee Chennault and his fighting force known as the Flying Tigers is being revived in The Flying Tigers (飛虎傳奇), a four-part documentary television series initiated as a commemorative effort to mark the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II.

A co-production by Taiwan’s Public Television Service (PTS, 公共電視台), LIC China, a documentary production group based in Beijing, and DocuChina of Shanghai, the film examines the life of Chennault and the history of the storied Flying Tigers through archival footage, historical photographs, interviews and digitally rendered aerial combat.

Photo courtesy of Public Television Service

While straightforward in its chronological narrative, the documentary, which covers the period from 1937 to 1945, has strong dramatic elements as it shows the maverick side of Chennault’s personality.

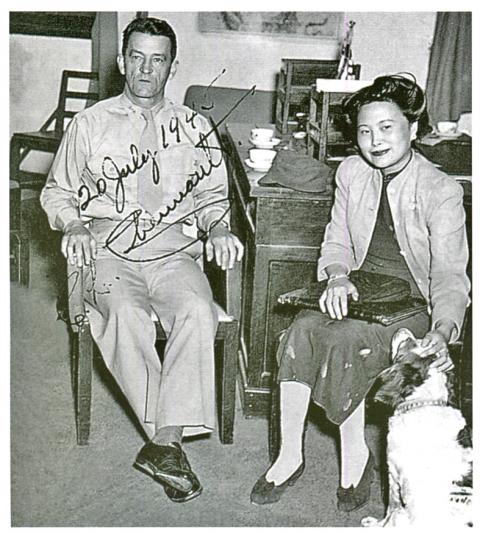

CHENNAULT IN CHINA

The film begins in 1937 after Chennault was forced to retire from the US Army, mostly because his military tactics went against those advocated by the US Army Air Corps. Soon, the dissenter found a good chance to prove himself in China when he was recruited as an adviser for the Chinese Air Force and quickly became a favorite of Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) and his US-educated wife Soong Mei-ling (宋美齡).

Photo courtesy of Public Television Service

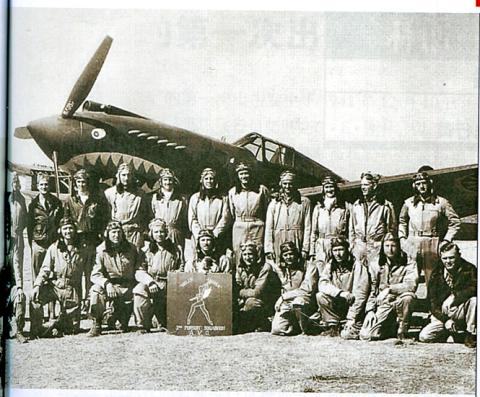

Despite opposition from the US Army, Chennault and his Chinese allies successfully convinced Washington in 1940 to give China planes and pilots to withstand Japanese bombing campaigns. A year later, a group of young Americans arrived in Burma, then a British colony, from San Francisco. They became members of the American Volunteer Group (AVG) under the command of Chennault. Many of the recruits hadn’t been trained as fighter pilots. Some crashed their planes during training, resulting in a number of deaths.

“Many didn’t know what they were getting themselves into,” Chuck Baisden says in the film. Baisden was among the first Flying Tigers to arrive in Burma and worked as an armorer at Hell’s Angels, one of the three squadrons that formed the AVG.

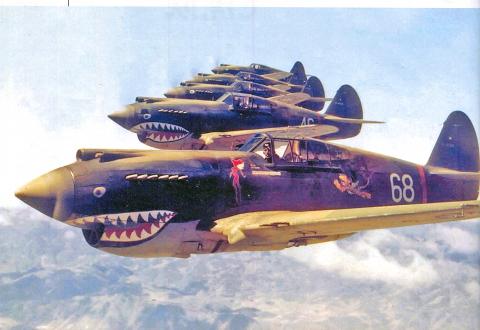

It soon became apparent that Chennault’s unconventional tactics worked. The AVG fighter pilots, who flew the single propeller-driven P-40 fighter with a grinning shark’s mouth painted on its nose cone, started to defeat the previously invincible Japanese planes.

