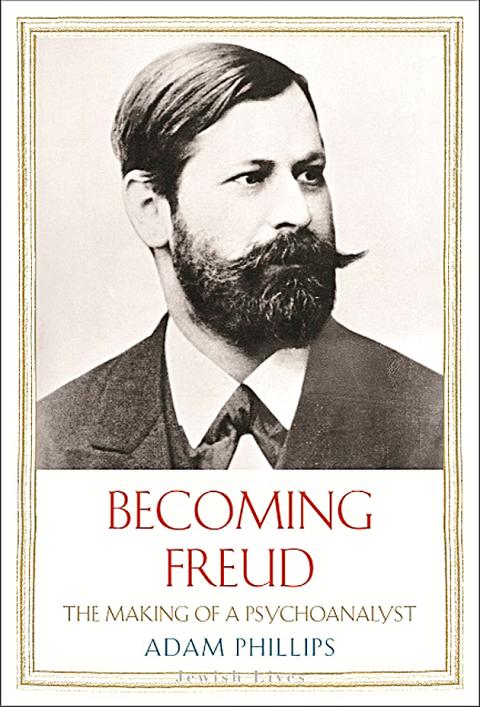

Becoming Freud: The Making of a Psychoanalyst, by the English psychoanalyst, editor and writer Adam Phillips, is about the first 50 years of Freud’s 83-year life. This short, dense book is partly a group of abbreviated biographical commentaries, partly about Freud’s career and writings until 1906. It uses both ordinary language and literary terminology to replace traditional psychoanalytic terms and jargon, although Phillips’ understanding and theorizing are familiar and generally conformable. It is also a less-than-perfect performance.

There is almost nothing in Freud’s work that is not contradicted somewhere else in it. As a writer, Phillips specializes in paradoxes and antitheses — almost all of which he puts forth thoughtfully and gracefully. One of Freud’s large contradictions has to do with biography itself. On various occasions, Freud expressed his skepticism and dislike of, and distrust and general disbelief in, the truth of biography. Phillips implies that the complexities of psychoanalytic experience would be “Freud’s proof that biography is the worst kind of fiction,” but he produces no evidence to support this assertion. And readers of this compact study would not be entirely mistaken if they described it as, in large degree, an unapologetic biographical study.

Freud himself went on to become a biographical writer of exceptional note. His case histories are all biographical accounts of considerable intricacy. And still later, he wrote extended biographical studies of figures like Michelangelo and Moses. Phillips is silent on this apparently puzzling matter.

Freud didn’t begin by writing stories or exercising his inventiveness with language. Phillips faithfully traces his movement from materialistic and positivist science and research into clinical medicine and neurology, and from there into the interpersonal study of hysteria and other neurotic disorders.

Phillips follows this development by trenchantly reviewing Freud’s relations with four men: Ernst Brucke, the great materialistic laboratory scientist; Jean-Martin Charcot, the charismatic wizard of hypnotized hysteria in Paris; Josef Breuer, Freud’s senior Viennese colleague who had the patience to attend to the storms of unhappiness of a severely hysterical young woman; and Wilhelm Fliess, a brilliant crackpot whom Freud called his “daimon” (a personal/impersonal force) and who stimulated him to confront and organize some of his as yet ungrounded insights and speculations.

Out of these and other influences, and from the depths of the beginning of Freud’s own self-analysis, there emerged the first organized phase of his great genius and productivity. Five publications from 1900 to 1905 formed the foundation of psychoanalysis — the magisterial The Interpretation of Dreams (1900) and the works that followed, partly as virtual commentaries, addenda, extensions and epilogues: The Psychopathology of Everyday Life; Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality; Fragment of an Analysis of a Case of Hysteria; and Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious. Phillips does not have the space to discuss any of these texts, but he drops shrewd comments as he proceeds.

Much the same holds true for Freud’s family and personal life. Phillips has virtually nothing to say about Freud’s mother, or his wife or children (except for a couple of comments on Anna). He skips through Freud’s childhood, except for some attention paid to Freud’s father and his pre-Viennese and Moravian life. Freud was, of course, born a Jew, though he retained absolutely no religious belief throughout his life. Nevertheless, he remained acutely attentive to his Jewish identity and situation as a semi-foreigner and sociocultural alien in Vienna, from the later Victorian and prewar years to his fleeing from the Nazis in 1938.

Phillips makes brief remarks about Freud’s Jewishness, which he more or less repeats here and there, but offers no central set of interesting comments about it. (This book is part of the Jewish Lives series from Yale University Press.) On the other hand, he spends four solid pages describing the Dreyfus case, a great European matter on which Freud had almost nothing to say. This striking imbalance is what the old psychoanalysts called a displacement and does damage to the structure of Phillips’ survey.

Similar reservations apply to some of Phillips’ strategic uses of language. He avoids many of Freud’s formulations, and thoroughly bypasses the technical language of the psychoanalytic movement, most particularly the jargon of American ego and narcissistic psychology. This is what you expect from a gifted literary spirit, and on the whole is very refreshing.

Then there is Phillips’ view that in psychoanalysis, the patient is altered from a suffering victim or supplicant to an individual who is “self-fashioning.” I have yet to meet someone who has been psychoanalyzed who uses such a term to describe the struggling, painful, embarrassing and often boring and frustrating experience of an analysis. Self-fashioning, like “liberation,” is pretty much a literary flourish.

Finally, there is sex. Phillips’ favorite term for it, in general, is “sociability.” It would take paragraphs to describe the weakness and inadequacy of this term. But to put it shortly and for adults, it simply takes much of the sex out of sex — it is disembodied and mostly talk.

Phillips’ general view of Freud is of a mind that focuses on language and stories and not of someone who, for most of his life, dealt with the emotional suffering and physical incapacities of others.

Still, these are minor flaws in an intelligent and well-written book. One question remains: For whom has it been written? This is certainly not an introduction to Freud and his work. Nor is it for practicing professionals. It seems composed, implicitly, for advanced or graduate students and their like in the humanities. Many of them have read bits of Freud, many have learned about Freud through secondary texts, and many have become acquainted with him through Freud’s recent French admirers. If they read Phillips’ compact book, they will discover for themselves many useful correctives to current views.

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,