Photo courtesy of Public Television Service

The AVG fought on until July 1942, when it was formally incorporated into the US Army. Chennault had rejoined the Army with the rank of colonel, commanding the Fourteenth Air Force, which the Chinese still referred to as the Flying Tigers.

Interviews with surviving Flying Tigers brings to life the difficulties faced by the recruits. Former AVG armorer Joseph Poshefko, for example, recalls how they fought the seemingly impossible combat amid chronic equipment and ammunition shortages.

“As young, adventurous, dedicated boys, we did the best we could with what we had. They [The Japanese] didn’t give up. We didn’t give up.” Poshefko says.

Photo courtesy of Public Television Service

Others tell of the extremely dangerous flights across the Hump, referring to the part of the Himalayan Mountains over which they flew transport planes to deliver military supplies from India to China. It was the only way to resupply Chinese troops.

“It was an ongoing meteorological situation where warm, damp air came up and turned into thunder storms. Thunder storms are extremely hazardous. If a plane gets caught in it, no matter the size, it can be torn apart,” pilot Wilber Maxwell says.

With each plane carrying only three to five tons of supplies at a time, the Hump pilots flew their missions 24 hours a day, seven days a week, regardless of the weather.

Photo courtesy of Public Television Service

“There was a general who decided that there was no weather too bad for flying, so we flew,” Wilber says.

The airlift lasted for three and half years, during which time some 600 planes crashed when flying across the Hump. More than 1,700 lives were lost.

By 1945, the allied forces succeeded in chasing Japanese planes out of China’s skies. At the same time, Chennault continued to fight a losing battle with his own superiors, American ground commander General Joseph Stilwell, and, later, air force commander H H Arnold. He was again forcibly sent into retirement in 1945, only a few weeks before Japan surrendered.

AFTER THE WAR

A coda to the story sees Chennault retuning to China to build an airline that transported supplies, equipment and personnel. The airline was closely linked to Office of Strategic Services, a wartime intelligence agency and a predecessor of the Central Intelligence Agency, helping to conduct espionage operations for the US in the Cold War that followed. But that is another story.

The four-installment series will air on PTS HD channel at 4pm every Saturday starting this week. More information can be obtained at www.pts.org.tw/theflyingtigers.

May 26 to June 1 When the Qing Dynasty first took control over many parts of Taiwan in 1684, it roughly continued the Kingdom of Tungning’s administrative borders (see below), setting up one prefecture and three counties. The actual area of control covered today’s Chiayi, Tainan and Kaohsiung. The administrative center was in Taiwan Prefecture, in today’s Tainan. But as Han settlement expanded and due to rebellions and other international incidents, the administrative units became more complex. By the time Taiwan became a province of the Qing in 1887, there were three prefectures, eleven counties, three subprefectures and one directly-administered prefecture, with

It’s an enormous dome of colorful glass, something between the Sistine Chapel and a Marc Chagall fresco. And yet, it’s just a subway station. Formosa Boulevard is the heart of Kaohsiung’s mass transit system. In metro terms, it’s modest: the only transfer station in a network with just two lines. But it’s a landmark nonetheless: a civic space that serves as much more than a point of transit. On a hot Sunday, the corridors and vast halls are filled with a market selling everything from second-hand clothes to toys and house decorations. It’s just one of the many events the station hosts,

Among Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) villages, a certain rivalry exists between Arunothai, the largest of these villages, and Mae Salong, which is currently the most prosperous. Historically, the rivalry stems from a split in KMT military factions in the early 1960s, which divided command and opium territories after Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) cut off open support in 1961 due to international pressure (see part two, “The KMT opium lords of the Golden Triangle,” on May 20). But today this rivalry manifests as a different kind of split, with Arunothai leading a pro-China faction and Mae Salong staunchly aligned to Taiwan.

Two moves show Taichung Mayor Lu Shiow-yen (盧秀燕) is gunning for Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) party chair and the 2028 presidential election. Technically, these are not yet “officially” official, but by the rules of Taiwan politics, she is now on the dance floor. Earlier this month Lu confirmed in an interview in Japan’s Nikkei that she was considering running for KMT chair. This is not new news, but according to reports from her camp she previously was still considering the case for and against running. By choosing a respected, international news outlet, she declared it to the world. While the outside world